Synchronizing Song and (Diegetic) Sound in Music Videos

Laurel Westrup / University of California, Los Angeles

What happens to music videos during a global pandemic? Some have taken to music video parodies and remixes to express their COVID-19 lockdown triumphs and tribulations. Others have taken the virus as inspiration for new music. Detroit rapper Gmac Cash, known for his comedic raps, brings both levity and a serious public service message to his “Coronavirus” music video. Still others have found creative workarounds. Thao & The Get Down Stay Down’s recent music video for “Phenom” took to Zoom (like so many of us) after their video shoot was cancelled. These videos are products of a remarkable time, and they certainly provide us some much needed entertainment. The Gmac Cash and Thao videos appeal to us not only through their timely content, though—they also use diegetic sound to get our attention. While the term “music video” implies the centrality of the song, diegetic sound is a typical, though understudied, component of music videos.

In my first Flow column, I suggested that the audio-visual synchronization that characterizes music videos extends beyond the presumed function of videos as advertisements for popular songs. Here, I will return to that assertion from a different angle. If music videos are expected to sell a song, then the song is what we should hear, right? While his own analyses often refuse this simplistic reading, music video scholar Mathias Bonde Korsgaard initially suggests that one of the defining qualities of a music video is that “no incisions are made in the song’s structure—the song’s length determines the video’s length.”[1] This implies that song and soundtrack are one-and-the-same, and that the song must not be altered nor non-song diegetic sounds added that might extend or interrupt the soundtrack provided by the song. In practice, though, this is almost never the case.

Music video scholars have long noted outliers that move beyond song-as-soundtrack. To take a classic example, Michael Jackson and John Landis’s Thriller (1983) incorporates multiple musical cues and diegetic sound effects, and it also rearranges the album version of the song to better center both Jackson’s dancing ability and the video’s narrative.[2] The 6-minute album version of “Thriller” incorporates some sound effects, but the 14-minute Thriller video is much more sonically complex. Relatively few music videos rework the original song and sound design as extensively as Thriller. But by treating Thriller as an outlier, we risk suggesting that most music videos simply import a pop song as soundtrack. Nearly all music videos use a song (or sometimes multiple songs) as a starting point, true, but they frequently add to and/or alter the song(s) in their sound design.

Sound design that extends beyond the commodity version of the song often serves a music video’s narrative, which may or may not extend from the song’s lyrics. For instance, while the lyrics of Logic’s “1-800-273-8255” (titled after the American suicide prevention hotline) already suggest the narrative progression of a teen protagonist from suicidal thoughts—“I just want to die today”—to hope—“I don’t even want to die today”—the video extends and deepens this narrative, in part by adding additional sound elements and rearranging the song. In “1-800,” Director Andy Hines bookends the opening and closing of the song, itself stretched well beyond its original 4 minutes, with the cooing sounds of a baby and a man singing a lullaby. In the first scene, a father (Don Cheadle) comforts his baby son. Over the course of the music video, his son (Coy Stewart), now a teenager, struggles with his sexuality and almost commits suicide, in part because of his father’s rejection. The last scene sees father and son reconciled, and we hear the adult son singing to his own child. The cooing and lullaby sounds are integral to the video’s narrative structure as the main character’s near-tragic story comes full circle.[3] These additional sounds deepen our engagement with the video’s diegetic world beyond the basic narrative of the song’s lyrics.

Throughout “1-800,” Hines finds transitional moments in the song (i.e. between verse and chorus) where musical elements can be extended, reworked, or muted to make space for narrative expansion. We see and hear a similar, though perhaps less seamless example of this in Hayley Kiyoko’s “Girls Like Girls” music video, where at a natural break in the original song a little before 3:00, the song becomes muted for the dramatic climax of the video, where the two girls consummate their attraction in a kiss and one of the girls fights the other’s abusive boyfriend. In this case, while the lyrics of the song suggest an attraction between female friends, and perhaps even a boyfriend who’s in the way, the video elaborates on this narrative, and the additional dialogue and diegetic sound during the muted segment of the song provide space for this extension.[4]

