Genres Fall Apart—Affective Combustion in the Belly of the Beast

Maggie Hennefeld / University of Minnesota

My favorite movies all depict the apocalyptic but lighthearted explosion of the physical and visible world. A housemaid spontaneously combusts as a gesture of her domestic defiance, a rebellious tomboy floods the house to sail her toy boat indoors and then electrocutes the local police force, or a young woman bulldozes her family’s inherited wealth in a rampage to locate her missing ball of wool. Naturally, my preference for the catharsis of absurdist apocalypse has led me to early silent cinema, where bodies ignite and inanimate objects spring to life as experimental effects of a catastrophically shape-shifting world shot through with unlikely political hope. This is exactly what makes popular culture both indirectly consequential and intellectually exhilarating: its leaky pipeline between material reality and unstable social aesthetics, which reveals itself in the visible excesses, grotesque mutations, and bizarre contradictions endemic to otherwise effortlessly enjoyable media entertainment.

This article is not about silent cinema or the aesthetic politics of industrial modernism, but the current conjuncture—our hellscape of rising authoritarianism, failing democratic institutions (“blah blah blah,” to quote the wise Greta Thunberg), pandemic racism, pandemic Covid, and climate apartheid. Amid this prolonged nightmare of slow-burn rupture with the past and partial awakening to the near midnight of the future, where do we see the structural realities materialize in popular media culture? I do not pose this question on the level of content, such as didactic allegories about climate change or direct thematizations of end-of-the-world malaise à la Bird Box (Susanne Bier, 2018), A Quiet Place (John Krasinski, 2018), or Hulu’s adaptation of Snowpiercer (2020- ). Symbolic recognition is always a red herring in that it can never pierce the veil or deflect the wily excuses of the volatile unconscious—at best, it’s signal boosting, at worst culture war cannon fodder. I am thinking about narrative form, texture, and style: what forbidden possibilities or unthought ideas can sneak past the shaky guardrails of broken conventions? Above all, I am interested in the ramifications for genre.

Media genres today, to put it mildly, are a total mess! But that’s what makes them exciting. For example, in the movie Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, South Korea, 2019), the genre itself falls apart almost two hours into the film, when a cake-in-the-face gag and knife-in-the-heart stab concretize the formal collision of conventional modes: slapstick comedy and slasher horror. A woman quite literally throws a cake in her killer’s face by accident in the very process of being murdered by him. The location of the crime is a child’s birthday party, which turns into a reactivated primal scene for repressed nightmare and homicidal trauma, further dislodging the film’s happy-go-lucky trajectory from a farcical buddy comedy (about crafty hucksters who fail up) to an existential thriller about the atrocities of unmitigated capitalism. The slapstick/horror encounter opens the floodgates of extreme weather catastrophe and its unending misery for racially, socially, and economically minoritized people and communities.

Parasite is a paradigm of abject genre collapse as the detonation device for affective combustion. The latter arises when genres no longer provide discrete containers for cathartic emotions but actively solicit the messiness of mixed feelings (play and mourning, anger and despair, creativity and anxiety) to overspill their distance from materialist class conflict. It is no wonder that Parasite was such a global sensation, the first East Asian film to win a Best Picture Oscar and a top-grossing Blockbuster despite its explicit critique of class inequality, racial biopolitics, and human-made climate disaster. The film touched a nerve.

Lauren Berlant (1957-2021) associates genre rupture (or “genre flailing”) with the cracks and fissures in the smooth surface of “cruel optimism.” Optimism—as the habitual attachment to a potentially promising object—turns cruel, according to Berlant, when it compels our adherence to aims that actively prevent us from flourishing. Pick your poison: gas-guzzling air travel, carbon-spewing movie marathons, methane-flatulating cow meats, or the gamut of shattered occupations ruthlessly defunded by neoliberal austerity—from stable employment to affordable higher education as plausible gateways to upward socioeconomic mobility. Berlant approaches genre convention as a kind of stockbroker between ordinary fantasy and vital possibility. In other words, genre powers the fusion that allows fantasy to melt into reality. TV sitcoms, for example, celebrate the spectacle of episodic normalcy, reassuring family-oriented viewers that somehow all the little moments will finally add up. If comedic “cruel optimism” thrives in the realm of the episodic (whereby all calamity is impermanent and easily reversible), melodrama traffics in the bad timing of continuous seriality. That one is doomed to be always already too late—to stop the murder, save the child, redeem the mother, prevent the bad marriage, and so forth—provides emotional nourishment for viewers to digest larger, immovable structures of social injustice. If comedy holds out hope that nonsense can be consequential, melodrama reassures us that exhaustive seriousness will likewise be futile. Take it easy, you worrywart!

