“It’s ARMY versus the U.S. Army”: K-Pop Fans, Activism, and #BlackLivesMatter

Laura Springman / University of Texas at Austin

On May 21, 2017 Billboard held its annual Music Award show, celebrating the top artists, albums, and songs of the year. Introduced in 2011 and voted on by fans, the “Top Social Artist” award celebrates the musical artist most engaged with their fans on social media. For the prior six years, this was awarded to Justin Beiber and he was nominated again that year. However, history was made that night when the Korean pop band BTS (Bangtan Sonyeondan, 방탄소년단) broke Bieber’s streak and became the first K-pop group to win the award, which they won again in 2018 and 2019.

Those familiar with K-pop stan’s social media presence were presumably unsurprised by this shifting tide in the social media category. K-pop stans know how to use social media and are frequently responsible for at least one of the trending topics or hashtags on Twitter. However, the content of these posts is not only about idols holding a number one spot on charts and trending. K-pop fandom more broadly has a history of activism and charitable work, something that came to the attention of mainstream media recently due to their involvement in the Black Lives Matter movement. After the recorded death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis Police circulated the internet, many took to social media sites like Twitter to express their anger and spread information about fundraisers and protests. To some, a surprising ally surfaced in the form of K-pop Twitter stans, and in particular fans of BTS known as ARMY (Adorable Representative M.C for Youth). This well-organized group of fans gained widespread recognition and appreciation for their sustained efforts to promote Black Lives Matter.

Drawing from fan studies scholar Henry Jenkins’ work on fan activism, and other scholarship on the politics of fans, I examine how ARMY continued a long practice of fan activism with their involvement in the Black Lives Matter movement on Twitter. While I agree that trending a hashtag is not enough to change the violent structures we are fighting, I argue that this social media activism matters. It should be taken seriously in an effort to fight ableist assumptions of activism and to avoid the pathologization and invalidation of feminized fandoms. Studying ARMY and K-pop fan activism facilitates important conversations around the stigma certain fandoms face, in particular Western perceptions of K-pop and their fan practices.[1] Fan studies as a discipline is no stranger to pushing back against gendered notions of value that draw lines around sanctioned fan activities and identities. With this work, I want to remove the binary discourse structuring many conversations around social media activism and fandom. Instead of seeing it as either productive or lazy, real activism or fake activism, good fans or bad fans, the reality of the situation is much more complex and nuanced. In addition, it’s important to consider the context in which these protests occurred, during a pandemic. A large number of people were unable to attend protests for various reasons specific to the pandemic and thus harnessed Twitter as a way to be involved and up to date without being on the ground.

For this article, I draw from Henry Jenkin’s scholarship on fan activism and utilize his definition of fan activism as:

Forms of civic engagement and political participation that emerge from within fan culture itself, often in response to the shared interests of fans, often conducted through the infrastructure of existing fan practices and relationships, and often framed through metaphors drawn from popular and participatory culture.[2]

Much of the previous fan activist scholarship has examined how fans of a fictional text map the content of the text onto real-world issues. In particular, a focus has been placed on organizations like the Harry Potter Alliance. In comparison, ARMY activism stems more from BTS member’s activism rather than that of fictional characters fighting against a magical enemy. So here I ask, how do we understand fan activism when it’s not through the framework of Dumbledore’s Army but instead BTS’s ARMY?

“I never thought I’d see the day where kpop stans are defeating the police and I fu***ng love it” (@blom_dot_com, May 31, 2020).

