Creative and Participatory Responses to Disinformation: The Case of the Bees 🐝 in the 2018 Colombian Presidential Elections

Andres Lombana-Bermudez / Universidad Javeriana

Jajajajaja pic.twitter.com/n5Q1kRH98f

— Alvaro Andrés – #TiemposDeCuarenta (@KtuluRed) June 9, 2018

On the morning of Saturday, June 9, 2018 at La Loma, Cesar, a small town located in the Caribbean region of Northern Colombia, a swarm of bees attacked the attendees of a presidential election rally organized by the rightwing party Centro Democrático (Democratic Center). The leader of the party and ex-president Alvaro Uribe Velez cancelled his speech on behalf of his protégé, the presidential candidate Iván Duque, and the political meeting was suspended. This incident happened a week before the runoff presidential election that confronted Duque against Gustavo Petro, the candidate of the left party Colombia Humana and a former rebel of the M-19 guerrilla. In the middle of a polluted information environment, a presidential race characterized by personal attacks, and a society divided between the supporters and opponents of the peace accord signed in 2017, the episode of the bees rapidly became the material for producing misleading content with the intention to harm the Colombia Humana candidate.

Before noon, Uribe published a message on Twitter from La Loma Hospital asking for medicines that could help the people stung by Africanized killer bees. The tweet quickly circulated among across the networks of his more than four million followers, catching the attention of journalists, influencers and politicians. Two hours later, Fernando Araújo, a senator from Centro Democrático published a tweet from Cartagena de Indias, one of the main cities in the Colombian Caribbean, stating that at La Loma pacificists “threw” bees against citizens as an act of “bio-terrorism.” Minutes later, Natalia Bedoya, a conservative influencer, produced a tweet saying that Colombia Humana’s pacificists and Petro’s followers promoted hate with terrorist acts. Although the police investigations quickly confirmed that it was the landing of a helicopter that disrupted a hive and altered the bees, several far-right politicians and influencers continued to amplify and publish misleading content on social media, obscuring the evidence, and building up the false narrative about a terrorist attack perpetrated by members of left party.

En la Loma, Cesar, lanzan abejas contra los ciudadanos en reunión con el presidente Uribe.

— Fernando Nicolás Araújo (@FNAraujoR) June 9, 2018

Bio terrorismo. Pacifistas de boca pero con odio.

Hay personas afectadas.

En la Loma, Cesar, los pacifistas de la ‘Colombia Humana’ lanzan abejas contra los ciudadanos en reunión con el Presidente Uribe.

— Natalia Bedoya (@natiibedoya) June 9, 2018

Y mientras el candidato firma en mármol, sus seguidores con actos terroristas promoviendo su odio

Despite the absurdity of the narrative, it resonated among far-right and the Centro Democrático sympathizers. As a piece of disinformation with political motivations, the falsehood agitated the feelings of hate, anger, and fear towards the peace activists, the left, and Colombia Humana’s presidential candidate. However, in contrast to previous disinformation pieces produced by the far-right in Colombia, the hoax about the terrorist bees attack was quickly debunked by a collective civic action that was able to not only expose its lies and stop its propagation, but also to transform a fear-inducing narrative into one of solidarity. Such creative and quick collective response revealed the potential of mobilizing digital participatory culture for reducing the spread of disinformation in a polluted information environment.

Information disorder in the Colombian context

Contemporary networked and hybrid media ecosystems are polluted. According to Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan (2017), we live in an age of information disorder characterized by the circulation, production, and consumption of disinformation, misinformation, and malinformation. Disinformation can be understood as “content that is intentionally false and designed to cause harm. It is motivated by three distinct factors: to make money; to have political influence, either foreign or domestic; or to cause trouble for the sake of it” (Wardle and Dekhsan). Although disinformation is not new and has existed for a long time in modern societies, its deployment using the digital tools and networks has changed its scale, cost, speed, agents and dynamics.

During the last years, elections in several democratic countries around the world have been disrupted by the strategic use of online disinformation campaigns. For instance, online disinformation operations attempted to influence the voters in the presidential elections of the U.S. (2016), France (2017), Brasil (2018), and India (2019). In Colombia, a country with a long history of armed conflict and political violence, online disinformation campaigns have been used in recent elections and with the goal of deepening the division between the supporters and opponents of the peace negotiations between the government and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Unfortunately, the context of peacebuilding and post-conflict transition in Colombia, with all its possibilities of social, cultural and political transformation, has triggered an increasing pollution of the information environment and created a climate appropriate for disinformation storms.