Diegetic sound need not be focused on narrative development, though. It can also be musicalized so that it augments both the story world and the song. Unlike “1-800” or “Girls Like Girls,” Lil Nas X’s “Panini” includes only the faintest whiff of narrative. Nonetheless, the futuristic world of the video is vivid, both visually and aurally. Throughout the video, diegetic sounds like Lil Nas X’s rocket boots landing on an airplane wing and the crackle of a hologram screen add sonic punctuation to the song. As in Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” video (released 30 years prior), diegetic sound also conveys the embodied experience of dance, in this case rendering the robot dancers more “real,” as we hear the sounds of their bodies in motion.

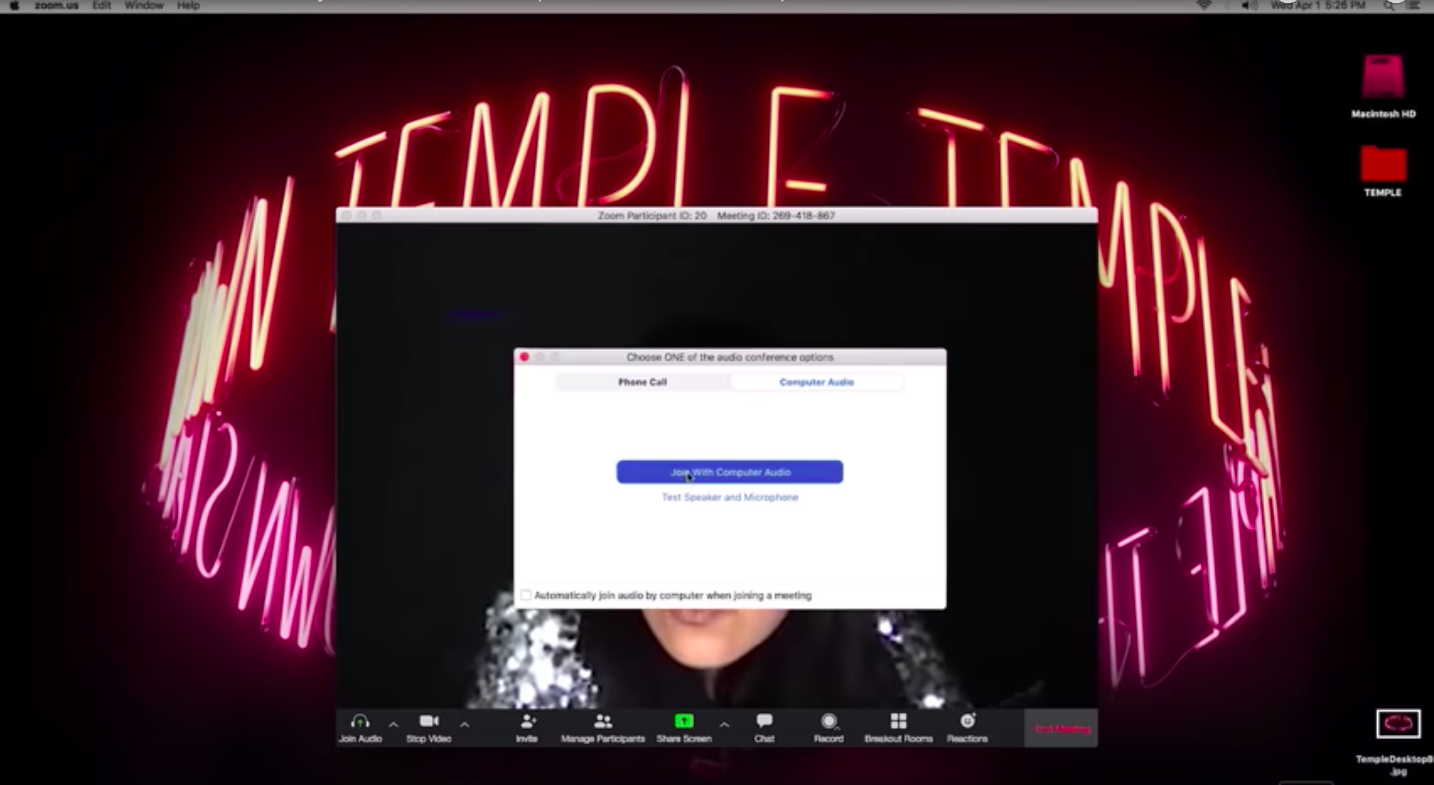

In all of the videos I’ve discussed thus far, the diegetic sounds are quite noticeable. But sound design can play a more subtle role in integrating song and story in music videos. Take the example of “Phenom.” Like “Panini,” “Phenom” is not explicitly a narrative music video. It does have a narrative frame, though: Thao is at her computer, connecting with friends via Zoom. We not only see her screen at the beginning of the video, but we also hear her click on “new meeting” and then “join with computer audio.” These quotidian sounds might seem unremarkable, but they do a couple things for us as listeners. First, they give us a moment to take in the video’s context, and to recognize the visual Zoom interface. Second, these clicks give the song, once it starts, a sense of intimacy. In listening to the song, we seem to be listening to the track along with Thao on her computer. She’s sharing her sound with us as well as with her friends. This is important since, as Thao told The Verge, “At first we didn’t know if we would even release the song [during the Coronavirus pandemic] because it’s about people unifying.”[5] The sense of connection so central to the song is signaled not only lyrically or through the cleverly choreographed Zoom dance routine, but also through the simple clicks through which Thao shares her audio with us.

The use of additional—non-song—sound in “Phenom” is not as obviously about story-telling as are some of the other examples I’ve discussed, and yet the clicking we hear can clearly be considered diegetic sound. It is part of the video’s simple story world, in which friends get together on Zoom to commune and create art. This sound is subtle, but effective. In a time where so much is changing by the minute, I find this simple gesture—to music video conventions as well as our shared story of isolation and connection—comforting.