Therefore, what is truly disruptive is not the revival of genre but its wild implosion, particularly in the encounter between episodic ordinariness and serialized suffering. Situation tragedy, humorless comedy, slapstick of survival, and crisis ordinariness are several among the many, exquisite genre-compounds devised by Berlant. They give trouble to the big lie of cruel optimism: that it’s always better to look away than to risk a separation from one’s most perpetual objects. What is the non-substitutable ordinary loss (i.e., habitual, repetitive, even addicting—but not yet at the threshold of mourning or melancholia) without which everything else about YOU (your subject position, object orientation, and relational sovereignty) would all come crashing down? Everything else would combust around the permanent disappearance of that thing. This is precisely how social movements intervene on the level of affect, argues Berlant, by demanding more open and less rigid forms of commitment and belonging to pave the way toward “a new, revolutionary sensorium” (The Female Complaint, 261).

Like many, I have been mourning the too-early/untimely death of Berlant, whose incisively playful writings about feminism, affect, and politics continue to inspire hope in the relevance of hard-fought critical reading to overcome the impenetrable doom of the unraveling conjuncture. What can the messiness of genre mutation offer toward making the aesthetic politics of popular culture less cruel? As a silent film buff, I am always struck by the withering of collective hope from the experience of anarchic slapstick, which even the notorious killjoy T.W. Adorno once described as utopian in its projection of “incessant and spontaneous change” (60). For Walter Benjamin, violent cartoons and live-action slapstick actively held the line between shock-addled alienation and the rise of fascist politics. Even if culture does not instrumentally change the world, it crucially mediates the dangerous whiplash from class exploitation and environmental wreckage. Or, as I learned in my undergraduate Holocaust studies course, things can always get worse.

By way of offering something tangible, I am interested in the recent wave of genre mutant films and television shows. For example, I watched Kevin Can F**K Himself (AMC, 2021- ) with vivid attention, not because it is an especially brilliant text, but because its genre trouble appeals to my convictions about what could yet arise when isolated forms are brought to bear one another. To give a brief summary, Kevin Can F**K Himself depicts the plight of a working-class white woman trapped in a multi-camera television sitcom (with laugh track to boot), but whose own affective milieu is that of a realist, dismally lit melodrama. We look in on her character’s private fantasies (about her marriage, upward mobility, and visions of the good life) and see them shatter as she gradually chokes on the aesthetic realities of her gendered class position. What’s unique about the show, in contrast to another genre mutant like WandaVision (Disney+, 2021- ), is the extent to which it holds the dueling forms of schlocky sitcom and #MeToo-era thriller in tension. That’s the narrative thrust of each episode: to ensure that the one doesn’t interrupt the coherence of the other, all while doubling down on the spectacle of their eventual conflagration. What will happen when serialized female suffering and episodic male disavowal lose the thin membrane of affective distance that holds them apart? This is the unresolvable contradiction of the show.

Other genre mutants take bolder risks with aesthetic rupture and its leakage into the collective politics of social difference and materialist conflict. Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You (HBO, 2020), an absurdist dark comedy about the traumas of anti-Black racism and sexual violence, asserts resilient laughter against the show’s habitual misrecognition as a humorless drama due to its extremely serious topic. As Rebecca Wanzo argues, IMDY “is artfully crafted around whiplash-inducing changes in generic modes…demonstrating how form can teach us something about living.” Coel’s laughter echoes across the show’s haunting soundscape, viscerally combatting the canned laughter of the culture industry’s 24/7 carnival of dystopian enjoyment. Laughter gives voice to what’s irreparably broken rather than merrily filling the void.

I think often of Berlant’s 2018 essay on “Genre Flailing,” which they define as “a mode of crisis management that arises after an object, or object world, becomes disturbed in a way that intrudes on one’s confidence about how to move in it.” Genre flailing thus provides an affective escape hatch from utter self-rupture (i.e., the stuff of Victorian female hysteria) without cynically retreating to a norm that’s already proven its abysmal failure. Genre mutants, in my book, can become lightning rods for the collective theater of institutional struggle and unstoppable protest. Their value is specifically not literal or even directly knowable. They orient us toward a reality that’s no less salvageable for its imminent dissolution into thin air.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1: Kipo and the Age of the Wonderbeasts (Netflix, 2020).

- Figures 2 and 3: Stills from the birthday party scene in Parasite. Slapstick and horror genres collide with a cake-in-the-face gag and knife-in-the-heart stab (author’s screen grab).

