A Market Failure or Successful Social Experiment: Re-Examining the Chinese Adaptation of Dutch Reality TV Utopia

Lisa lin / Anglia Ruskin University

A farmer, a shoemaker, a personal business owner, a tour guide, a fitness instructor, a university student, a rural migrant worker, a military veteran, a doctorate candidate of psychology, a vagrant, a boxer, a craftsman, a fashion designer, a retired accountant of a state-owned company and a rock singer.

Tencent Video, 2016

On June 23, 2015, 15 ordinary Chinese citizens from different classes and professions started a new life together on a remote barren plateau in Tonglu County (China) for one year with the aim of building a new (ideal) society from scratch using two cows, ten chickens and ¥50,000 (US$7,960). A ground-breaking social experiment, We15 is a 24-hour live streaming reality show on Tencent Video from June 2015 to June 2016. Whether to solve the agenda of the communal life via democracy, dictatorship or legislature is a valuable experience for both residents as well as audiences in a one-party state. The 24-hour live streaming of We15 created a sense of authenticity and companionship among online users, who lived concurrently with the residents ‘under the dome’ by switching on live camera feeds on their internet browsers anytime to observe the happenings on an isolated mountain. However valuable the social experiment was, this £23-million-budget series was cancelled after the first season, whereas its Dutch counterpart ran uninterrupted for four-and-a-half years until the lease of the residency site could not be extended.

Whereas a project may have been considered as a market failure, it can be a critical success from cultural, political and aesthetic perspectives. This article uses We15 (Tencent Video, 2015-2016) – a Chinese adaptation of Dutch TV format Utopia (licensed by Talpa) – as a case study to examine how failed projects can be critically successful and how media failures can be defined and reconsidered. By doing so, I hope to illuminate how failure can be viewed as a multi-faceted process that operates outside of a failure-versus-success model on cultural, political, economic, and aesthetic levels. The Oxford English Dictionary (2021) defines a failure as ‘a thing or person that proves unsuccessful’, and in this sense, how we define success can overturn what is deemed as a failure. Drawing upon my ethnographic fieldwork data on convergent Chinese television industries between 2016 and 2017,[1] I will examine how the Chinese adaptation of Utopia – though deemed as a market failure – serves as a valuable social experiment by aspiring Chinese producers who embrace the creative potential empowered by the commercially-run platform model and integrated internet services in the one-party state.

Created by Dutch media tycoon John de Mol in 2014, the reality format Utopia is based on Sir Thomas More’s 1516 book Utopia (derived from the Greek word ou-topos (no place/nowhere) and combined with eu-topos (good place). As an ambitious social experiment, Utopia asked fundamental questions about society and democracy: “Are people able to create an ideal society from scratch? Will it be ultimate happiness or complete chaos?”, according to John de Mol. Following the success of Dutch production, the reality format was subsequently adapted in five countries (the USA, Canada, Turkey, Germany, and China) (see Figures 1-2). As a ground-breaking television experiment with a visionary approach to life, Utopia gives fifteen individuals a chance to leave their daily lives and explore the possibility of building a better society and creating what they believe is an ideal civilization over the course of a year in the absence of contemporary laws and rules.[2]

