Network(ed) Spectatorship: Nation, Nostalgia, and Broadcast Streaming on CBS All Access

Cara Dickason / Northwestern University

In 2014, CBS became the first broadcast network to launch its own online streaming service, CBS All Access. Three years later, the service began streaming original scripted content only available online. CBS All Access is what Amanda Lotz has termed a “studio portal,” a vertically-integrated distribution platform that only streams proprietary content.[1] CBS has regularly been the highest-rated network, so its early foray into over-the-top subscription service illuminates how the rise of streaming may not represent a break with TV’s past but an adaptation of its conventions for new technological affordances. Turning to the network’s programming allows us to examine different conceptions of television spectatorship at play in the shift from an advertiser-based mass media model to a subscriber model reliant on the surveillance of individual users. As a spinoff of the successful CBS series The Good Wife (2009-2016), the CBS All Access series The Good Fight (2017-present) proves a uniquely fruitful case study for considering what happens to network narratives and their networked audiences as they enter the streaming wars. In its nostalgia for mass media and the unified nation it was imagined to address, The Good Fight demonstrates the ambivalent adaptation of broadcast traditions for streaming technology.

The broadcast era of the mid-20th century embraced what Anna McCarthy calls “the ‘cozy functionalist fantasy’ equating the television audience and the nation.”[2] The TV audience constituted a national public, engaged in civil discourse through the cultural forum of broadcast.[3] Today, the idea that any one television show or network is addressing anything close to the entire nation simply does not apply the way it did fifty years ago, but if anything constitutes mass media these days, it is CBS. CBS’s consistent ranking as the highest-rated broadcast network recalls that imagined national audience as opposed to the niche audiences of cable or streaming.

But the launch of CBS All Access changes the valence of that mass audience. When the platform was first announced, CBS emphasized its new “direct-to-consumer” relationship. Streaming technology allows CBS to engage less in the mass broadcast strategies of its traditional television stations, and more in what Lotz calls “mass customization.”[4] Not only is content time-shifted, but different viewers have different experiences of the portal as ads and recommendations are tailored to each individual user. In this model, television audiences ostensibly shift from members of a demographic group sold to advertisers to individual users grouped and micro-targeted by interest.

The data surveillance afforded by streaming allows those “interests” to be meticulously and individually tracked, through clicks, views, likes, purchases, or retweets. Individual interests thus come to replace the notion of the public interest. The public interest standard of broadcast television—the idea that broadcast uses public airwaves and so must operate in the public interest, convenience, and necessity—still exists, though it has only been very loosely interpreted and enforced for much of television history. However vague, though, the public interest implies the presence of a public addressed by network television, a collective body to be collectively engaged. So what happens to this national public when broadcast adopts a streaming model of individualized experience and address? What happens when you go from mass media to mass customization?

Well, according to The Good Fight, all hell breaks loose. The streaming series formally and narratively theorizes these changes in television technology, delineating a new model of television spectatorship in the streaming age. In fact, it directly critiques the use of micro-targeted content and bemoans the state of media today—in particular, the deleterious effect of the internet on public discourse. The streaming series looks nostalgically back to that “cozy functionalist fantasy” of a national public hailed by television, expressing a deep ambivalence about its own industrial and technological context.

One major character arc is lawyer protagonist Diane Lockhart’s (Christine Baranski) slow descent into madness brought on by the election of Donald Trump and the havoc he wreaks on the nation. This descent into cultural and political chaos is closely tied, in this series, to a rapidly changing media landscape characterized by ubiquitous data surveillance, the anonymity of the internet, and the isolation characteristic of digital spectatorship. The show suggests that the proliferation of digital networks in our lives has made us unable to participate in anything like a functioning national public. Our communication has broken down completely despite our many digital connections.

Instead of traditional shot-reverse-shot dialogues, The Good Fight frequently uses head-on medium close-ups, isolating and decontextualizing the speakers, to visualize our failure to communicate meaningfully. The same technique is employed to visualize internet trolls’ hateful online comments and to capture the spirit of an in-person political catfight. We understand that people are not really speaking to each other, but confrontationally shouting opinions into a void—a void occupied by us, the streaming television viewer, who has no way to participate (except, perhaps, to yell back at our screens). In an episode that features a case resembling the story of Aziz Ansari’s sexual misconduct, for instance, the camera cuts back and forth between characters looking into the camera, yelling about whether it was just a bad date or something more sinister. The editing makes clear that no one is listening to each other. There are no reaction shots, no civil discourse.