In late May and early June, it was not uncommon to see sentiments like these on Twitter, expressions of surprise and delight at K-pop stans joining the Twitter fight against the police and in support of Black Lives Matter. This particular tweet, and many others like it, were in response to a variety of K-pop fans, including ARMY, who responded to the Dallas Police Department’s “iWatch Dallas” app. Designed to encourage bystanders to submit video evidence of illegal protest activity, this app was immediately seen for what it truly was, a way to target and identify protesters regardless of their “illegal” activity.[3] In response, K-pop fans weaponized fancams. A fancam is a video that focuses on one specific idol during a live performance instead of the entire group. Instead of getting video evidence of protesters, the DPD instead found themselves sifting through countless fancams of idols. It took less than 24 hours for the DPD to tweet: “due to technical difficulties iWatch Dallas app will be down temporarily” (@DallasPD, May 31, 2020). The system of organization normally utilized to vote for one’s favorite group or idol and break music video views records was instead repurposed to mobilize fans to prevent the DPD from enforcing a surveillance culture that criminalized protesters. In addition to this, fans used an existing K-pop tradition as a vehicle for their activism, that is, using fancams as opposed to using memes or whatever else non K-pop fans might have used in their place. In response to this, other Twitter users asked K-pop stans to flood alt-right hashtags across social media sites. Fancams and K-pop memes abounded on hashtags like “ExposeAntifa,” “WhiteLivesMatter” and more, drowning out the hateful rhetoric these hashtags intended to foster.

While some found the turn from keyboard smashing over idols to politicized server jamming surprising, it’s important to remember that fandom is not a-political. In fact, for some, fandom might be their first brush with an organized community. As Suzanne Scott wrote, “while fan spaces are not always as inclusive and progressive as one may want to think, there is no denying the politicized nature of the fan and fan practices.”[4] Fandom facilitates a participatory culture and has a history of engaging people in ideological and cultural resistance to heteronormativity, patriarchy, and more.[5] It’s not a stretch to see how those involved in fan networks would utilize the same structures they use for sharing exciting BTS news, to also discuss racial politics and ways to support social movements.

