Televising Deportation: Hierarchies of Suffering in Immigration Nation

Crystal Camargo / Northwestern University

Since its premiere in August on Netflix, the six-part docuseries, Immigration Nation (Netflix, 2020), has received praise for its in-depth look at the U.S. immigration system, examining both Immigration and Customs (ICE) operations and the experiences of undocumented immigrants. Time has called Immigration Nation “the most important TV show you’ll see in 2020,”[1] while The Guardian claims the docuseries “shows the true horror of ICE agents.”[2] The first episode of Immigration Nation features a clip from The Situation Room with Wolf Blitzer (CNN, 2005—), where Blitzer questions Tom Homan‚ then acting director of ICE, about the new zero-tolerance immigration policy.[3] Blitzer asks Homan, “Is this new zero-tolerance policy that the president has supported, that the attorney general announced, is it humane?” As Homan struggles to answer the question, murmuring, “I think—I think. It’s the law,” I realized that I was having a visceral and painful reaction to undocumented immigrants’ representation in the docuseries. While Immigration Nation asks viewers to consider if the new immigration policy is humane, I ask here: what role do undocumented immigrants’ perspectives play in the docuseries? Is their representation in Immigration Nation humane?

Defining what constitutes humane can be problematic and challenging. However, upon the first twenty minutes of Immigration Nation, I was struck by how the docuseries does not grant the same screen time to undocumented immigrants as it does to ICE agents. This uneven representation is just one of many symptoms of a larger problem with how the docuseries constructs and depicts undocumented immigrants’ perspectives and suffering. In this piece, I explore how Immigration Nation politically mobilizes undocumented immigrant people to investigate the state of the U.S. immigration system. The docuseries examines immigration policies from an institutional point of view and only introduces undocumented immigrants’ perspectives as an attempt to elicit a sentimental reaction from the audience. As the daughter of two immigrants, one of whom has experienced the effects and trauma of deportation in the past, the undocumented immigrant representation in the docuseries is heartbreaking. Yet, as a race and media scholar, I am troubled by the mobilization of undocumented immigrant suffering for sentimental political storytelling.

The representation of undocumented immigrants in Immigration Nation operates similarly to Rebecca Wanzo’s description of Black female suffering and sentimental politics in media. In her book, The Suffering Will Not Be Televised: African American Women and Sentimental Political Storytelling (2009), Wanzo traces how, when, and for what reasons Black women’s vulnerability and suffering are represented in media.[4] Using a framework that interweaves race, gender, and stories of suffering, Wanzo argues that the mobilization of affect occurs through sentimental political storytelling, which produces easily legible suffering for white women who are granted compassion and public sympathy. On the other hand, Black female suffering is only made visible when placed within political and social mobilization efforts to help produce institutional and social change. Overall, Wanzo demonstrates how race, gender, and other forms of differences are preserved and reproduced in hierarchies of suffering. We see these same sentimental storytelling dynamics play out in Immigration Nation between ICE agents and undocumented immigrants. The docuseries utilizes sentimental storytelling for both parties, producing unequal hierarchies of suffering.