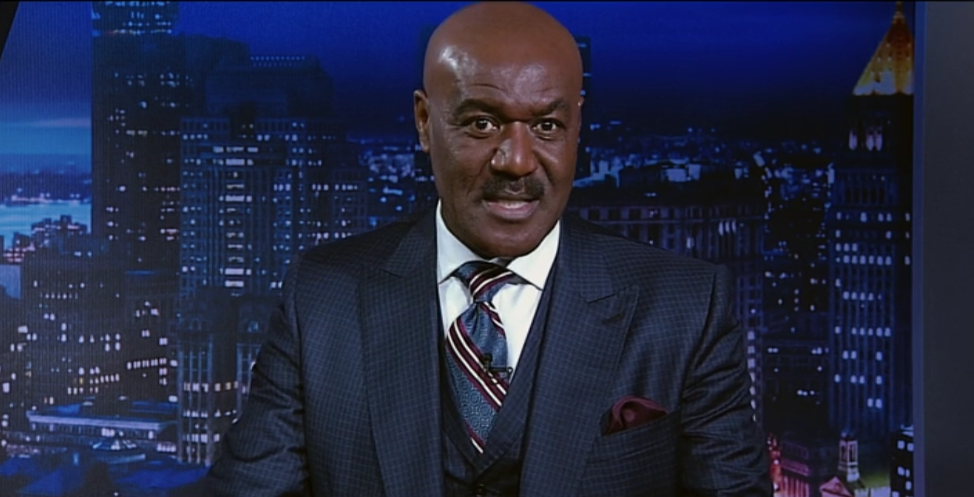

The series explicitly ties this version of (mis)communication to television culture. When another lead character, Adrian Boseman (Delroy Lindo), is a guest on a news talk show, he appears as a talking head via satellite. He sits in an empty room to film his part, and we cut between this view of him alone and a closeup on the camera lens trained on him. We know he is looking at nothing, not knowing who he is speaking to. We see the whole interview only hearing Adrian’s side, hearing his responses to questions but not the questions themselves. It all unfolds in a decontextualized rush, and only later do we learn that his interview has gone viral, being taken up in ways he never anticipated. Television itself is contributing, then, to this isolating mode of address, dangerously exacerbated by a meme culture characterized by decontextualization. Adrian’s TV interview looks just like the internet trolls’ comments, even if the content of their speech is different.

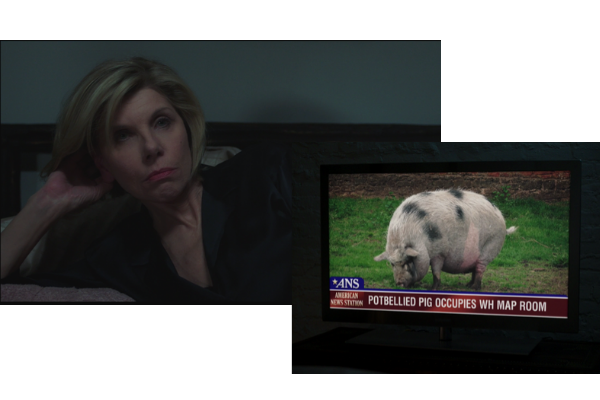

The mirror image of Adrian alone in a room filming a TV interview is the individualized television spectator, consuming media on her mobile screen. And the series emphasizes the dangerous effects of the individual targeting and consumption of media. Throughout the series, we see Diane watching television alone, often in her darkened bedroom with a glass of wine, or sometimes at work on her laptop screen. In multiple scenes, Diane flips from channel to channel, unable to escape the chaos of America’s political and entertainment systems as she encounters increasingly absurd news items, narrative television, and even weather reports. In one instance, she flips from news that Trump has tweeted something childish at a Middle Eastern leader, to a warning for Tropical Storm Don Jr., to a nature documentary identifying a plant as covfefe originalis—a reference to one of Trump’s most notoriously incomprehensible tweets. Another time, she has to ask coworkers if they heard the news about the pot-bellied pig Trump is keeping in the oval office, checking whether or not she has literally gone insane.

Her inability to tell what is real and what isn’t comes from the fact that she is watching alone, with no guarantee that anyone else is watching the same thing. Similarly, micro-targeted content, based on pervasive data surveillance, reaches only those people it may be able to convince, and so my experience of CBS All Access might be totally different from my neighbor’s. We may be digitally networked together by our access to the streaming platform, but with no common media ground, we don’t exist in the same public. The nation addressed by CBS, the broadcast network, has disintegrated into “dividuals,”[5] defined and divided by our data.

