Remix a Myth & Sing a Black Girl’s Song

Ravynn K. Stringfield / William & Mary

Remix a Myth & Sing a Black Girl’s Song [1]

Whenever a new piece of remixed media enters contemporary discourse—often a classic story retold and recast with Black people who had originally not been included—Black viewers and readers often have different versions of the same conversation. Is it better to insert Black people into stories that purposefully excluded us or to simply make our own, new stories? I argue that this is often a “both/and” situation. Rather than attempt to determine which is “better” representation, I argue that the creation of novel stories centering nuanced depictions of Black life are critical and that remixed stories, especially myths and legends, offer fertile ground to innovate stories so as to make them our own.

The practice of remixing itself is ingrained in Black cultural practice: sampling is a characteristic of hip hop; taking scraps of food and reimagining them into a feast formed the creation of American soul food; and weaving otherwise discarded bits of worn cloth into intricate quilts remain valuable skills. For Black women and girls, this practice allows for a playful form of experimentation that can result in exploring vehicles for self-making, especially in the digital age. Recently, Greek mythology has proved to be a foundation on which to riff: American Studies scholar Grace McGowan argues Lizzo and Cardi B in their “Rumors” video are but the latest in a long line of Black women to reclaim classical figures to insist upon their own interpretations of joy and beauty.

I would argue that this is equally true of singer Chlöe Bailey’s first solo single music video, “Have Mercy.” One half of the sister duo, Chloe x Halle, Bailey’s “Have Mercy” video has been interpreted by journalists as a 21st century riff on the myth of Medusa, in which she heads a sorority that lures men in only to turn them to stone.

Transfiguration of men also is a trait of Greek witch Circe, who is often best known for turning Odysseus’ crew into pigs in Homer’s The Odyssey. The use of transfiguration in this particular media brings to mind the work of digital humanist Moya Bailey, who writes of digital alchemy, or Black women’s ability to “turn the everyday digital media into valuable social justice magic.”

In her 2021 book Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance, Dr. Bailey encourages readers to think about the ways Black women transform media into reclamatory narratives. “Have Mercy” uses these mythic stories and themes to build Chlöe’s own persona as a young performer, drawing energy from the ability to reimagine these stories as her own. The sorority imagery reminds the viewer that though this is an independent project, one of Bailey’s main concerns is sisterhood and paying homage to older generations. Part of her influence comes from the artistry of Beyonce—Chloe’s Clueless (1995) aesthetic also draws energy from the work of the HBCU marching band inspired Homecoming (2019) film.

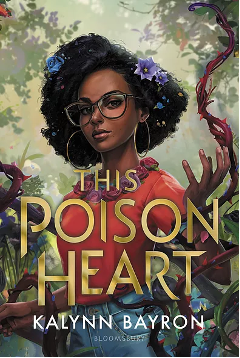

Using myths and classics as the foundation for new opportunities for Black girls to self-make is also popular in the young adult (YA) literature sphere. YA fantasy author Kalynn Bayron’s This Poison Heart (2021) also makes use of Greek mythology to craft a queer coming-of-age fantasy story centering Briseis Greene who inherits an estate from late biological aunt that houses a secret—and deadly—garden. Bayron’s text is not simply a retelling; it speculates about how every piece of the world could be different if Black girls wrote magic into their stories. In Briseis’ world, the people who surround her are Black and queer, she lives in a community characterized by it’s commitment to defunding the police, and has space to stretch herself into who she is meant to be, in her magic and in her life. [2]

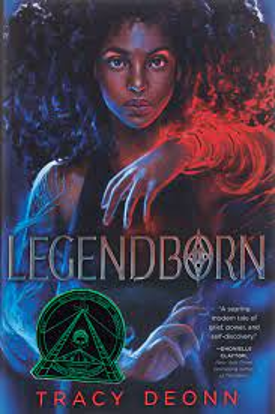

Tracy Deonn opts to use Arthuriana as a base for her magical Black girl epic, Legendborn (2020), set in contemporary North Carolina—specifically on University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s campus. In an interview with Black fantasy bookstagrammer Bezi Yohannes and I for our collaborative podcast, Dreaming in the Dark, Deonn explains that giving her protagonist, Bree, a connection to the Welsh myth system came secondary to finding a vehicle to work through a story about a young Black girl’s grief and rage. Bree is learning who she is against the backdrop of several deep, complicated and inextricable histories, often characterized by violence and loss, in a place with its own fraught history. Deonn asks us to consider what it means for Black girls to be able to craft their own identities in spite of histories so big they threaten to define us themselves. It is a novel length response to the foundational quote by Audre Lorde: “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”

