Reactionary Influencers and the Construction of White Conservative Victimhood

Erika M. Heredia and Mel Stanfill / University of Central Florida

On September 10, 2020, internet provocateur Kaitlin Bennett, who first gained notoriety in 2018 for bringing an assault rifle to the site of the 1970 National Guard massacre of student protesters at Kent State University (see Figure 2), visited the University of Central Florida (UCF).

According to Bennett’s Twitter account, the purpose of her visit to UCF was to ask students about the upcoming presidential elections (see Figure 3). Armed with a microphone, a video camera, and her bodyguard, Bennett stormed the UCF Main Campus, knowing—indeed, intending—that her mere presence would cause chaos. This goal was achieved, and dozens of students confronted and protested her. This was merely one of a string of such stunts by Bennett, who is one of a new category of public personality that we’re calling reactionary influencers, who combine right-wing politics, reality-TV style provocations, and new social media opportunities for fame and fortune.

On one level, Bennett’s persona is a new iteration of an old formulation. In the tradition of figures like Phyllis Schlafly, she is a conventionally attractive blonde white woman who publicly advocates for conservative positions and gains notoriety because conservatism is typically thought of as being antithetical to the interests of women.[1] The political position Bennett takes is pro-gun, nationalist, anti-regulation, anti-communist, and in favor of the privatization of all services provided by the state, including public education such as public universities. Her platform is also enmeshed in the culture wars, hailing a supposed silent majority whose rights have allegedly been taken away by now-privileged minorities. Bennett’s opponents, by contrast, are classified as “leftist,” “Marxists,” and even “domestic terrorists.”[2]

Bennett is also operating within a tradition in terms of how she produces her spectacles, building from reality TV and other prank show formats that cultivate uncomfortable situations to get a desired response on video. As scholars Hobbs and Grafe note in their study of YouTube prank videos, the format has a history that goes back at least to Candid Camera in the 1950s. In the videos she posts, Bennett is confrontational but engaging, armed with statistics and sources researched in advance as she puts those with opposing views on the spot to dispute her. Her Twitter account includes a video in which she mocks one of these put-on-the-spot respondents at the UCF Campus who cannot explain why she considers Donald Trump to be a racist. In such ways, these videos are an example of the ways “pranks are a form of interpersonal humiliation involving a three-way relationship between the one who humiliates, the victim, and the witnesses” (Hobbs and Grafe), as Bennett produces this spectacle of a humiliated progressive for her conservative audience.

Moreover, like other reality TV and documentary before it, Bennett’s footage stakes a claim as “a record of an event that has been minimally influenced by either the process of filming or the process of editing”[3], despite being selected from a broader body of video in the interest of constructing a narrative. That is, viewers don’t get to see the times that Bennett encounters people who can make a cogent argument. In this way, Bennett and her team are able to carefully construct her image, positioning her as an extroverted and sensual white woman capable of silencing her discursive opponents with the power of her rhetoric, an aspirational model for those who share her politics. This is how it looks as she emerges gracefully from an argument with a feminist who identifies her as a white supremacist or arguing with students who cannot back up their statements. This does important cultural work, as “by making the target the victim of disparaging humor, other group members can gain a feeling of group solidarity and cultural superiority” (Hobbs and Grafe), such that the videos work to consolidate in-group feeling among adherents of far-right politics.

What is new about Bennett is her participation in a group of social media personalities we’re calling reactionary influencers.[4] These micro-celebrities[5] combine reactionary politics and the social media influencer economy and include well-known figures such as Milo Yiannopolous and Richard Spencer. Some, like James O’Keefe and Steven Crowder, share Bennett’s “confrontations on video” format. Others, like Blonde in the Belly of the Beast, Lana Lokteff, and Faith Goldy, are also conventionally attractive white women. What they all have in common is that they use social media to reach new populations, largely youth, with the same old slogans repackaged as “edgy” content. As YouTube scholar Becca Lewis describes such influencers, “Blending the ‘glamour’ of celebrity with the intimacy of influencer culture, they broadcast gender traditionalism and performed ‘whiteness.’ In this way, influencers display the way they live their politics as an aspirational brand” (28).

