Transnational Chills: A History of Latinxs’ Love of Horror

Orquidea Morales / State University of New York, Old Westbury

Author’s Note: This column is the first in a three-part series that examines Latinx horror film and television. Here, I delve into the relationship between Latinx communities and the horror genre focusing on language, nationality, and generic definitions.

My relationship with horror films started at a very young age. I watch them hoping to be terrified, looking for that adrenaline rush. The first moment I remember being scared by a movie was when I was a little girl. I was watching Dr. Giggles (1992) at my aunt’s house in Reynosa, Tamaulipas in northern Mexico and the titular character’s evil cackle has been burned into my memory ever since. My aunt lived right next door to a video rental shop, so we were always watching dubbed American horror films.

Of course, I am not the only Latina in love with the genre. On the October 31st, 2015 episode of NPR’s All Things Considered correspondent Vanessa Rancaño talked about Latinos love for horror films.[1] When I first listened to Rancaño’s piece “Why Latinos Heart Horror Films” I couldn’t help but nod in agreement.

Latinxs’ love has led to big profits for horror films. A 2012 Nielsen study found that Latinxs make the highest audience share of horror/thriller film releases. This fact has held true. In the 2016 article “Scare up Success with Hispanic Horrorphiles,” Diana Rasbot notes “Hispanics are 42% more likely than non-Hispanics to be horror fans—and it’s only one of many genres enjoyed by Hispanics.”[2] Such is the power of the Latinx horror fan that the 2018 horror film, The Nun, which starred Mexican actor Demian Bichir broke box office records for the Conjuring universe thanks to Latinx audiences that made up 36% of theater goers.[3] Unfortunately, the love is not reciprocated by Hollywood. Representation of Latinxs in front and behind the camera in film continues to be significantly low. Thus, Hollywood profits from Latinx audiences yet doesn’t tell Latinx stories or include Latinx actors and creators.

In these three columns, I wrestle with a few questions: What is Latinx horror? What is the relationship between Latinx horror and Latin American horror? What role does language play in horror? This is not an attempt to answer these complex questions, but rather to fuel a conversation about this long-lasting love affair.

A logical place to start is the 1931 release of Dracula and Drácula. These two films really set the groundwork for questions we still have today.

Multilingual Draculas:

In 1931, the addition of sound was changing filmmaking in Hollywood. Many actors and actresses with accents lost roles or were no longer able to play protagonists. At the same time, Hollywood producers worried that monolingual English films would lose international audiences. Facing this conundrum, Universal Studios took a unique approach to their monster movie, Dracula.

Dracula and vampire tales are one of Hollywood’s most popular undead monsters. In the U.S. alone there have been roughly 120 films starring this monster since the release of Dracula in 1931.

The plotline is simple: Renfield, an English solicitor travels to Transylvania to meet with Count Dracula in order to help him lease an abbey in London. Dracula turns Renfield into a vampire. Renfield’s hunger for blood drives him crazy and he is institutionalized in London while Dracula looks for more victims, now in the city. His two victims are Mina and Lucy. Lucy dies, but Mina slowly starts to turn into a vampire. Van Helsing, after treating Renfield at the asylum, discovers Dracula is a vampire and hunts him down and kills him. Dracula’s death returns Mina to her human state. What is less known is that at the same time in 1931, the film was also being produced in Spanish. The Spanish version has the exact same plot with a few minor differences including the names of the female protagonists. Mina is now Eva and Lucy is Lucia.

The English language version of the film that starred Bela Lugosi in the titular role was directed by Tod Browning. At night, the same sets would be used to film a Spanish language version of the film starring Carlos Villarías as Drácula and Lupita Tovar as Eva that was directed by George Melford and Enrique Tovar Ávalos (who was uncredited for his work). Melford did not speak Spanish so Tovar Ávalos served as translator and co-director.

The films have had very different trajectories particularly when the Spanish version was considered lost. In the 1970s, a print of it was found in Cuba. Since then, Drácula has been given a new lease on life. However, what is important to note is that from very early on in the birth of the horror genre Spanish-speaking audiences were a primary concern to the Hollywood film industry.

Why are Dracula/Drácula so important for our conversation on Latinx horror? The multilingual vampires show how important Latinx and Latin American audiences have been for Hollywood. However, they also show the strange conflation between the categories of Latinx and Latin American that still happen today. For example, many Latin American audiences criticized the fact that Spanish language Hollywood films during this time had mixed accents. In the case of Drácula, Eva was Mexican while Drácula was Spanish. The lack of awareness or lack of care that these differences highlight show the continuing erasure of Latinx and Latin American differences.

The blurring of these linguistic differences aside, Dracula/Drácula show how important Latinx and Latin American audiences were for Hollywood. Scholars such as Colin Gunckel[4] and Lisa Jarvinen[5] have documented the way Hollywood saw Latin American audiences as one of their biggest consumers and saw Spanish language productions as a necessity to cultivate that audience at home and abroad.

