All the Content, Just For You: TikTok and Personalization

Andrea Ruehlicke / University of New Brunswick

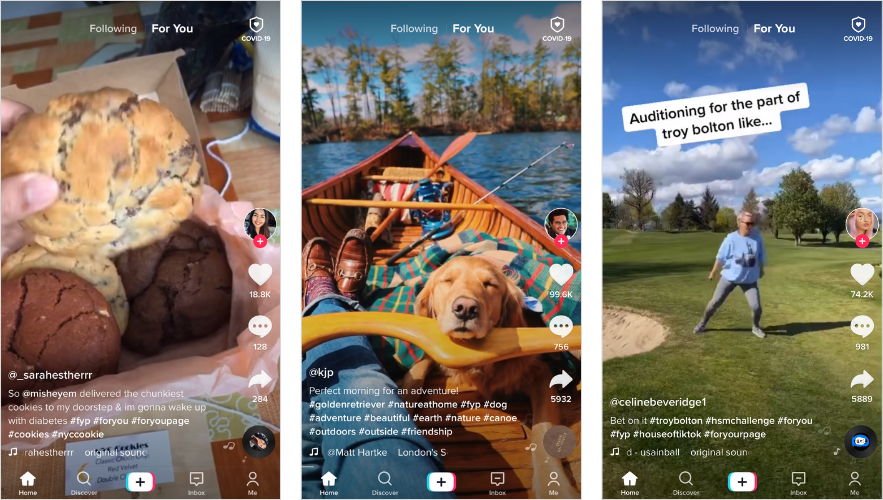

Personalization is the buzzword for most social media. Our Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook feeds are curated both by and for us. YouTube, Netflix and a host of other streaming platforms cannot wait to recommend content they are sure we will enjoy. Social media thrives on the notion that the ideal online experience is one that is tailored around the individual and their interests. TikTok extends and nuances this understanding of content made for the user. Labeling each users’ home screen as the For You Page (often shortened to FYP), the app presents itself as a tool for delivering content tailor-made for the user. TikTok uses auto-play to extend this idea and to drop the user into an endless stream of content they are assumed to enjoy. The platform represents a new development in how we think and talk about personalization in virtual spaces. Looking at some of the formats of videos lets us more easily consider how users understand the platform and how ideas around individualization impact the types of videos that get created.

While most social media platforms have the user begin from a homepage or dashboard, TikTok removes this requirement of user-initiated direction. Rather than pointing out options the user might want, these videos are presented immediately upon arrival. The app drops the user into an always playing stream. The auto-play format encourages an understanding of being known by the algorithm. While other sites suggest content, there is still a sense of control for the user. They must accept or reject the platform suggestions. TikTok bypasses this step. While the user can reject a suggestion by immediately swiping to the next video, acceptance is assumed. As soon as you open the app (and watch an ad), videos begin playing. You can confirm you enjoy the video through liking it or following the creator, but you do not have control over where you start. This auto-play also allows for playfulness in being read or misread.

The focus on personalization is viewed as the way to deliver users the most optimal experience online.[1] Not only can you find users who share your interests, the platform will create an entire experience just for you. It is important to point out that Michelle Kim and others have reported on how TikTok has faced pressure due to revelations that it was intentionally suppressing some users’ videos.[2] While feeds are assumed to be personalized, it must be made explicit that not every user and video is treated equally. This notion of extreme personalization is occasionally taken up by creators. One form of personalization is content that presumes a one-on-one relationship between the creator and the viewer. These videos tend to feature a creator staring at and speaking directly to the viewer. The example below highlights this presumed closeness. While this video is posted for mass consumption, the format suggests a much more intimate relationship between creator and viewer.

@ari.tendo even tho I’ve been learning French for 5 years ##frenchiebabyy ##passecompose ##ShowAndTell

♬ Lets Link – WhoHeem

On TikTok, it is not the user that enacts personalization. Tanya Kant reminds us, “Rather, with the help of a multitude of personal data collected by platforms as you go about your day, your needs and interests can be algorithmically inferred and your experience “conveniently” – and computationally – personalized on your behalf.”[3] Customization is provided to the user by the platform. There are few options for individuals looking to tailor the app to their desires. Instead, the individual user can be considered as a provider of data.[4] They can like videos and follow creators (and alternatively quickly skip videos that are not to their tastes). But the notion of customization on TikTok comes from having provided “enough” data that the platform and algorithm can provide videos and creators that have been tailored to one’s interests.