Image Credits:

- Thao Nguyen of Thao & The Get Down Stay Down enables computer audio in the group’s recent Zoom-inspired music video, “Phenom.” (author’s screengrab)

- While Thriller (1983) incorporates non-song score and diegetic sound effects, it’s neither the first music video to broaden the music video soundtrack nor particularly unique in this regard. (author’s screengrab)

- In Logic’s “1-800-273-8255,” director Andy Hines extends and rearranges several elements of the original song as well as incorporating additional diegetic sound to tell the story of a troubled teen. (author’s screengrab)

- In Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” (1989) and Lil Nas X’s “Panini” (2019) musicalized diegetic sounds render bodies in motion more real. (author’s screengrab)

- Mathias Bonde Korsgaard, Music Video After MTV: Audiovisual Studies, New Media, and Popular Music (New York, Routledge, 2017), 26. [↩]

- I have previously argued that Thriller’s sound design plays a key role in claims for its consideration as a short film (rather than a music video), though I think it functions as both. In keeping with Landis’s and Jackson’s framing of the project as film, I have italicized it here. See my “The Long and the Short of Music Video,” The Projector: A Journal on Film, Media, and Culture 16, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 19–35, https://www.theprojectorjournal.com/past-issues. [↩]

- For a more extensive analysis of this video, see my “Listen Again: Music Video’s Cinematic Soundscapes,” in The Oxford Handbook of Cinematic Listening, ed. Carlo Cenciarelli (forthcoming, Oxford University Press). [↩]

- While we might assume that an artist would not want the integrity of their song disturbed by the type of sound design I describe here, Hines was encouraged by Logic to develop the video for “1-800” in the way he did, and Kiyoko is listed as co-director on “Girls Like Girls.” For more on working relationships between musicians and directors, see my previous Flow column. [↩]

- Qtd. in Dani Deahl, “How Thao & The Get Down Stay Down Made a Music Video on Zoom” The Verge, April 8, 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/8/21213608/coronavirus-zoom-music-video-thao-and-the-get-down-stay-down. [↩]