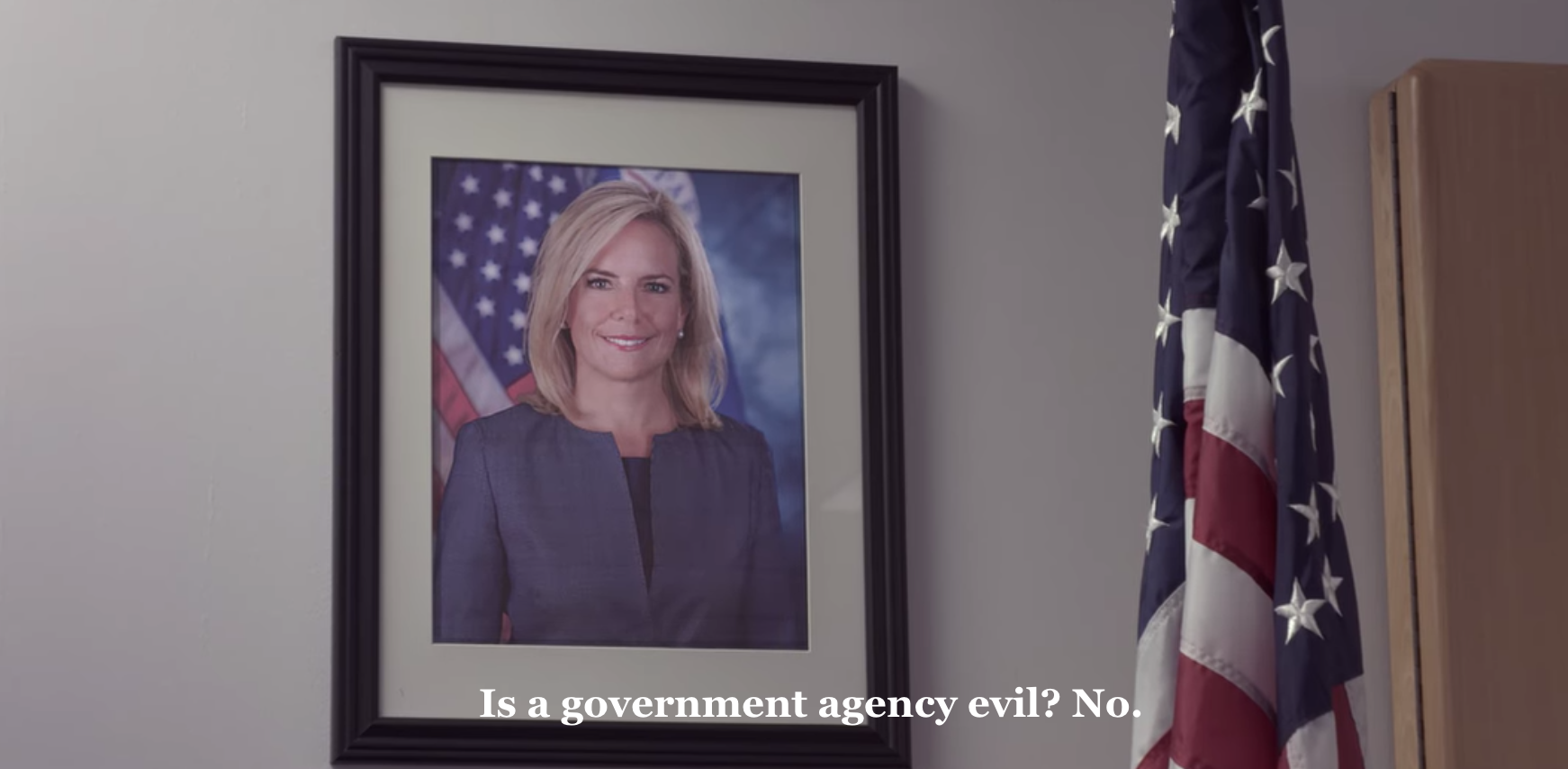

In Immigration Nation, ICE agents are personalized and afforded moral complexity in ways that undocumented immigrants are not. ICE agents in the docuseries are not coded as “good” or “bad.” This is evident in a comment from Becca Heller, a lawyer specializing in human rights. She shares, “What is ICE? It’s a government agency. Is a government agency evil? No. Is every single person inside ICE evil? No. Is ICE a body net doing evil things under the Trump Administration? Yes. Is that the fault of nefarious individuals throughout ICE? No.” This quote perfectly describes how Immigration Nation portrays ICE agents, as they are not deemed villains in the docuseries. Instead, they are understood to be victims of a system, one where the Trump and Obama administrations are blamed for all of the government organization’s wrongdoings. ICE agents are granted time to express their sympathy, moral qualms, and overall feelings of their profession. The content of ICE interviews illustrates diverse views: for example, some reflect on the difficulty of being referred to as Nazis or racists because of their chosen profession; similarly, detaining undocumented immigrants feels “like Christmas” for one agent while another acknowledges that undocumented immigrants “get caught up in politics” and feels some remorse for them. In a review on the docuseries, Ángeles Donoso Macaya states that Immigration Nation “compels the viewer to empathize with those caught up in the immigration system—not people terrorized by raids and deportations, but rather the agents charged with carrying out immigration law.”[5] The docuseries privileges and depicts ICE officers’ complex opinions and asks viewers to identify with the perpetrators of mass incarceration and the deportation machine rather than the detained undocumented immigrants.

Undocumented Immigrants are not afforded the same moral complexity as ICE agents. Instead, the docuseries represent them within culturally accepted narratives of “good” hard-working Mexican and Central American immigrants. They are parents, veterans, and victims of domestic violence. Other than residing in the U.S. illegally, undocumented immigrants in the docuseries have not committed any other crimes, and their stories of suffering are displayed to garner sympathy. Like Wanzo’s analysis of Black women suffering, undocumented immigrants’ suffering is, too, only mobilized for political purposes by showcasing their suffering within preexisting cultural topes and tragic narratives of immigration. In other words, the only screen time and narratives undocumented immigrants are afforded in Immigration Nation is in service of demonstrating the inhumanity of ICE practices and policies as well as to evoke sadness and compassion for their suffering.