Personalization systems both shape and are shaped by users. While seemingly providing total control to the user, these systems also lead the user towards certain choices so as to better fit with how the system has recognized them.[5] My own experience with the platform demonstrates this push that Jonathan Cohn discusses. My own feed is heavily populated with Dungeons and Dragons and various other role-playing properties despite my non-engagement with these properties in any aspect of life. Despite my protestations, clearly TikTok believes me to be a once or future d&d player. Here we also see the opaqueness of the algorithm. Finn Brunton and Helen Fay Nissenbaum discuss what they have termed “known unknowns.”[6] Users know their data is being collected and that attention is being paid to which videos they watch in full, skip over immediately, and which videos they formally like. But they likely have no idea what data is being recorded or how those actions play out in future recommendations. For example, I can only guess how I am being read by the platform by which videos play on my FYP. Feeling misread also offers limited recourse. One can aggressively start liking content and following certain users in an effort to sway the algorithm, but there is not a surefire way to avoid spaces and genres.

The labelling of categories and subcategories of TikTok is another way this presumed personalization plays out. In the example below the creator is welcomed to BookTok. This video makes explicit the process of being sorted by the algorithm. This user is both seen as belonging in BookTok and as explicitly not belonging in other areas of the platform. Inclusivity is presented as having spaces for everyone, not that everyone is equally welcome in all spaces. Here, being properly recognized by the algorithm is presented as a sign of having found your community.

@mariahankenman Repostingso people can use the sound! I think I fixed it🤣 ##booktok ##bookworm ##books ##readersofbooktok ##readersoftiktok ##repost ##fyp ##bookshelfchair

♬ original sound – Mariah Ankenman

These communities may seem vast as in the example of BookTok but can also be far more specialized. Frog TikTok had a moment in summer 2020 with popular articles being written about the sub-genre.[7] The video below calls attention to both the ways in which the algorithm works to continually dissect your interest while also demonstrating a number of niches available to users. Here we also see a sense of the time investment required. One must demonstrate the correct interests to be read as belonging to a variety of TikTok spaces. This also takes time for the algorithm to read and place the user in these spaces. FrogTok then is not something one can stumble into immediately upon joining.

@tiasamudaa @thaddeusshafer ##############

♬ original sound – Bryan

In focusing on a personalized experience, there comes a sense of difficulty in trying to discuss trends. Similar to Eli Pariser’s notion of “filter bubbles”, users can also call attention to their own spaces on the platform. My own conversations with friends have run into the same difficulty in finding sound or format touchstones across the platform. Unless a video is directly shared with others, there cannot always be assumed understanding between users. Here we see the idea of having a very different TikTok experience than others. This duet speaks to both the ideas of being read by the algorithm and the ways that trends do not circulate to everyone. This notion of being grouped with others who share your interests is a continuation of the sense of personalization. The creator is calling attention to the presumed accuracy of the algorithm and the assumed disconnect between their personalized feed and that of their friends.

@readysetteach ##duet with @seekatlas this algorithm is bullying me ##millennial ##millenialsoftiktok

♬ original sound – aimee marshall

Taken together, these videos convey the difficulty in discussing personalization. The term is both immediately understood and difficult to precisely define. Each video included here speaks to a different aspect of the term. TikTok’s structure, use of auto-play and the self-reflexivity of creators work to extend how we understand personalization and social media platforms.

Image Credits:

- TikTok’s For You Page

- @ari.tendo’s TikTok, 8/31/20

- @mariahankenman’s TikTok, 8/16/20

- @tiasamudaa’s TikTok, 6/29/20

- @readysetteach’s TikTok, 8/27/20

- Kant, T. (2020). Making it Personal: Algorithmic Personalization, Identity, and Everyday Life. In Making it Personal. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Kim, M. (2019, December 6). TikTok Admits It Suppressed Reach of Queer, Fat, and Disabled Creators. Them. https://www.them.us/story/tiktok-suppressed-fat-queer-disabled-creators [↩]

- Kant, T. (2020). Making it Personal: Algorithmic Personalization, Identity, and Everyday Life. In Making it Personal. Oxford University Press. [↩]

- van Dijck, J. (2013). ‘You have one identity’: Performing the self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media, Culture & Society, 35(2), 199–215. [↩]

- Cohn, J. (2019). The Burden of Choice: Recommendations, Subversion, and Algorithmic Culture (Vol. 2019). Rutgers University Press. [↩]

- Brunton, F., & Nissenbaum, H. F. (2015). Obfuscation: A user’s guide for privacy and protest. The MIT Press. [↩]

- Lindsay, J. (2020, July 8). What is frog TikTok, and why does it so often cross over with lesbian TikTok? Metro. https://metro.co.uk/2020/07/08/what-frog-tiktok-why-often-cross-lesbian-tiktok-12961023/ [↩]

Nice; good work on pointing out suppression. Very informative article!

wow, good job