A Streaming Comes Across the Sky: Peak TV and the Fate of Nostalgia

Siobhan Lyons / Macquarie University

The last decade witnessed an obsession with nostalgia unseen in previous decades. A seemingly infinite list of reboots and revivals of ’80s and ’90s television, from Dallas to Full House, Roseanne to Twin Peaks, as well as ’80s-themed shows including Stranger Things and American Horror Story: 1984, have been enormously popular not only for their novelty, but also due to the ease of access that streaming platforms have afforded contemporary audiences. This longing for the past has become symptomatic of the “presentless” landscape of contemporary culture. No other culture has been able to archive itself so swiftly or had so much access to older films and television shows via Youtube and internet streaming.

Yet ironically, the very act of streaming—a paragon of binge-watching—has had an unprecedented impact on the very nature of nostalgia itself; the plethora of options given to audiences today through streaming, what has come to be known as “peak TV,” has in turn reframed the media landscape to focus on tailored entertainment, which has, in effect, destabilized the experience and formation of nostalgia.

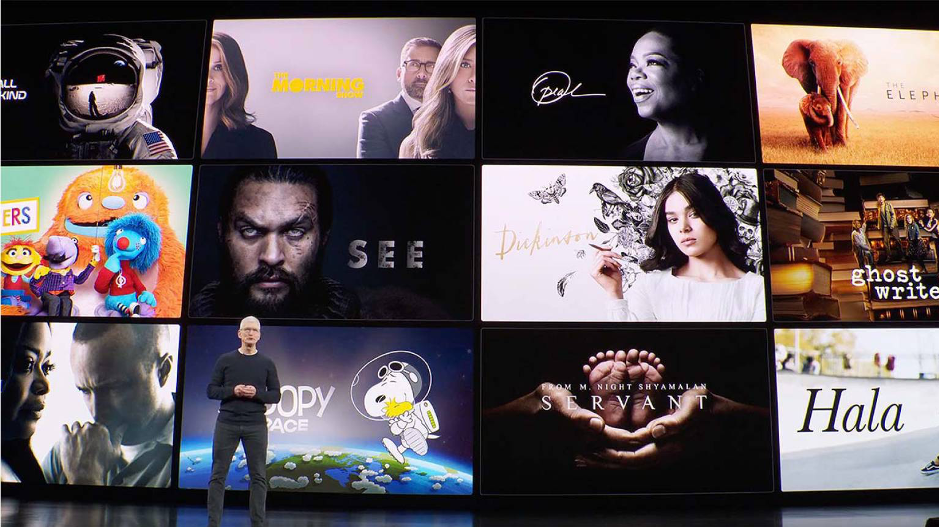

From Twin Peaks to Peak TV“Peak TV” was termed by FX Chief John Landgraf in 2015 to describe the saturation of television shows that were “drowning us in content.”[1] This trend skyrocketed in the ensuing years. In November 2019 alone, Apple TV+ released four drama television shows (For All Mankind, The Morning Show, See and Servant) followed by a fifth in December (Truth Be Told). Twenty more original programs have since been ordered. As an over-the-top (OTT) service, Apple TV+ bypasses broadcasting, cable, and satellite and operates exclusively through the internet, creating a viewing experience that also bypasses time and space, fragmenting audiences as a result.

Although both Netflix and Apple TV+ emphasize “original programming,” the sheer number of shows has had a troubling impact on the nature of viewing itself. As Catherine Bouris puts it: “Every week brings new TV shows you ‘have to’ watch, every day brings more hype on social media for yet another show you’ve just got to add to your list.”[2] She describes her television viewing experience today as less a form of entertainment or relaxation and more of a “job”: “I’m overwhelmed by the sheer number of TV shows being produced, I’m overwhelmed by the pressure I’m placing on myself to watch every ‘must see’ TV show.”

Kelly Lawler of USA Today writes that Apple TV+ and Netflix are in effect “ruining” TV:

There’s just too much TV. There was too much in 2018 and 2017, too, and probably even before 2015, when FX chief John Landgraf, coined the term “Peak TV” to describe the then-400+ scripted TV shows on the air. This year, there are more than 500. And that doesn’t count reality shows, talk shows, documentaries and everything else.[3]

In contrast, television programming in the mid to late twentieth century was confined to a set number of television shows that allowed audiences and fan bases to form more organically, allowing shows from The Sopranos to Game of Thrones to distinguish themselves. While a few streaming programs have managed to secure notable fan bases in the last few years, such as Stranger Things and BoJack Horseman, the influx of television shows is such that it makes it difficult—if not impossible—to replicate the kind of “golden era” television viewing of previous decades, in which fewer shows were embraced by larger audiences.

The effect is twofold, with the inundation of television shows leading to a more fragmented viewership, which, in turn, is diminishing the formation of nostalgia as something directly related to the shared experience of watching television.