For example, the docuseries showcases five diverse confessional-like interviews with ICE agents before introducing one undocumented immigrant story. When the docuseries features their first undocumented immigrant perspective, that interview is strategically placed within two varying ICE agents’ perspectives on collateral arrests. Immigration Nation presents us two different views on that ICE practice, such as one ICE officer who feels zero remorse in enforcing collateral arrest while another appears morally conflicted. The detained undocumented immigrant tearfully expresses how unjust it is that ICE officers arrested him while looking for another undocumented immigrant. He further shares that he is not a criminal but rather an innocent victim. This rhetoric echoes the same sentimental politics expressed by the following ICE agent interview, immediately after, who agrees that undocumented immigrants’ arrest without warrants is unfair. We see the same undocumented immigrant a couple of minutes later on an intimate phone call where he shares fear for his life if deported to his home country. Immediately after this tearful second appearance, we abruptly cut to images of protesters arguing in favor of sanctuary cities, and we never see this man in the docuseries ever again. The undocumented immigrant’s suffering and trauma are politically mobilized to help illustrate individual ICE agents’ moral qualms and promote sanctuary cities. Here, as in the rest of the docuseries, undocumented immigrants’ perspectives are depersonalized as their suffering, pain, and trauma are meant to stand in for all undocumented immigrants.

Some of the promotional marketing for Immigration Nation included how ICE tried to stop the airing of the docuseries and how co-producers Shaul Schwarz and Christina Clusiau fought back against this censorship.[6] This narrative, coupled with positive reviews from some outlets, deems Immigration Nation a progressive text about immigration issues hoping for political and social change. However, as Rebecca Wanzo reminds us, a media object such as Immigration Nation does not have the power to disrupt the state of the U.S. immigration system fundamentally. Furthermore, while Schwarz and Clusiau separate themselves from ICE and the Trump administration’s immigration policies, their docuseries narratively mimics similar structural inequalities between ICE agents and undocumented immigrants in real-life. The series creates a suffering hierarchy illustrating how some bodies and stories are more important to explore than others. ICE agents are given more screen time and complex narratives whereas undocumented immigrants are homogenized, afforded less screen time, and only visible within preexisting cultural and narrative tropes of immigration. Both ICE agents and undocumented immigrants are interpreted as victims in a larger systemic political problem; however, it is saddening, dangerous, and morally wrong that ICE agents in the docuseries are afforded more compassion, sympathy, and understanding than the undocumented immigrants terrorized by them.

Image Credits:

- Netflix’s docuseries, Immigration Nation (2020). (author’s screen grab)

- Kirstjen Nielsen, Secretary of Homeland Security from 2017 to 2019. (author’s screen grab)

- ICE Agents from Immigration Nation detaining undocumented immigrants in Bronx, NY. (author’s screen grab)

- First undocumented immigrant interview on Immigration Nation. (author’s screen grab)

- Berman, Judy. “Netflix’s Searing Docuseries Immigration Nation Is the Most Important TV Show You’ll See in 2020.” Time, July 29, 2020. https://time.com/5872474/immigration-nation-review-netflix/. [↩]

- Horton, Adrian. “How Netflix’s Immigration Nation shows the true horror of ICE agents.” The Guardian, August 19, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/aug/19/netflix-immigration-nation-ice-true-horror. [↩]

- Hildreth, Matt. “Immigration 101: What is Zero Tolerance Family Separation?” America’s Voice, March 25, 2019. https://americasvoice.org/blog/separation-of-children/ [↩]

- Wanzo, Rebecca. Suffering Will Not Be Televised, The: African American Women and Sentimental Political Storytelling. SUNY Press, 2009. [↩]

- Macaya, Ángeles Donoso. “Immigration Nation (Review).” nacla, August 14, 2020. https://nacla.org/news/2020/08/14/immigration-nation-review. [↩]

- Villarreal, Yvonne. “Inside ‘Immigration Nation,’ the Netflix docuseries ICE didn’t want you to see.” Los Angeles Times, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/tv/story/2020-08-04/netflix-immigration-nation-shaul-schwarz-christina-clusiau [↩]

Defining what constitutes humane can be problematic and challenging.

However, upon the first twenty minutes of Immigration Nation, I was struck by how the docuseries does not grant the same screen time to undocumented immigrants as it does to ICE agents.

This uneven representation is just one of many symptoms of a larger problem with how the docuseries constructs and depicts undocumented immigrants’ perspectives and suffering. In this piece, I explore how Immigration Nation politically mobilizes undocumented immigrant people to investigate the state of the U.S. immigration system.

The docuseries examines immigration policies from an institutional point of view and only introduces undocumented immigrants’ perspectives as an attempt to elicit a sentimental reaction from the audience. As the daughter of two immigrants, one of whom has experienced the effects and trauma of deportation in the past, the undocumented immigrant representation in the docuseries is heartbreaking.

Yet, as a race and media scholar, I am troubled by the mobilization of undocumented immigrant suffering for sentimental political storytelling.