In Solidarity(?): A Critique of the K-pop Industry’s Support for Black Lives Matter

Dayna Chatman / University of Oregon

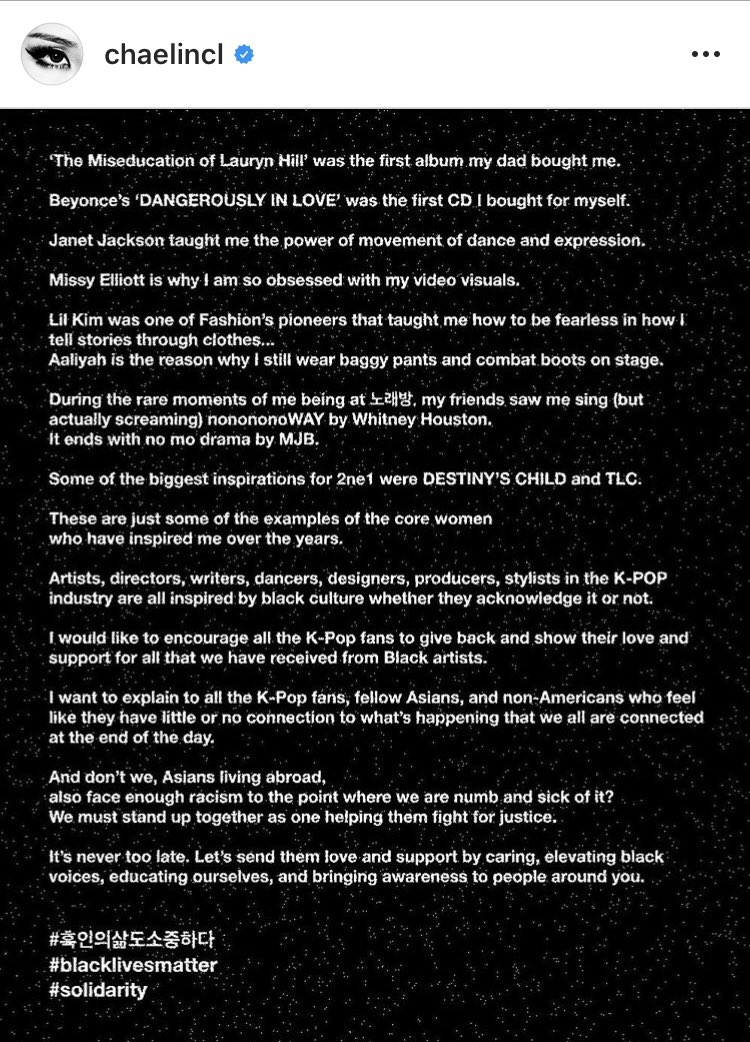

The title of this piece, “In Solidarity(?),” foregrounds a question raised by some K-pop fans in the wake of an outpouring of support for the Black Lives Movement from Korean and Korean American idols and their companies, following the murder of George Floyd. In posts on social media, idols revealed how listening to Black American music genres like hip hop and R&B influenced their interest in music. K-pop has been and continues to be heavily influenced by Black American music, dance, and performance styles (see Anderson, 2020; Lie, 2014; Song, 2019). The recognition of the connection between Black American culture, K-pop, and K-pop idols, functioned as a bridge to explain why the racial unrest happening in the US mattered personally to these artists. However, apart from this connection, how ready is the K-pop industry to reconcile its current support for Black lives with its history of signifying blackness in marginalizing ways?

K-pop fans often talk about idols confronting their “dark history” or “dark past.” These phrases function in two different senses. First, to talk about an idol’s “dark history” can refer to misbehavior in their lives before they were famous (e.g., childhood bullying, scamming people, etc.). It is also jokingly used to refer to idols reliving their most embarrassing or cringe-worthy public moments. In this latter sense, revisiting one’s dark history is meant to elicit laughs from both idols and fans. However, the expression should extend to include a reflection on those actions that have generated racialized conflicts amongst fans. At times, Black American K-pop fans find themselves traversing a music genre and fandom communities that register both appreciation for and hostility towards their culture and experiences. K-pop groups, or their companies, have been called out for the following:

- blackface performance

- cultural appropriation of Black hairstyles

- mockingly using African-American vernacular English

- using the “n-word” in songs, and

- perpetuating stereotypes that project a negative image of Black people

This post highlights examples of K-pop’s dark past, discusses Black American fans’ experiences responding to perceived racially insensitive behavior in the genre, and closes with a suggestion for what solidarity might look like within the K-pop industry and in fan communities.