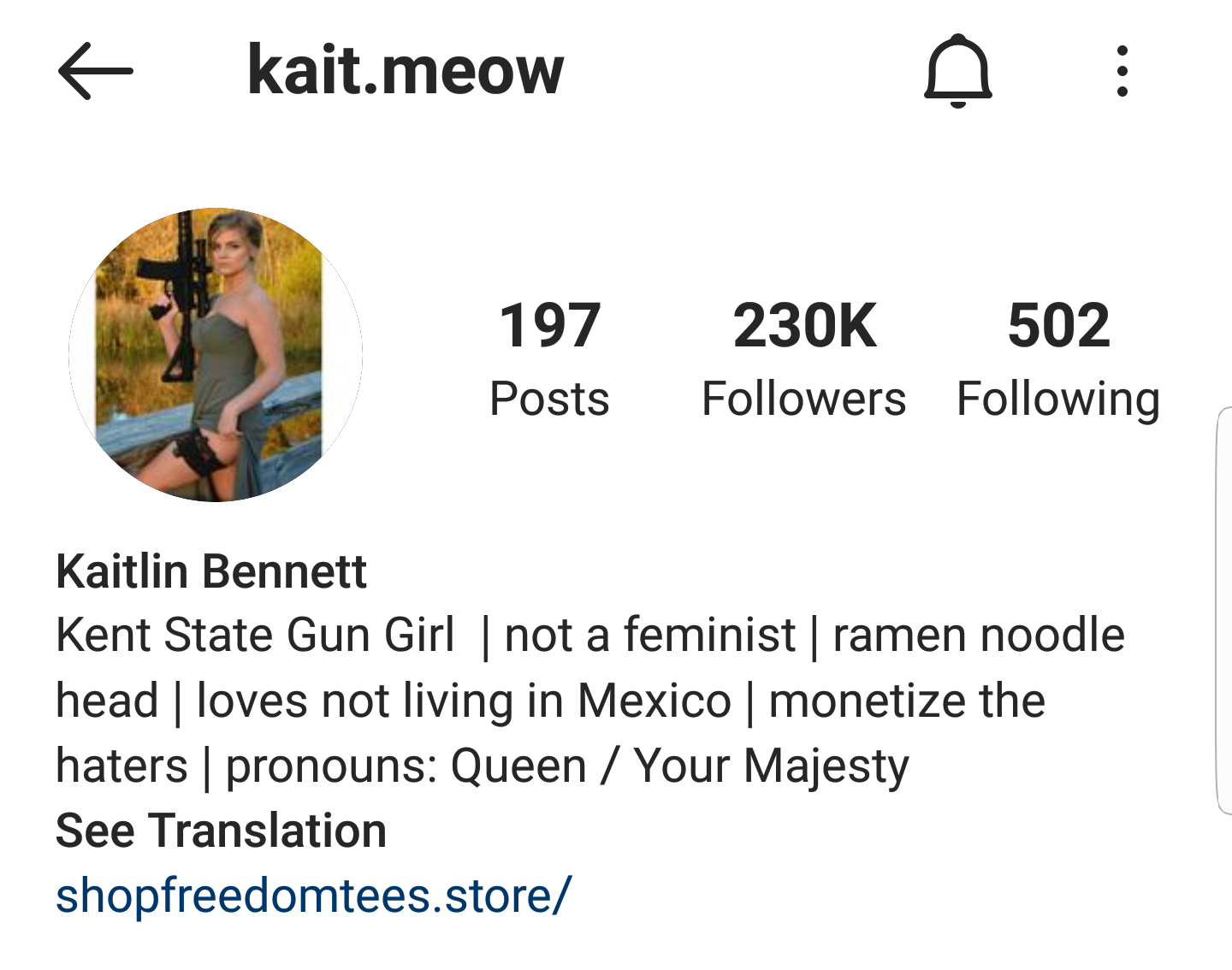

Reactionary influencers, like other influencers, use their social media presence as a source of income, monetizing their brands with ads, sponsorships, and subscriptions. The end result of combining social media monetization with Bennett’s politics and confrontational style is that calculated offensiveness, and even hate speech, become an economic engine, represented in view counts on YouTube, retweets, and mentions that become data and capital. Indeed, in the early 2020 used as our header image above, Bennett claimed that her “haters” served as free advertising, saying “My haters memed me into a lucrative career that lets me travel the country, do what I want, and have a platform to be heard. Thanks so much to everyone that gave me free advertising in 2019.” Similarly, her Instagram profile declares “monetize the haters” (see Figure 4).