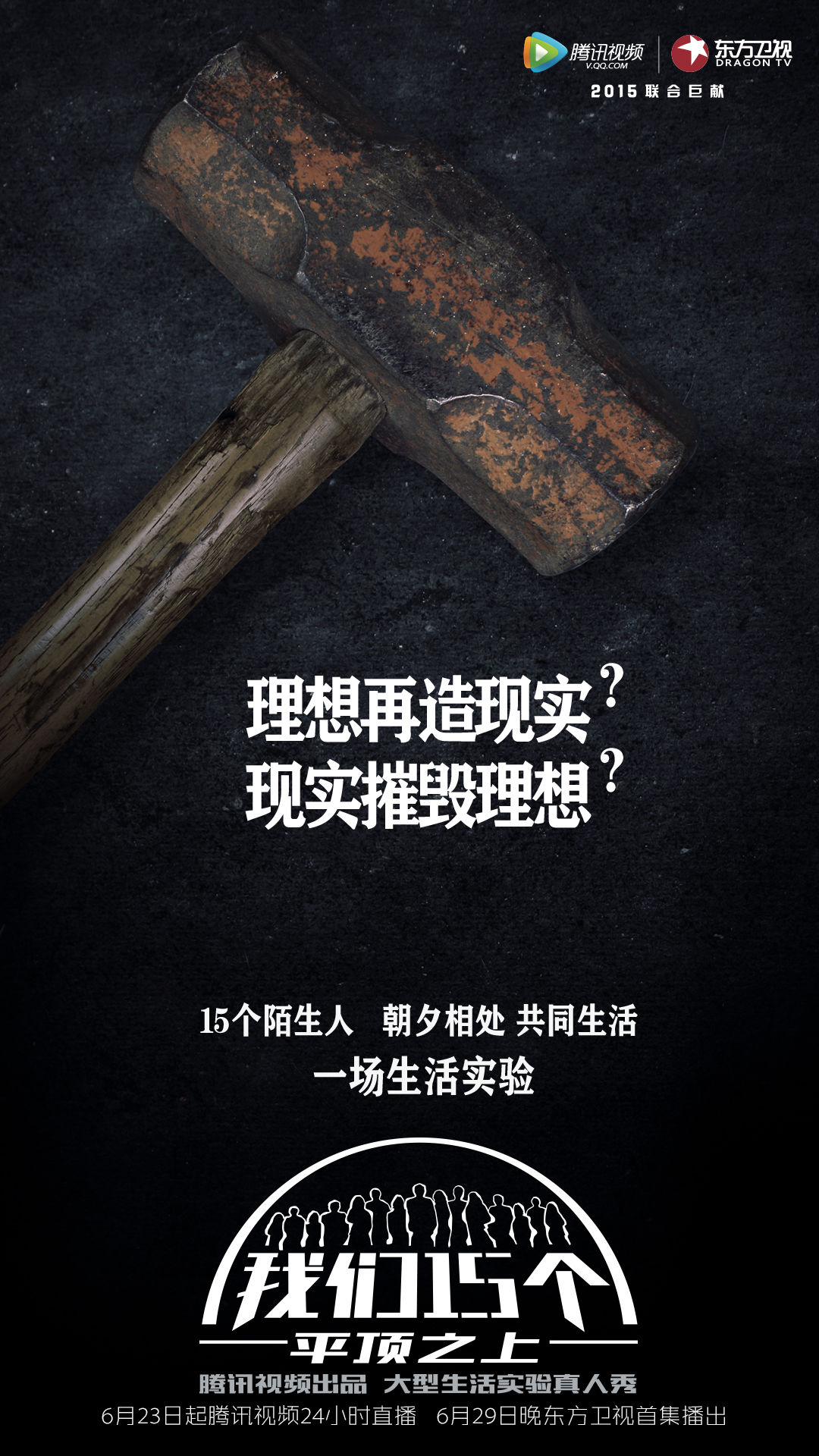

With the tagline “a social experiment with 15 strangers living together every day and night,” the online poster poses a bold question: “Idealists create reality, or reality destroys idealists” (see Figure 3). Instead of selecting celebrity-driven narratives in most Chinese reality television, ordinary citizens from various classes, cultures and communities were selected as participants for this utopian/anarchist social experiment (see Figures 4-5): how would decision-making be organised in the community’s life? Through democracy or socialist-style commune? The residents represent a transitional Chinese society, from intellectuals to farmers, from state enterprise employees to private merchandisers, which together could be interpreted as Chinese media producers’ process of working through the complex issues in contemporary Chinese society, one comprised of seemingly contradictory forces of communism, socialism and capitalism.[3]

The premise of the show – ‘Let us start from the beginning and go back to the essence of life’ – functioned as both an internal production creed as well as an outward-facing promotional slogan that spoke to the audiences and the industry (see Figure 6). Liveness is twinned with authenticity.[4]

As the executive producer of We15 argues:

The philosophy of this show is minimising interference with the residents. It is, so far, the most realistic ‘reality TV’ (in China). We have truly little script for the production. Whether audiences like one of them or not, it does not matter a lot. We are having one social experiment on the mountain.

Author’s Interview, 17/10/2016, Beijing

The quote shows the editorial direction towards authenticity and realism during the production with minimal interference and commercial pressure. The format of the 24h live streaming facilitates Chinese producers to exercise their creative freedoms within certain boundaries, working through difficult political and creative terrain in non-fictional genres.

Though critically acclaimed as a valuable social experiment (e.g. 1.16 million views on the online program discussion page at Zhihu.com and 1.13 million posts on Chinese online forum Baidu Tieba),[5] We15 was viewed as a failure by both Tencent Video executives and industry practitioners for both strategic and economic reasons which led to the cancellation of the commissioning of forthcoming seasons in 2016. Industrial and regulatory systems in China have compromised the ambitious visions of Chinese media producers. Both strict censorships and an ‘amusing-to-death’ media environment have failed the producers’ cultural aspiration and idealism in the social experiment of We15. In an environment where ‘public was oppressed by their addiction to amusement’ as Neil Postman argued in 1985,[6] audiences who were looking for dramatic tension and celebrity appearance often found the show unattractive and sometimes unwatchable. The failure of real-life skills (such as the participants’ poor skills and idleness at making a living) resulted in a society of chaotic scarcity rather than an admirable utopian society in the Chinese adaptation, which also contributed to the cancellation of the series. Similarly, though Fox’s adaptation of Utopia was cancelled shortly after 13 episodes in less than two months, ‘we need more failures like Utopia’ as American media critics argue.[7]