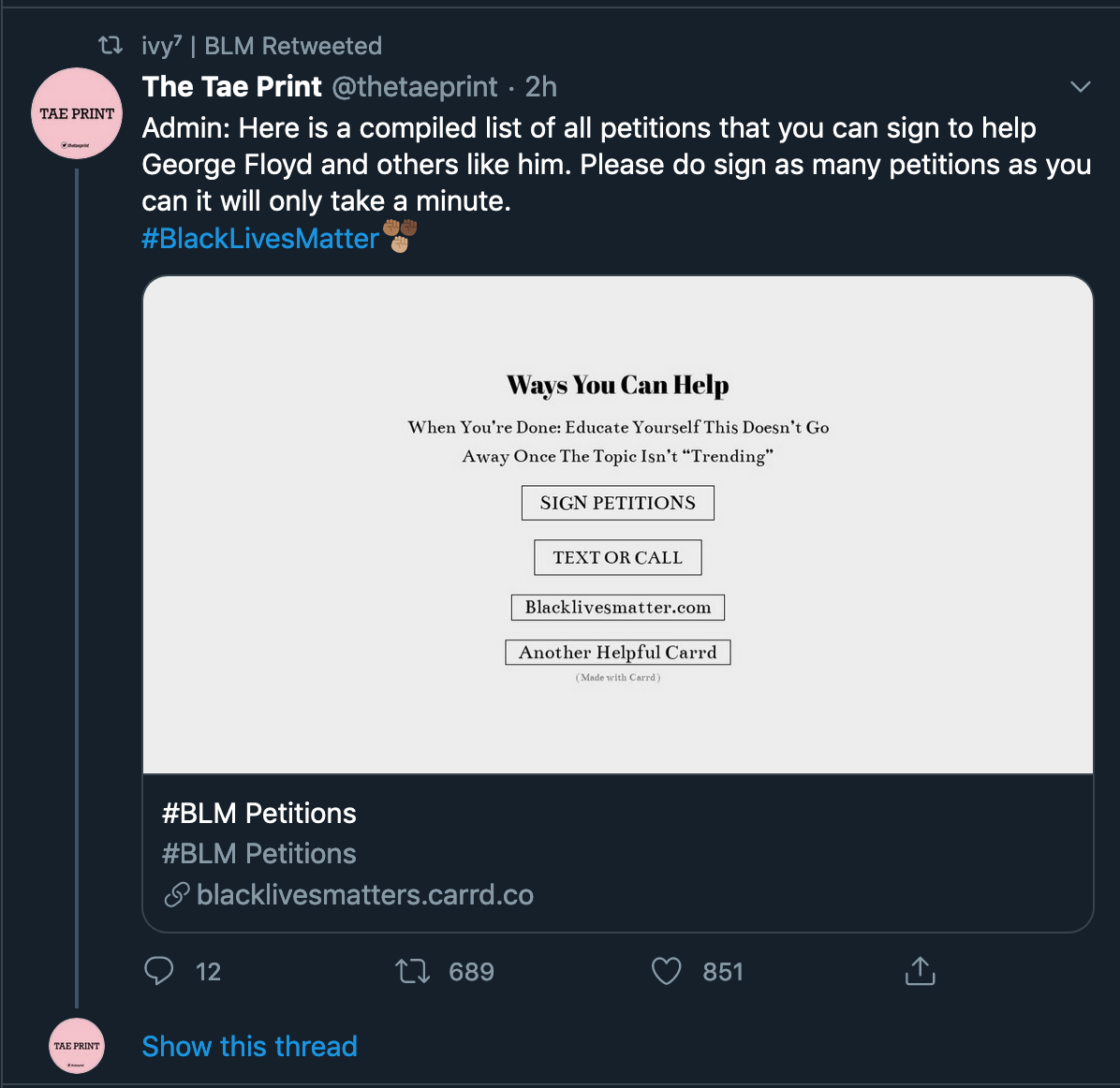

Something that hasn’t been included in mainstream coverage of this content is the micro acts of disrupting the status quo on ARMY Twitter. While not everyone might label this as activism, it is undoubtedly a form of participatory culture and a way to raise awareness of the cause, even if it’s in more micro inter-personal ways than petitioning or physically protesting. Twitter accounts dedicated to individual BTS members paused their regularly scheduled content in favor of spreading information about the protests, fundraisers, petitions, and ways people could help the BLM cause. Other personal Twitter accounts popular for their fanfiction threads chose not to update so as to not distract attention from the important social and political issues occurring.

In addition to these more individual actions, a concerted effort was made to avoid trending topics related to BTS in respect to BLM. While much of the protests and fundraising efforts were occurring, it was also an important time for ARMY. Every year an event called “Festa” happens in BTS fandom, a 10+ day celebration to honor the band’s debut in 2013. Many fans tweeted to express the importance of avoiding trending topics related to Festa and any new content released alongside the event. In particular, fans made sure to take creative steps to censor BTS’s name, using numbers instead of letters, asterisks to censor “Bangtan” (part of the band’s full name,) and specific emojis to replace individual member’s names. When BTS member Min Yoongi did a VLive to discuss his new mixtape on May 28th, fans consistently reminded one another to avoid using his name and instead use a cat emoji. In addition, they cautioned fans to refrain from posting translations in the fear they would trend, and encouraged users that wanted to post about him, to do so on Weverse instead of Twitter. As Melissa M. Brough and Sangita Shresthova touched on in their article “Fandom Meets Activism: Rethinking Civic and Political Participation,” these actions fall in line with more “informal, cultural engagement” and act as kinds of “culturally defined solidarity” that challenge our perceptions of what counts as political involvement.[6] This raises important considerations of how we understand actions that disrupt the status quo and create an environment unwelcoming to those wishing to ignore the current political climate. Perhaps these are instances of micro-activism, or better yet acts of solidarity and culture jamming.

The most well-known action on behalf of ARMY was their own donation of $1 million to organizations dedicated to Black lives in response to the band announcing their $1 million donation for the cause. The effort to #MatchAMillion was organized by @OneInAnARMY, an ARMY organization started in response to BTS’s involvement with UNICEF for their “Love Myself” campaign. Composed of ARMY volunteers, the organization has done an astonishing amount of work in just 2 years, including raising $46,000+ in just one year to fund a variety of projects including purchasing formula for babies in Venezuela, Ramadan meals for Syrian refugees, a year of basic food for LGBTQ refugees, and more.[7] Further illustrating that ARMY has long been involved in activist work, and embodying what Jenkins mentions in his definition of fan activism, ARMY harnessed their fandom’s pre-made systems of organization to mobilize for a variety of causes not directly related to BTS.[8] Just a few weeks after K-Pop fans made the news for shutting down the iWatch Dallas App, they were featured again after working with users on the app TikTok to buy tickets for Trump’s June 19th rally in Tulsa with no intention of attending, resulting in a delightfully underwhelming number of attendees. These actions have not gone unnoticed, with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeting: “KPop allies, we see and appreciate your contributions in the fight for justice too” (@AOC, June 20, 2020). This is only a taste of what I have no doubt will continue. Who knows what we’ll see next from ARMY and K-pop Twitter.