The outcomes of the 2016 peace plebiscite proved the effectiveness of disinformation operations in Colombia when the “No” vote, promoted by the Centro Democrático and the far-right political elite, won by a small margin over the “Yes.” The political campaign for the “No” deployed disinformation both online and offline in order to exploit the political beliefs and divisions generated during a 50 years old war between the FARC guerrillas and the Colombian state. The “No” campaign successfully mobilized the feelings of fear, anger, and indignation of many citizens towards the FARC combatants, the left, transitional justice, and the possibility of a post-conflict society (Gonzales 2017; Matanock and García-Sanchez 2017).

The repertoire of disinformation pieces created during the plebiscite campaign by the far-right included misleading narratives and fabricated content like the conspiracy theory of a “Castro-Chavism” communist plan to overtake the Colombian state and give away the country to the FARC. Such disinformation spread quickly and broadly, and was difficult to debunk. By using it, the Centro Democrático and the far-right were able to radicalize conservative citizens, and to deepen the political polarization around the peacebuilding process. Due to the success of these disinformation pieces during the plebiscite campaign, they were re-used during the presidential elections of 2018 with the purpose of discrediting and attacking the left and centrist political parties.

Transforming fear into solidarity: Meaning-making and imagination at work.

Meaning-making is essential to the production of media artifacts and for the thriving of digital participatory culture. Citizens with access to digital tools and networks, and with media literacy skills regularly practice meaning-making when they create and circulate visual memes, video remixes, hashtags, and other artifacts. When doing this kind of work people re-signify and re-contextualize symbolic resources, create links among different cultural media texts, and participate in digital cultures (Wiggins 2019). Meaning-making practices are powerful. They enable citizens to imagine and build discursive spaces, communities, and identities. From the hashtags produced to coordinate social movements, to the visual memes created to reaffirm political identities, citizens around the world have leveraged the power of meaning-making with different motivations and purposes.

In the case of bees that I introduced before, Colombian citizens mobilized digital participatory culture with the objective of diminishing the spread of disinformation. Using creativity, imagination, and digital practices, hundreds of citizens responded to the misleading story of a bio-terrorist attack by producing and circulating a variety of media artifacts (visual memes, videos, hashtags, emojis, and texts) on social media platforms. While some of these artifacts critically questioned and confronted the falsehoods with evidence, others mocked the far-right creators ridiculing the absurdity of the hoax. Still other media artifacts elaborated a powerful counter-narrative that, remixing symbols from the hoax with resources borrowed from popular culture, was able to bend the portrayal of terror into a story of solidarity. For example, one visual meme juxtaposed a photograph of Petro’s face over the head of The Simpsons’ (Fox, 1989–) Bumblebee man; another meme photoshopped an image of the Maya the Bee cartoon character adding the logos of Colombia Humana to her wings; and hundreds of Twitter and Facebook user profiles were modified to include the bee emoji, 🐝 .

Me llamo la abeja 🐝 maya y quiero qué Petro sea ml Presidente. #AbejasCastroChavistas pic.twitter.com/7SpSq6Uibr