However, a seemingly curious thing happened in the midst of memeing her way into a lucrative career and intentionally sparking conflict: Bennett positioned herself as a victim “assaulted” by a “violent mob” that required her to leave UCF’s campus. We argue that this is the actual purpose of the reactionary influencer’s confrontational format—not saying the offensive out of a deep love of free speech, but out of a desire to provoke a negative response from allegedly overly-sensitive “snowflakes” that lets the reactionary influencer stage victimhood and call for the state to take action against opposing speech.

Bennett’s presence at UCF was repelled, formally, for not wearing a mask as required by COVID-19 policy, and informally, by those who rejected her choice to then wear a Make America Great Again mask, associated with the white nationalist rhetoric of Donald Trump, on a campus where the defense of diversity is a fundamental aim, and particularly doing so during Hispanic Heritage Month. After running through a campus eatery purportedly chased by a “left-wing mob,” Bennett posted a video on Twitter with the caption: “My message to @realDonaldTrump is simple. It’s time to DEFUND public universities. Not another penny in taxes should go to these left-wing indoctrination centers! #DefundUCF.” By this logic, her influencer tactics to package and market right-wing views are legitimate speech, but those who disagree with her must have been “indoctrinated.” Her appeal to the president to take punitive action against her ideological opponents gained traction in the form of more than 2.5k retweets.

The tweet shows the true meaning of Bennett’s provocation tour of college campuses. She seeks not to exercise her own right to speech, but to incite counterspeech in order to enable its repression. The “defund” framing is also no accident. As noted by Bakhtin[6] and later by Foucault[7], a text is inserted in a web of meaning and does not appear by chance, but when the right conditions exist for its emergence; moreover, a text is always dialoguing with and questioning other texts. #DefundUCF emerges in the context of summer 2020’s upsurge of calls to #DefundThePolice, constructing a university where people disagree with Bennett’s views as an institution that abuses the public with taxpayer funds by analogy to the police as an institution that abuses the public with taxpayer funds. While the use of tax funds for public goods such as education has been widely critiqued on the right for years[8], Bennett makes her case explicitly through the tactics of the reactionary influencer, combining the amplification of social media with a cultivated confrontation and the mainstream tendency to see white women as easily victimized. In this way, she seeks to bring the power of the state to bear against speech she disagrees with, while alleging that her own speech is the one being harmed.

Image Credits:

- @KaitMarieox‘s Tweet from Jan. 1, 2020.

- @KaitMarieox‘s Tweet from May 13, 2018.

- @KaitMarieox‘s Tweet from Sep. 10, 2020.

- @kait.meow‘s Instagram profile.

- As recent work by sociologist Jessie Daniels has argued, such assumptions ignore the role of such women’s whiteness, which is served by conservative politics and tends to be a more determining factor in their support than their gender. See for example, Daniels, Jessie. 2017. “Rebekah Mercer Is Leading an Army of Alt-Right Women.” Dame Magazine. September 26, 2017. https://www.damemagazine.com/2017/09/26/rebekah-mercer-leading-army-alt-right-women/. [↩]

- This, of course, is particularly ironic given that the Department of Homeland Security identified a right-wing group, white supremacists, as the greatest domestic terror threat in 2020. See https://www.politico.com/news/2020/09/04/white-supremacists-terror-threat-dhs-409236. [↩]

- Sobchack, Thomas, and Vivian C. Sobchack. 1987. An Introduction to Film. 2nd Edition. Glenview, Ill.: Pearson, 347. [↩]

- This category draws from Becca Lewis’s work on what she calls “political influencers” in the “Alternative Influence Network,” but is more specified, in that we name the politics specific to our category. [↩]

- Senft, Theresa M. 2008. Camgirls: Celebrity and Community in the Age of Social Networks. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. [↩]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 2003. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Theory and History of Literature. Vol 8. Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press. [↩]

- Foucault, Michel. 1994. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Reissue edition. New York NY: Vintage. [↩]

- Daniels, Jessie. 1997. White Lies. Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality in White Supremacist Discourse. New York & London: Routledge. [↩]

Love this page…and it has more than one or two pictures on it!!