Dramas of grief: television and mourning

Helen Wheatley / University of Warwick

In 1994, bell hooks proposed that Hollywood depicted the ‘sensational heat of relentless dying… with no time to mourn’ (hooks, 1994: 10). Here the US media is characterised as dealing with death at a fast pace, focusing on the material, but not the emotional, consequences of it. Laura E. Tanner makes a similar case when she argues that ‘images of the dead in contemporary American mass culture often direct our attention to death by engaging in representational processes that obscure the embodied dynamics of loss in the very process of depicting the lost body’ (2006: 211). Spectacular death on screen might therefore be seen as leaving us with a body, flayed, dismembered, bleeding and decomposing, but with no sense of how or by whom that body (or the person who once inhabited it) might be mourned.

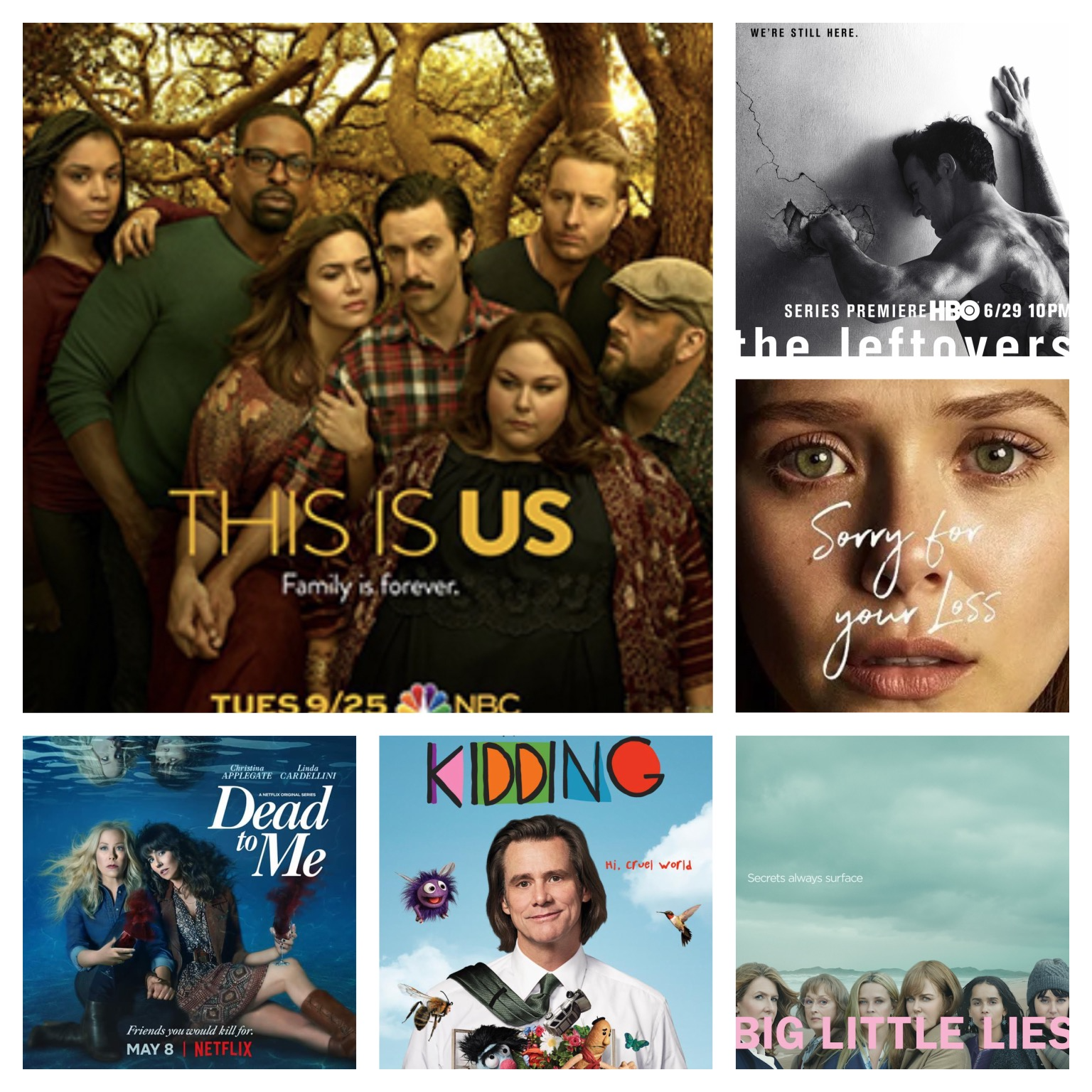

During the course of writing my forthcoming book, Television/Death, I have come to recognise that whilst we are frequently offered a ‘television of attractions’ in contemporary television dramas, in which the corpse is rendered the spectacular object of a simultaneously fascinated and appalled gaze (see Wheatley (2016) for an earlier exploration of this), an alternate strand of programming has developed which precisely focuses on the absence of this body: the television of grief. At some point in 2019, I realised that nearly all of the contemporary US serial dramas I had been watching for pleasure over recent years focused on a central character or characters going through the emotional processes of grief and mourning. From the complex family dramas This is Us (NBC, 2016-) and Big Little Lies (HBO, 2017-2019), to shows such as The Leftovers (HBO, 2014-2017), Kidding (Showtime, 2018-), Sorry for Your Loss (Facebook Watch, 2018-2019) and Dead to Me (Netflix, 2019-) which more explicitly announced themselves as explorations of bereavement and loss, grief seemed to be suddenly everywhere on television. This was precisely not the spectacular deaths of Hannibal (NBC, 2013-2015) or Game of Thrones (HBO, 2011-2019) or The Walking Dead (AMC, 2010-), but dramas that were more interested in exploring what was experienced after a death, rather than the death itself. The deaths at the centre of these series typically took place either before the beginning of the drama or were not revealed until some way into their temporally complex narratives. The bodies of the dead were, therefore, precisely not at the centre of these narratives which explored the aftershocks of death.

Contemporary dramas of grief and bereavement explore the complexity of grief, its multifaceted nature, its long duration and its seriality. In doing so they reflect recent shifts in thinking about the nature of grief away from what psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross mapped out in her 1969 book On Death and Dying as the five stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance) to an experience characterised as having a more messy and complicated structure. As Kenneth J. Doka explains:

We no longer view grief as a series of universal stages — rather we now see a continuum of reactions, very personal pathways that encompass the range of reactions individuals have to loss — from resilience to more complicated forms of grief. We recognise the variety of losses that can engender grief — not just a death… We understand that grief is not about detachment but rather that we retain continuing bonds with people we loved.(2018: 37)

Recent theories of grief therefore recognise the shape of grief as individuated and non-linear, perhaps cyclical and episodic, and, often, continuous, a series of oscillations between feelings and experiences that do not come to a complete end (Thompson, 2017: 138). In these new theories of grief, we learn to live with grief, rather than actively shrug it off or move through and away from it. It makes sense then that a verisimilitudinous representation of grief in serial drama for television presents the experience of it and the emotions attached to it as complex and ongoing. These programmes also often remind us that grief is an individual experience, not a one-size-fits-all pattern.