Looking at K-Pop activism opens up a host of new questions and considerations in our research of fan activism and participatory culture. How do we understand fan activism when it manifests through seemingly small actions or instances of disruption, instead of outright protest? Especially during our current pandemic climate, with people on social media more frequently than before, it’s worth considering how acts of fan activism can look like disruptions of regularly scheduled content. Fandom has never been apolitical, and the actions we see today on K-Pop Twitter stem from a history of activism and involvement on behalf of individual fans and fan networks. Especially considering BTS’s involvement in politics, philanthropy, and social commentary, we will continue to see ARMY as a force to be reckoned with, whether it’s through dominating fan votes like the BMA’s “Top Social Artist,” or by shutting down a surveillance app, donating $1 million, and flooding the timeline with anti-racist information and fundraisers.

Image Credits:

- One in An Army’s fundraiser for Black Lives Matter hasn’t ended with #MatchAMillion. The fandom is encouraging fellow ARMYs to stay involved and continue to make a difference (author’s screen grab).

- BTS ARMY: Inside the World’s Most Powerful Fandom | MTV News.

- The Tae Print, a Twitter user dedicated to updates on BTS member Kim Taehyung, interrupting their normal content to spread information on #BLM (author’s screen grab).

- A Twitter user’s censor guide for Tweeting during Festa 2020, including information on emoji use to avoid trending (author’s screen grab).

- BTS Army of fans match K-pop band’s $1 million donation to Black Lives Matter | The World ABC News Australia.

- The BTS Army Are Mercenaries for Change – Carpool Karaoke Bonus Clip | The Late Late Show with James Corden.

- Former K-pop reporter Hyunsu Yim has a wonderful thread on Twitter educating users on previous K-pop activism and the history of Western coverage of both the K-pop genre and its fans, while also highlighting dismissive coverage. https://twitter.com/hyunsuinseoul/status/1268520592354897920. [↩]

- Henry Jenkins, “‘Cultural Acupuncture’: Fan Activism and the Harry Potter Alliance,” ed. Sangita Shresthova and Henry Jenkins, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 10, Special Issue, “Transformative Works and Fan Activism” (2012), https://journal.

transformativeworks.org/index.

php/twc/article/download/305/259?inline=1?inline=1. [↩] - Dallas Police Dept (@DallasPD), “If you have video of illegal activity from the protests and are trying to share it with @DallasPD, you can download it to our iWatch Dallas app. You can remain anonymous. @ChiefHallDPD @CityOfDallas,” Twitter, May 31, 2020. https://twitter.com/DallasPD/status/1266969685532332032. [↩]

- Suzanne Scott, Fake Geek Girls: Fandom, Gender, and the Convergence Culture Industry (New York, NY: NYU Press, 2019), 29. [↩]

- Henry Jenkins and Sangita Shresthova, “Up, Up, and Away! The Power and Potential of Fan Activism,” ed. Sangita Shresthova and Henry Jenkins, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 10, Special Issue, “Transformative Works and Fan Activism” (2012), https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/download/435/305?inline=1?inline=1. [↩]

- Melissa M. Brough and Sangita Shresthova, “Fandom Meets Activism: Rethinking Civic and Political Participation,” ed. Henry Jenkins and Sangita Shresthova, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 10 Special Issue, “Transformative Works and Fan Activism” (2012), https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Melissa_Brough2/publication/259823348_Fandom_meets_activism_Rethinking_civic_and_political_participation/links/586e77b108ae329d6214071c/Fandom-meets-activism-Rethinking-civic-and-political-participation.pdf. [↩]

- “About Us,” One In An Army, accessed July 11, 2020, https://www.oneinanarmy.org/about. [↩]

- Neta Kligler-Vilenchik et al., “Experiencing Fan Activism: Understanding the Power of Fan Activist Organizations through Members’ Narratives,” ed. Jenkins, Henry and Sangita Shresthova, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 10, Special Issue, “Transformative Works and Fan Activism” (2012),https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/download/322/273?inline=1?inline=1. [↩]