Having considered the political metaphor ‘Utopia’, the production team had decided to change the title from Utopia to We15 which had less political symbolism (Fieldwork Data, 2016). For the development producer, the political influence has been tremendous:

Any localisation of the programme must face huge challenges. The concept of We15 is very ahead of time, which is a very typical Northern-European format with advanced ideology. We are subject to regulation policies and ideological obedience

Author’s Interview, 02/11/2016, Beijing

This strategy indicates the delicate balancing act that producers tread between ‘self-censorship’ and creative practices in their daily practices, where decisions might ostensibly be motivated by fears.

The ubiquity of media censorship also poses huge challenges for real-time content censorship during the live streaming of We15. Failure to adhere to media regulations and ideological policies could not only lead to a ‘fatal ban’ the on the transmission that would undermine the economic performance of companies but also terminate one’s media career. In addition to the compliance process in Western versions to filter sexual and violent content, the Chinese production team introduced a five-minute transmission delay to filter any politically-inappropriate conversations and scenes. A team of live streaming compliance was assembled to monitor the 24/7 live streaming feeds and replace ‘inappropriate’ pictures/languages with empty shots of cows, chicken and landscapes. The empty shots were widely complained by online viewers who found the cutaways disruptive and distractive for the viewing process, jokingly termed the empty shots as ‘being harmonised by the government’ (Fieldwork Data, 2016). Despite the range of bitter and sweet challenges, the production team at Tencent Video expressed a strong sense of achievement and passions for the Chinese adaptation of Utopia.

In a nutshell, We15 can be viewed as a successful attempt for Chinese media professionals to reflect on the current socio-political system of the one-party state and explore an alternative democratic system in an entertainment-disguised programme. We15 is not only a social experiment per se but also an editorial experiment by Tencent executives and producers wishing to explore the socio-cultural impact and creative potentials of online platforms. The online portal and live streaming technologies have created an alternative space for creative and critical expression that would not be possible on Chinese broadcast channels. This ground-breaking television experiment provides a space for Chinese citizens to develop a miniature social system through voting systems which is absent in contemporary Chinese society. We15 has arguably provoked an increasing number of citizens and media professionals to doubt the promise of the Chinese communist party and explore the potential to create an ideal democratic society with equality and freedoms of expression. We15 epitomises a new wave of creative freedoms and personal expression on Chinese SVOD commissions. The live streaming show forges a public space for intellectual critiques and reflection on the meanings of democracy, utopianism and socialism on the barren mountain.

Image Credits:

- We15 Online Poster (with the tagline ’a social experiment with 15 strangers living together every day and night’) (author’s screengrab)

- Filming Base in the US adaptation of Utopia (author’s screengrab)

- Utopia Logo Plate at the Filming Base in the US adaptation of Utopia (author’s screengrab)

- We15 Online Poster: fifteen strangers standing together on the barren mountain with the programme title We15: Under the Dome (author’s screengrab, Tencent Video, 2016)

- Front Gate of the Filming Base of We15 (author’s screengrab)

- Group Photo of Fifteen Chinese Villagers Seated Around a Campfire (author’s screengrab, We15, 2016)

- Lin, Lisa (2022) Convergent Chinese Television Industries: An Ethnography of Chinese Production Cultures. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/book/9783030917555. [↩]

- Andreeva, Nellie (2014) ‘John De Mol’s Social Experiment Reality Series ‘Utopia’ Lands At Fox,’ Deadline, January 23rd. Available at: https://deadline.com/2014/01/john-de-mols-social-experiment-reality-series-utopia-lands-at-fox-670243/ [accessed Jan 12th, 2022]. [↩]

- For instance, one of the residents Shouwang Zhang, who is a Beijing-based indie rock singer, has been among the rebellious generation of Beijing underground rock music. [↩]

- Ellis, John (2000) Seeing Things: Television in the Age of Uncertainty. London: I. B. Tauris. [↩]

- Zhihu (2022) ‘How Can We Evaluate Tencent Reality Show We15? 如何评价腾讯的真人秀节目《我们 15 个》’ Available at: https://www.zhihu.com/question/27001579 [accessed Jan 10th, 2022]. [↩]

- Portman, Neil (1985) Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Methuen, UK: Viking Penguin. [↩]

- Dehnart, Andy (2014) ‘Why Utopia did not fail despite being cancelled’, Reality Blurred, November 3rd. Available at: https://www.realityblurred.com/realitytv/2014/11/utopia-cancelled-did-not-fail/ [accessed Jan 12th, 2022]. [↩]