The Good Fight seems to want to remedy this problem, as it stages dialogues about social issues, thematizing and critiquing people’s inability to communicate across lines of party, age, or gender. The Good Fight thus expresses a deep nostalgia for the mass audience imagined by the broadcast television of old. That fantasy of audience-as-nation, however, always served as an excuse to ignore and erase the complex differences that nation contained—a sort of inverse to the problem of algorithms creating divisions we can’t see past. Trapped between the fantasy of broadcast’s mass media past and the dystopia of mass customization, The Good Fight struggles to identify a way forward while CBS All Access works to have it both ways. As spinoffs, reboots, and franchise IP continue to overpopulate streaming platforms like CBS All Access, Disney+, and Peacock, we’ll have to keep looking longingly backward to understand the future of streaming.

Image Credits:

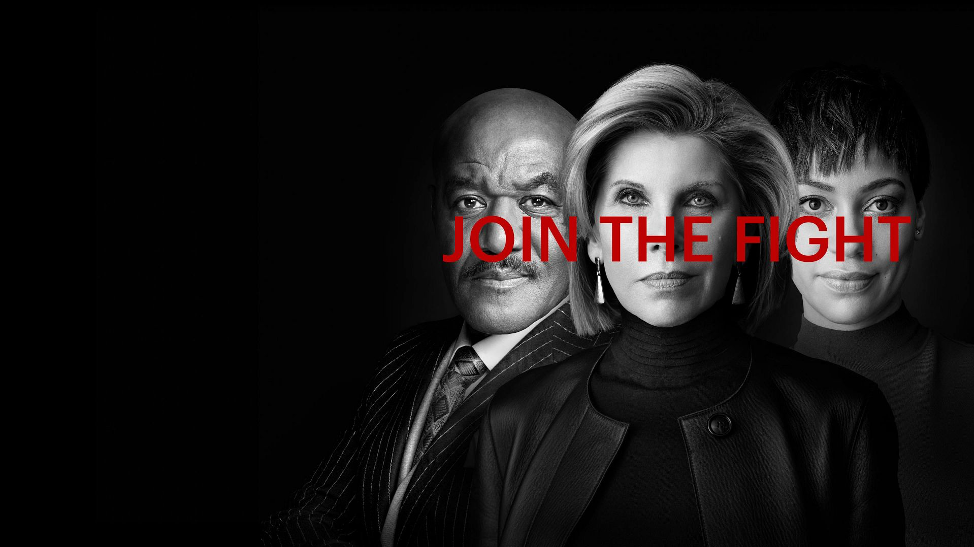

- CBS All Access showcases familiar faces in this promotional banner. Promotional image for CBS All Access. Variety, “CBS All Access on the Streaming Wars to Come: ‘We Don’t Fear These Changes.’” 1 Aug, 2019.

- A promotional image for The Good Fight on CBS All Access hails audiences to join the side of reason in our increasingly chaotic and irrational world.

- A 2014 press release for CBS All Access emphasizes the “direct-to-consumer” nature of the new service.

- An internet troll delivers his hateful comments to the screen in The Good Fight. Still from “Social Media and its Discontents,” The Good Fight (author’s screenshot)

- Adrian Boseman (Delroy Lindo) films his talking head interview for a news program alone in The Good Fight. Still from “Day 443” The Good Fight (author’s screenshot)

- In The Good Fight, Diane Lockhart (Christine Baranski) watches TV alone in her room, encountering increasingly absurd news items. Still from “Day 422,” The Good Fight (author’s screenshot)

- Lotz, Amanda D. Portals: A Treatise on Internet-Distributed Television. Michigan University Publishing Services, 2017. [↩]

- McCarthy, Anna. The Citizen Machine: Governing by Television in 1950s America. The New Press, 2010, 9. [↩]

- Newcomb, Horace M., and Paul M. Hirsch. “Television as a cultural forum: Implications for research.” Quarterly Review of Film & Video 8, no. 3 (1983): 45-55. [↩]

- Lotz, 9. [↩]

- Deleuze, Gilles. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October, vol. 59 (Winter 1992): 3-7. [↩]

really thanks for the info dear. You will get 100% best nordvpn mod apk

Cara Dickason’s work, Network(ed) Spectatorship: Nation, Nostalgia, and Broadcast Streaming on CBS All Access, provides an insightful analysis of how streaming services like CBS All Access evoke national nostalgia by blending traditional broadcast television with modern digital platforms. Her exploration of spectatorship highlights how media consumption shifts with technology, while still maintaining connections to familiar, nostalgic cultural narratives that resonate with viewers on both individual and collective levels.

Solar Prices Pakistan is a reliable and up-to-date platform providing detailed information on solar energy solutions and prices in Pakistan. We guide our users with the latest solar panel prices, installation costs, and the benefits of solar energy systems. Our website offers comparisons between local and international solar brands, helping you choose the best options. If you’re looking to install solar power for your electricity needs in Pakistan, our website offers the most accurate and relevant pricing and installation details.