The uneven presentation of Latinidad by Hollywood did provide crucial access for Latinx and Latin Americans interested in filmmaking. Hollywood often borrowed Latin American talent and vice versa, thereby creating a complicated and unequal transnational filmmaking history. At the same time, though, these linguistic differences and the attempt to garner audiences in the U.S. and Latin America exemplify how Latinx horror is inherently a transnational genre. No case exemplifies this better than another vampire tale, the film From Dusk till Dawn (1996) directed by Robert Rodriguez. The movie stars Salma Hayek as Santanico Pandemonium, a vampire at the Titty Twister bar on the Mexican border that entices men with her dancing. The name Santanico is borrowed from the 1975 Mexican nunsploitation movie Satanico Pandemonium-La Sexorcista. That film, directed by Gilberto Martínez Solares and starring Enrique Rocha and Cecilia Pezet, is about young Sor Maria (Pezet), the purest of the nuns living in the convent, who after encountering Beelzebub (Rocha) slowly succumbs to the temptations he sets in front of her. The name shows one small example of how Mexican horror films can and do influence the creation of Latinx horror.

I would like to conclude by going back to the story of Dracula/Drácula. Two movies I had never seen until a few years ago when in conversation about early Latinx horror with a friend the title came up. Yes, I knew of Dracula, but my mind was blown when I learned of Drácula. Now that it had seen the light of day, Drácula was a darling for scholars and fans alike. The Hollywood history was fascinating for many of us. And it served as a reminder that even though Latinx and Latin American audiences have been a financial asset for Hollywood for decades, our dollar is rarely worth access to producing our own stories.

Image Credits:

- Bela Lugosi as Dracula in Universal’s first horror film. Author’s screengrab from Dracula (1931).

- The Curse of La Llorona scared up profits in 2019 thanks to Latinx Horror Fans. Author’s screengrab.

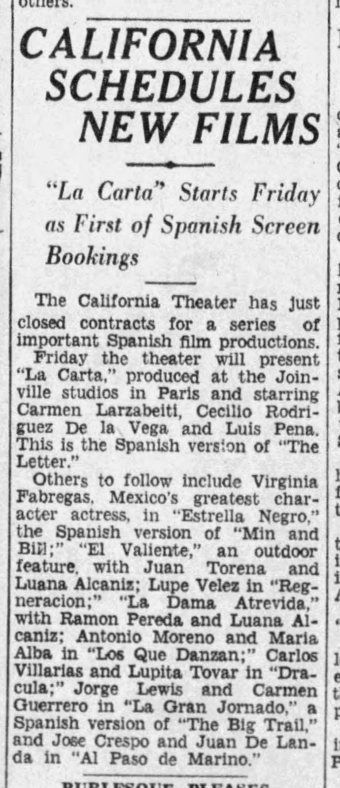

- A 1931 article published in the Los Angeles Evening Express announces upcoming Spanish language releases including Drácula. Wed, Feb 18, 1931. Page 19.

- Carlos Villarías as Drácula. Author’s screengrab from Drácula (1931).

- On the left you see young Sor Maria and on the right Santanico. Author’s screengrab from Satanico Pandemonium: La Sexorcista (1975) and From Dusk till Dawn (1996).

- Rancaño, Diana. 2015. “Why Latinos Heart Horror Films.” NPR All Things Considered. [↩]

- Rasbot, Diana. 2016. “Scare up Success with Hispanic Horrorphiles.” Univision Communications. https://corporate.univision.com/blog/2016/10/24/scare-up-success-with-hispanic-horrorphiles/ [↩]

- Hunt, Darnell, and Ana Christina Ramón. 2020. “Hollywood Diversity Report 2020: A Tale of Two Hollywoods.” UCLA College of Sciences. [↩]

- Gunckel, Colin. 2015. Mexico on Main Street: Transnational Film Culture in Los Angeles Before World War II. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [↩]

- Jarvinen, Lisa. 2012. The Rise of Spanish-Language Filmmaking: Out from Hollywood’s Shadow, 1929-1939. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [↩]

This is a really insightful piece, and something that is not often discussed. I teach a class on Mexican Cinema and we cover horror specifically during our discussion of genre due to its popularity and distinct style in Mexican filmmaking. I have always felt that horror resonates so deeply with Mexican audiences due to both the culturally specific relationship to death in Mexico and the country’s violent and traumatic history that has become ingrained in Mexican living mythology and psyche. The relationship between the living and the dead is less finite in traditional Mexican culture, and the supernatural is part of a spiritual reality that continues to flow in everyday life. One just needs to look at how many filmmakers have used La Llorona as their source material to see this. Of course Hollywood is ignorant of this context and its nuance, and to them it is simply: the Latinx audience likes horror. I am really looking forward to your next 2 pieces!

I wonder what you think of Guillermo Del Toro’s use of horror hybrid genres and how they do so well internationally? He has said that his love of horror is rooted mostly in Mexican horror films, and the filmic poetics of his movies demonstrate that. Yet, beyond his Spanish language films, he does not cast Latinx actors.

Great piece, Orquidea! Love the Spanish language Dracula quite a bit, and always use it in my Film History class when I teach about the transition to sound. I teach it in Adaptations as well, especially because as an adaptation of the novel, it has more scenes than the English language film and so is actually a more complete – “authentic” – version of the novel.

Will you be talking about the Paranormal Activity series in later essays in this series?

Keara Goin, thank you for your feedback! I’m still working through del Toro. Should we consider him a Latinx director? Latin American? Both? How does this complicate Latinx horror as a genre. Definitely something I’ll think through in my next piece when I write about transnational horror.

Dan, I’m thinking about it! I think part of Latinx horror is how audiences react to these films aimed at them. The Paranormal was definitely pandering but folks seemed to be genuinely excited about it.