— Fiallo-Arake Nancy 🌻📚🦖🦕🐳🐘🦒🦏🌻🚇✈️🌎👠 (@ArakFialloNancy) June 10, 2018

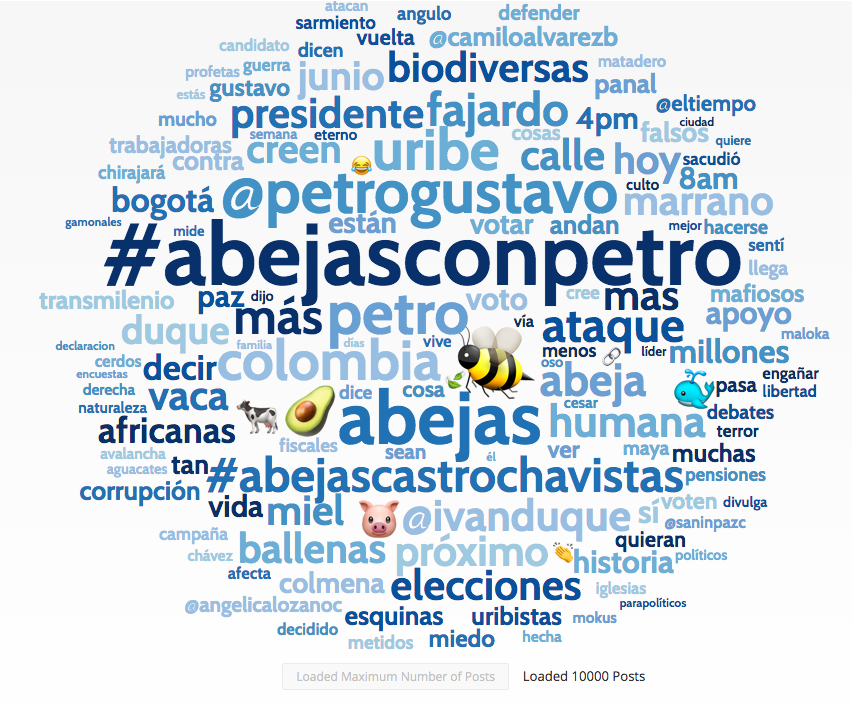

One of the most important media artifacts used during the civic response to disinformation was the Twitter hashtag. The creation and circulation of two hashtags that rapidly became trending topics on the Colombian Twittersphere was crucial for catching the attention of diverse publics (including the mainstream media) and motivating citizens (particularly sympathizers of Colombia Humana) to participate. The hashtags became trending topics the same day that the disinformation started to propagate (June 9, 2018) and continued to be popular tendencies until the election day (June 17, 2018). As some researchers have pointed out, Twitter hashtags are strategic tools for technopolitics, particularly for social protests and algorithmic resistance (Jackson et al., 2020; Treré, 2018). Both #AbejasConPetro (BeesWithPetro) and #AbejasCastrochavistas (BeesCastrochavists) took the “bees” symbol from the misleading narrative of a terrorist attack, and playfully re-signified it. On the one hand, the hashtag #AbejasConPetro gave the “bees” a new meaning as supporters of Gustavo Petro, the presidential candidate of Colombia Humana. On the other hand, by placing the “bees” next to “Castrochavismo,” a symbol created by the Colombian far-right and used in several conspiracy theories, the hashtag #AbejasCastrochavistas exaggerated and ridiculed the hoax. Both hashtags were used for demonstrating solidarity and affect towards the left, and expressed the creativity and humor of the citizens that participated in the collective response to disinformation. Moreover, the hashtags functioned as a networked forum that citizens could use for coordinating the circulation and production of a rich variety of media artifacts.

The case of the bees 🐝 during the 2018 Colombian presidential elections shows that mobilizing digital participatory culture is an effective approach to diminish disinformation. By rapidly responding to a misleading narrative with the creation and circulation of multiple media artifacts, and by actively engaging in meaning-making, Colombian citizens were able to not only debunk a disinformation piece, but also to stop its propagation.

Image Credits:

- Tweet by @KtuluRed with photoshopped image of The Simpsons’ Bumblebee man photoshopped with the face of Colombia Humana presidential candidate, from June 9, 2018.

- Tweet by a politician and senator, @FNAraujoR, from Centro Democrático condemning a bioterrorist attack, from June 9, 2018.

- Tweet by a conservative influencer, @natiibedoya, accusing pacifists and Petro’s followers of promoting hate with terrorist acts, from June 9, 2018.

- Public mural in Caracas, Venezuela, displaying Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez. “Castro-Chavismo” is a made-up term to refer to Latin America communism. (Source)

- Visual meme of Maya de Bee photoshopped with the logos of Colombia Humana party and a caption that says in Spanish: “My name is Maya de Bee and wants Gustavo Petro to be my president.” Tweet by @ArakFialloNancy from June 9, 2018.

- Wordcloud visualization displaying the frequency of the #AbejasConPetro and #AbejasCastrochavistas in a sample of 1000 Tweets published between June 9 and June 17, 2018. (Author’s own image)

González, M.F. (2017) La «posverdad» en el plebiscito por la paz en Colombia. Revista Nueva Sociedad 269, Mayo – Junio 2017. Recuperado de

Jackson, S.J, Bailey, M. and Foucault Welles, B. (2020) #HASHTAGACTIVISM: Networks of Race and Gender Justice. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Matanock and García-Sanchez (2017) The Colombian Paradox: Peace Processes, Elite Divisions & Popular Plebiscites. Daedalus 146 (4), 152-166.

Treré, E. (2018). From digital activism to algorithmic resistance. In: Meikle, G. ed. The Routledge Companion to Media and Activism, Routledge Media and Cultural Studies Companions, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 367-375.

Wardle, C. & Derakhshan, H. (2017) Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe report, DGI (2017) 9.

Wiggins, B. E. (2019). The discursive power of memes in digital culture: Ideology, semiotics, and intertextuality.