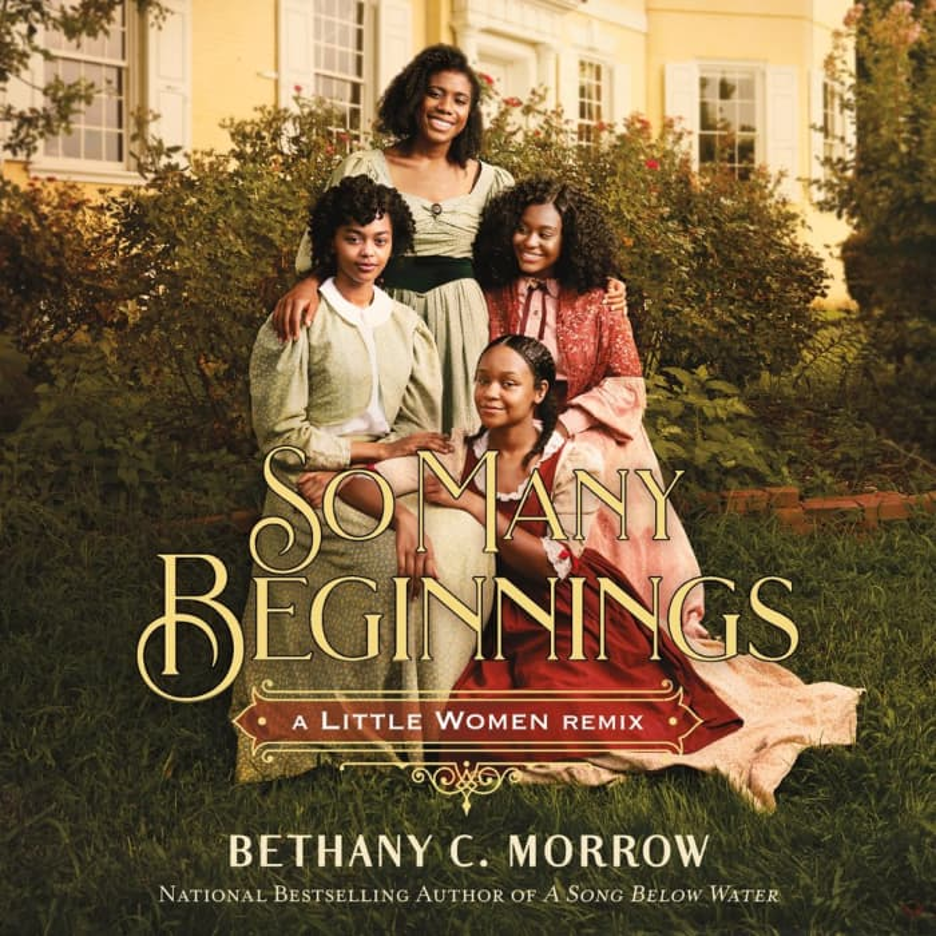

This stance of considering what it means to pursue self-determination in the face of the truth of the past, plagues Bethany C. Morrow’s most recent work: So Many Beginnings: A Little Women Remix (2021). Rather than imagining a classical myth, Morrow takes a swing at what might be considered part of an American mythology: Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1869). Morrow shifts the context, which is what I consider to be the most crucial part of reimagnings and remixes: it does not simply color in white characters and story with a brown crayon. Instead, it asks how the themes of an iconic story would make sense for Black American cultural context. As such, Morrow’s So Many Beginnings takes place on Roanoke Island, exploring what it might have been like for freed Black people in the midst of the Civil War. She takes this opportunity to shift this narrative of sisterhood, motherhood and patriotism, to consider questions also at the forefront of Black minds in the 19th century: the conditions of freedom and understanding the seemingly precarious and fragile nature of it, the trauma of forced separations and the lasting impact of physical labor, but also the consistent ability to craft deep kinship ties with those even outside of the bloodline. Black women historians in particular have considered this type of work reclamatory work. Jessica Marie Johnson writes of the null value and Saidiya Hartman of critical fabulation, choosing to, wherever possible, acknowledge the presence of those possibly unnamed but present in the archive and reasserting their humanity.

Remixing and reimagining is critical work, and in the case of the historical work I cite above, can be heartbreaking labor, but remains a source of infinite possibility and site of play. It allows for Black girls to do what they do best: innovate and create. [3],[4] Digital media and the magic Black girls bring to it makes space for us to reimagine and reinvent ourselves as much as we want. [5] We are simply geniuses at making something marvelous out of nothing. It makes one consider what else might be possible if we follow the contours of our imaginations.

Image Credits:

- Picture of Chlöe alongside a statue in her music video “Have Mercy.”

- The Poison Heart by Kaylynn Bayron.

- Legendborn by Tracy Deonn.

- So Many Beginnings by Bethanny C. Morrow.

- Title inspired by Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When The Rainbow is Enuf: “Somebody/anybody sing a black girl’s song…let her be born & handled warmly.” [↩]

- Kalynn Bayron spoke about This Poison Heart to co-host Bezi Yohannes and I for our Black fantasy podcast, Dreaming in the Dark. Forthcoming, Fall 2021. [↩]

- Gaunt, Kyra Danielle. The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop. New York University Press, 2006. [↩]

- Brown, Ruth Nicole. Hear Our Truths: The Creative Potential of Black Girlhood. University of Illinois Press, 2013. [↩]

- Johnson, Jessica Marie, and Kismet Nuñez. “Alter Egos and Infinite Literacies, Part III: How to Build a Real Gyrl in 3 Easy Steps.” The Black Scholar, vol. 45, no. 4, Oct. 2015, pp. 47–61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2015.1080921. [↩]