Remembering K-pop’s “Dark Past”The examples I introduce in this section are illustrations of the types of things that have happened in K-pop that need to part of reckoning with the genre’s treatment of blackness. In some instances, the companies or idols did offer apologies; in others, they did not.

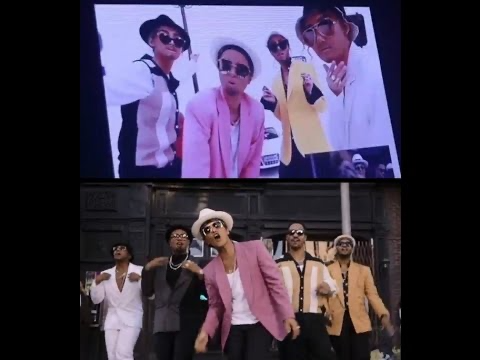

In 2017, the female quartet Mamamoo faced backlash after a photo taken at their Seoul concert was posted online. In the picture, the four members appeared dressed in suits with darkened skin and goatees drawn on their faces. They had intended to parody Mark Ronson’s “Uptown Funk” music video, which features Bruno Mars alongside Black male backup performers. The group, and their management company, Rainbow Bridge World, issued a formal apology (see Herman, 2017).

Wendy, from the girl group Red Velvet, was the subject of online criticism in 2018 after she appeared on a South Korean talk show Talkmon (tvN & O’live, 2018). Asked about different English dialects since she grew up in both Canada and the US, Wendy proceeded to mimic how white and Black girls speak. It was her impersonation of Black women, in which she snapped her fingers while making big motions with her hands, pursed her lips, and shook her head while sassily saying, “what did you say, girl?” that angered Black fans (1:30 mark in the video above). There was never any apology statement from Wendy or her agency, SM Entertainment, released.

Artists have used the “n-word” during performances when covering American hip-hop and R&B songs that use the word. In 2010, rapper Zico, from the boy group Block B, released a remake of “I’m Still Fly” originally by Big Page and featuring Drake. While he re-wrote much of the lyrics, Zico kept the chorus, which meant that he did not omit the n-word.

The single “T.O.P.” represents an example in which a boy group, Shinhwa, released an original K-pop song that used the n-word. The song appeared on the groups’ 1999 album, “T.O.P (Twinkling of Paradise), and contained an English rap verse performed by member Eric Moon. In his verse, he raps: “This is how we do it, you n****s better know / Do you want to see the light or stand alone?” As the track pre-dates the contemporary period of global visibility of K-pop, not much is known about whether it received any criticism at the time. However, when BTS did a cover performance in 2014 on the music program Show Champion (MBC M, 2012–), they did not censor the lyrics. Subsequently, there was a debate amongst fans about their decision not to.

Although fandoms can and do feel like community for individual fans, Lori Morimoto (2019) argues that they are also “contact zones”—spaces where cultures meet and clash. When Black American K-pop fans address insensitive actions in K-pop, they are often dismissed by other fans. A typical reply from non-Black fans is that Korean idols are unaware of America’s racial history (see Han, 2015). Consequently, Korean idols nor their management companies can be expected to know that someone will view their actions as offensive or harmful. This explanation may be acceptable if the K-pop industry was in its infancy, but repeated infractions throughout its history suggest that management companies and their artists have not sufficiently prepared for the global stage.

An example of a recent dismissal of Black American K-pop fans’ concerns occurred following rapper Agust D’s—known more widely as Suga from the idol band BTS—release of his second mixtape D-2 on May 22, 2020. The track “What Do You Think?” sampled a speech by Jim Jones, an American cult leader who orchestrated the mass suicide of his followers in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1979. Some Black ARMY (BTS fans) criticized the samples’ use by highlighting that Jones was a mass murder whose actions led to 900 people’s death, many of them Black. For several days, a debate raged on Twitter about artistic freedom and whether Black fans were, once again, creating a problem that did not exist. In response to fans’ debate over “What Do You Think?” Agust D’s management label, Big Hit Entertainment, stated on May 31 that producers selected the speech for “aesthetic reasons” (Hong, 2020). The company acknowledged that while they had a review process for all sampled material, they did not thoroughly vet the speech. To remedy the situation, Big Hit removed Jones’ voice and re-released the track. However, the company’s actions only momentarily curtailed the debate which was reignited following news of Big Hit and BTS’s support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

non-black armys congratulating them for doing the absolute bare minimum.. this is not enough!! and frankly it comes off as lazy and obligratory. why dont they start by addressing the instances of cultural appropriation of Black culture throughout their career and in the industry?