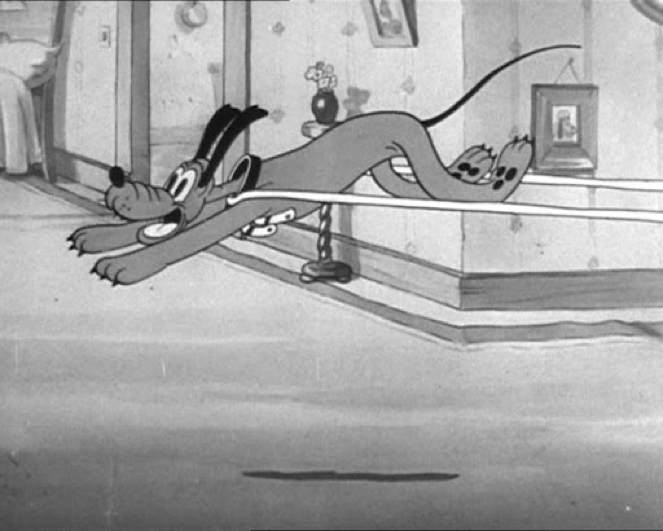

- Figure 4: “Playful Pluto” cartoon featured in the genre-hybrid Hollywood film comedy, Sullivan’s Travels (Preston Sturges, 1941) (author’s screen grab).

- Figure 5: Two stills comparing the dueling genres of Kevin Can F**k Himself.

Adorno, T.W., trans. John MacKay (1996). “Chaplin Times Two.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 9(1), 57-61.

Berlant, Lauren (2011). Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press.

Berlant, Lauren (2008). The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture. Duke University Press.

Berlant, Lauren (2018). “Genre Flailing.” Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry. http://capaciousjournal.com/article/genre-flailing/.

Rebecca Wanzo (2020). “Rethinking Rape and Laughter: Michaela Coel’s ‘I May Destroy You.’” Los Angeles Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/rethinking-rape-and-laughter-michaela-coels-i-may-destroy-you/.

For my fourteenth birthday party sleepover, a friend brought a VHS copy of Natural Born Killers. There is a scene in particular that adopts the stylistic trappings of a late-50s/early 60s sitcom including a laugh track, title card, credits, and so on where Rodney Dangerfield plays the sexually-abusive father of Juliet Lewis’s character. (I’d link a clip here, but I can’t bring myself to watch it again and can’t really give all the necessary content warnings.) It is unquestionably the most upsetting thing I’ve ever seen. And I don’t mean this in any kind of quantifiable, objective sense. I was and am subjectively upset to the point where the memory still puts a knot in my stomach, some 25+ years later.

A few odd other highlights from my list of the most disturbed I’ve been by moving images:

-a slasher parody episode of The Facts of Life

-the “Elephants on Parade” sequence of Dumbo

-a scene in The Cell depicting an attractive, nude woman dancing sexually. The problem is that she is dead and attached to a machine that creates the uncanny movement.

In all of these cases, there seems to be an element of surprise as well as juxtaposition. A slasher barges in on a “family sitcom” (well before “Too Many Cooks”), abstraction and threat emerges from a children’s cartoon, pornography arises out of body horror. A simple, yet meaningful, distinction here is between the genres that arouse “good” feelings like intimacy, laughter, and arousal versus those that arouse “bad” feelings like fear and disgust. The use of sitcoms here as well as in many of your examples seems especially notable for the connotations that the genre has with family, close friendships, feelings of intimacy, and (as you note) a kind of safe (if somewhat boring) stability. Particularly when we think about some of the current discourses regarding young adults’ delaying or forgoing parenthood and home ownership in the face of economic instability and the impacts that these choices have on the world at large (by, for example, increasing the total output of carbon).

My question then, is related to a sense of trying to grapple why these examples struck me (and I hope others) as so notably disturbing. From the perspective of someone often engaged with the comic potential of genre-mixing in parody, this is interesting. I’m wondering how we might consider similar mechanisms of surprise and juxtaposition that somehow hit harder than other, less stark, genre mixing? The presence of zombie-like creatures in a fantasy series like Game of Thrones seems just kinda ho-hum by comparison. I would generally agree that genre markers that point to “the good life” are the major factor here, but it strikes me that there is something also going on with regard to the apparent gaps between the genre collisions that speaks to the affective potential of this technique.

My other, less broad, question regards your characterization of the concept of “crisis ordinariness” as a mixing of genres. I had never consciously thought much about the juxtaposition in this concept in terms of genre, even if I am now realizing that I have used the concept to discuss the collision of genres that purport the “real” collide with fictionalized and more fully fictional texts. Rather, I had always been thinking of it more in terms of a kind of Jamesonian “cultural dominant.” I’m wondering if you could just expand on your reading of this concept through the lens of genre. How does it compare to the other, more obviously generic, collisions you cite as well as how you see that concept playing out in specific examples. “Crisis coverage” in news and “crisis fiction” in various forms seem to be forms we could identify without too much trouble. What does “ordinariness” as a genre look like? The sitcom comes to mind, but there must be additional facets to this way of understanding it, right?

Sometimes unfairly viewed as the lesser version of Facebook, Twitter is the place where everything seems to happen instantly. Birthplace of the now now-ubiquitous internet facet, the hashtag, Twitter is the best place to be if you like to be on top of the latest breaking news as it happens. Follow your favorite content creators, actors, or crazes, and follow all the news, impressions, and opinions as they roll in.