The multiple strands of long-form serial narrative also allow for an examination of grief from multiple points of view, with multiple characters reacting in a variety of ways to the same death. This turn in contemporary US television therefore shows us that television can be understood as a medium of mourning par excellence. The contemporary multi-part drama series I’ve been writing about are particularly well-able to depict the processes of grief for three specific reasons. Their long duration, serial form, and their playfulness with narrative time (what Mittell would call their ‘narrative complexity’ (2006)) all allow for a verisimilitudinous depiction of the experience of grief. Aaron’s proposal that that ‘dull ache of mourning’ is ‘rarely seen’ on screen (2014: 1) cannot be upheld if we are to look at contemporary US television drama; by contrast, that dull ache is everywhere. There is, arguably, something inherently televisual about these three identifying characteristics of narrative form which transcends the platform for which the drama is made; television’s extended duration, temporal volatility and constant returns are seen in programmes produced for broadcast TV (e.g. This is Us for NBC), streaming services (e.g. Dead to Me for Netflix) and social media platforms (e.g. Sorry for Your Loss for Facebook Watch). In their seriality and their extended length, they are most definitely television and not film. Thus each of these programmes explore grief and mourning in a quintessentially televisual way. Contemporary US serial drama depicts mourning in narratives which expand and oscillate (seemingly) endlessly, allowing for the exploration of the multi-faceted dimensions of grief.

One of the most striking examples of this is seen in the NBC series This is Us , which follows the story of the Pearson family across 90 episodes and five seasons (so far). We are not in fact aware that Jack Pearson (Milo Ventimiglia), the father of the family at the centre of the narrative, has died at the beginning of the series, with an episode structure that skips constantly between the past and the present, (documenting the lives of this family back and forth). However, from the very beginning of the series we see the repercussions of that death for his three children, Kevin (Justin Hartley), Kate (Chrissy Metz) and Randall (Sterling K. Brown), as they respectively suffer with depression and alcoholism, feelings of misery and comfort eating/chronic obesity (which is directly tied to grief in the narrative), and crippling stress and anxiety. Throughout the series, this grief grows ever-more complex (these three are joined by multiple other characters experiencing other forms of grief and loss, and their own story arcs are complicated by multiple experiences of grief). This is Us therefore shows us that there is a longevity and a seriality to grief: bereavements will keep on coming, and continue to be felt over and over again, throughout our lives. The structuring of long-form serial narratives around flashbacks and flash-forwards in programmes such as This is Us depict grief as a constantly comparative state in which we contemplate life before, and life after, a loss. For the Pearson family, the constant flashbacks to the children’s early and teenage years initially establish the stakes of what and who is lost and mourned in the scenes in the present: each of these different time frames feature prominently in each episode. Later, as the series progresses, these flashbacks enable both characters and viewers to question the version of the past, and the remembered figure of Jack, that has formed for each of the characters, and to see how individual responses to grief in the series develop. The past becomes a complex site of contested histories and contradictory family stories and subsequently the series emphasises that our experiences of grief make us who we are. This is Us is thus a striking example of the complex, messy narrative of grief made for contemporary US television.

Image Credits:

- A collection of family dramas that explore loss. (author’s collage)

- The actors who portray This is Us‘s Pearson family across generations.

Aaron, Michele (2014) Death and the Moving Image: Ideology, Iconography and I, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Doka, Kenneth J. (2018) ‘Understanding grief: Theoretical perspectives’ in Candi K. Cann (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Death and the After Life, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 30-39.

hooks, bell (1994) ‘Sorrowful black death is not a hot ticket’, in Kate Gateward and Murray Pomerance (eds) Sugar, Spice and Everything Nice: Cinemas of Girlhood, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. 91-102.

Kübler-Ross, Elizabeth (1969) On Death and Dying, London and New York: Routledge.

Mittell, Jason (2006) ‘Narrative complexity in contemporary American television’, Velvet Light Trap, 58, Fall, 29-40.

Tanner, Laura E. (2006) Lost Bodies: Inhabiting the Borders of Life and Death Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Thompson, Neil (2017) ‘Existentialism’ in Neil Thompson and Gerry R. Cox (eds) Handbook of the Sociology of Death, Grief and Bereavement, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 128-140.

Wheatley, Helen (2016) Spectacular Television: Exploring Televisual Pleasure, London: I.B. Tauris.

—- (2023, forthcoming) Television/Death, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Grief drama clips