From Communal to “Niche Nostalgia”Nostalgia—first termed by Johannes Hoffer in 1688 and described as a psychological “disease”[4]—is both a personal and shared phenomenon. The kind of nostalgia culture witnessed throughout the 2010s was fostered by the shared viewing of the rebooted shows in their heyday, from The X-Files to Twin Peaks. The broadcast medium—which inculcated both patience and longing—ensured the formation of a substantial audience and fan base from which nostalgia could successfully grow. Cliffhangers and mysteries from “Who Shot J.R.?” to “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” were embraced as communal narratives. As John Hartley points out:

Broadcast TV proved to be better than the press, cinema or even radio at riveting everyone to the same spot, at the same time—in fear, laughter, wonderment, thrill or desire. Television’s emblematic moments—the shooting of J.R. Ewing in Dallas or J.F. Kennedy in Dallas; the moon landings; the twin towers; Princess Diana’s wedding and funeral; the Olympics and football World Cup finals—the cliffhangers, weddings, departures and finales gathered populations from across all demographic and hierarchical boundaries into fleetingly attained but nevertheless real moments of “we-dom.”

Dhiraj Murthy argues that “these events were discussed for days and months afterwards and became part of the cultural memory for a generation of American television watchers.”[5] These moments have considerably lessened with the advent of streaming platforms, which have radically altered the experiential nature of television to the point where there is no longer the same sense of communal nostalgia.

In the late twentieth century, broadcast television was defined by a significant sense of community, by the limitations of the broadcast medium that forced audiences to be in a certain place at a certain time. Reruns and videos became the only means of watching a missed episode, which often meant that families or friends would be watching a finite number of programs together.

The 2010s and 20s, in contrast, have such an overabundance of content that the ability for communal nostalgia to form in the first place is in a state of flux since tastes and choices are so divided. While this may mean that tastes are much less homogenous than they used to be, it also potentially signals the demise of the nostalgic experience in television as facilitated by group fandom. As Paul Hiebert argues, it’s conceivable that “for coming generations the feeling of nostalgia might eventually disappear—not due to over-exposure or diminished effect, but because of its inability to form in the first place.”[6]

While many contemporary viewers are, of course, watching and bonding over similar shows, there is nothing that guarantees our viewership experiences are entirely shared like they used to be since there is a lower concentration of viewers for any one show. As Brian Raferty asks: “Years from now, when we finally gaze back at the pop highlights of this modern age, will any of us even be looking in same direction?”[7] He claims that “future waves of nostalgia will focus less on specific pop-cultural explosions, and more on the technologies that allowed them to spread. That’s partly because it’s never been easier to tune out the mass culture, making shared moments all the more rare.”

Streaming culture has encouraged fragmented, isolated consumer habits that limit the ability for a decade to formulate its own zeitgeist in the same way as the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s did. As Dev Allen argues: “The mainstream has split into a thousand different subcultures which is practically impossible to track.”[8] Discussing the 2010s, he says: “What would a 2010s throwbacks even look like?,” further observing that “there’s no such thing as a zeitgeist anymore.”

Amanda D. Lotz observes that while television retains significance, it does so by “aggregating a collection of niche audiences.”[9] By extension, television also creates and promotes niche nostalgia, whereby nostalgia increasingly becomes an isolated, tailored experience. Not only does this mean that there will be fewer moments of “we-dom,” as Hartley puts it, but the absence of this sense of “we-dom” will have a corresponding effect on our ability to formulate a distinct cultural character that would form the basis of future nostalgia.

Image Credits:

- Entertainment Weekly and TV Guide promoting Twin Peaks and The X-Files in the ‘90s

- Apple CEO Tim Cook unveiling new lineup of shows for Apple TV+

- Time and People Magazine speculating on J.R.’s shooter in Dallas

- Joy Press, “Peak TV Is Still Drowning Us in Content, Says TV Prophet John Landgraf,” Vanity Fair, August 3, 2018, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/08/peak-tv-fx-john-landgraf-tca-donald-glover-chris-rock [↩]

- “There Are Too Many ‘Must-Watch’ TV Shows And We Need To Start Being More Picky,” Goat, May 27, 2019

https://goat.com.au/tv/there-are-too-many-must-watch-tv-shows-and-we-need-to-start-being-more-picky/ [↩] - “Too much: Why the streaming wars between Apple, Disney, HBO and more are ruining TV,” USA Today, November 14, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/tv/2019/11/14/disney-plus-apple-tv-plus-streaming-wars-ruining-tv/2516655001/ [↩]

- Julie Beck, “When Nostalgia was a Disease,” The Atlantic, August 14, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/08/when-nostalgia-was-a-disease/278648/ [↩]

- Dhiraj Murthy, Twitter: Social Communication in the Twitter Age (Cambridge: Polity, 2013) 35. [↩]

- Paul Hiebert, “Will the Web Kill Nostalgia?,” Pacific Standard, March 31, 2015 https://psmag.com/environment/not-unless-we-invent-a-time-machine [↩]

- Brian Raferty, “Enjoy the Early-’00s Nostalgia Wave—It Might Be the Last Revival,” Wired, May 24, 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/05/the-future-of-nostalgia/ [↩]

- Dev Allen, “Why Nostalgia Could End with the ’90s,” Now This Nerd, August 28, 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PCvzfOj8spk&list=LLCbbhgGkmTNgJm9VrBT_8DA&index=42&t=0s [↩]

- Amanda D. Lotz, The Television Will Be Revolutionized (New York: New York University Press, 2014) 34. [↩]

Pingback: Adolescence: Netflix’s Prestige. – Posts