— yeontan’s eyebrows (@portaeble) June 4, 2020

Should the K-pop industry’s expressions of support for Black lives and racial justice in America be written off as performative wokeness? It’s too early to tell. There are some signs that the industry is at least listening to fans and empathetic to some concerns. For instance, fans expressed discontent after a promotional photo of a member from the group ATEEZ revealed a blue-dyed cornrow hairstyle. The management company for the group quickly responded with a statement acknowledging fans’ concerns and took action to ensure the member would not have his hair styled in that manner during promotions for the groups’ album (see Stich, 2020). However, in general, the industry’s track record of addressing racially insensitive mishaps is the source of some fans’ cynicism about companies’ and individual idols’ efforts to align with Black Lives Matter’s aims. Moreover, responses to present controversies do not acknowledge previous points of criticism that went ignored.

The following questions remain: Are individual idols, entire groups, or their management companies willing to reflect on how K-pop has contributed to the marginalization of Black Americans? What are they committed to do going forward to ensure the same mistakes do not occur in the future? Genuine solidarity must go beyond symbolic gestures on social media and monetary donations. It must first take the form of critical introspection. Secondly, it must manifest in the acquisition of consciousness about the markets the K-pop industry aims to reach. Absent of these actions, showcasing of support on social media amounts to window-dressing.

Image Credits:

- Rapper CL posts on Instagram about how hip-hop has influenced her. (Original IG Post here)

- Quartet Mamamoo parodying Bruno Mars “Uptown Funk.” (author screenshot)

- Wendy on Talkmon.

- Zico, “I’m Still Fly.”

- Shinhwa, “T.O.P.”

- BTS, cover of “T.O.P.”

- @Portaeble’s reply to @BTS_twt’s #BlackLivesMatter support tweet from June 4, 2020.

Anderson, C. (2020). Soul in Seoul: African American popular music and K-pop. University of Mississippi Press.

Han, G. S. (2015). K-pop nationalism: Celebrities and acting blackface in the Korean media. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 29(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2014.968522

Herman, T. (2017, March 6). K-pop girl group Mamamoo apologizes for blackface ‘Uptown Funk’ performance. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/k-town/7710346/k-pop-girl-group-mamamoo-apologizes-blackface-performance-uptown-funk

Hong, C. (2020, May 31). Big Hit Entertainment releases statement about Suga’s mixtape sampling controversy. Soompi. https://www.soompi.com/article/1403720wpp/big-hit-entertainment-releases-statement-about-sugas-mixtape-sampling-controversy

Lie, J. (2014). K-pop: Popular music, cultural amnesia, and economic innovation in South Korea. University of California Press.

Morimoto, L. (2019). From imagined communities to contact zones: American monoculture in transatlantic fandoms. In M. Hills, M. Hilmes, & R. Pearson (Eds.), Transatlantic television drama: Industries, programs, and fans (pp. 273–290). Oxford University Press.

Song, M. (2019). Hanguk hip hop: Global rap in South Korea. Palgrave Macmillan.

Stich. (2020, July 14). ATEEZ parent company KQ Entertainment issues apology for Hongjoong’s cornrows. Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/ateez-kq-entertainment-apology-cornrows-hongjoong

I had no idea… Thank you for sharing and raising such important questions. With BTS’s popularity in America I’m both surprised and not surprised it hasn’t been addressed.

This was a good read. One point “perpetuating stereotypes that project a negative image of Black people” reminded me of a post I saw some time ago on, I believe, lj. Where someone wrote that the stereotyped image is taken, mostly, from American media where Black people are portrayed as criminals and later on they/other countries go with that image. I think they also mentioned that one drama adaptation of Yori dango (or what was that cluster fuck called? Nvm), had a scene with that stereotype (I’m seriously going with my memory here and I never watched any adaptations of that manga because I hate the source material).

Also, am I the only one who think that k-pop is like “let’s use the n-word to sound so hip and cool, yeaaah!” *rolls eyes at this debauchery* Don’t get me wrong, they deserve and should be called on that shit. (And other shit too).

^ this was supposed to be tweeted but decided to comment on here.

For additional information on BTS and Big Hit Entertainment’s action towards BLM, they actually donated usd$1 million (reported on 6 June, 2020 – https://variety.com/2020/music/news/bts-kpop-black-lives-matter-hashtag-1234625436/)

ARMY matched the donation within the first 30 hours (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52960617)