Rethinking the Legacy of MVPDs Through Content Aggregation

Mike Van Esler / University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh

With the recent launch of Disney+ in November 2019, AppleTV+ in December 2019, and the forthcoming releases of HBO Max and Peacock in 2020, the subscription video on demand (SVOD) market has reached a point of saturation. All of these are in addition to existing services from Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, Pluto TV, and numerous other niche platforms. With a surfeit of digital video offerings, consumer eyeballs (and dollars!) will be jockeyed for by numerous media conglomerates, as research has found the average American consumer is willing to pay between $17 and $27 for SVOD services (Bond).

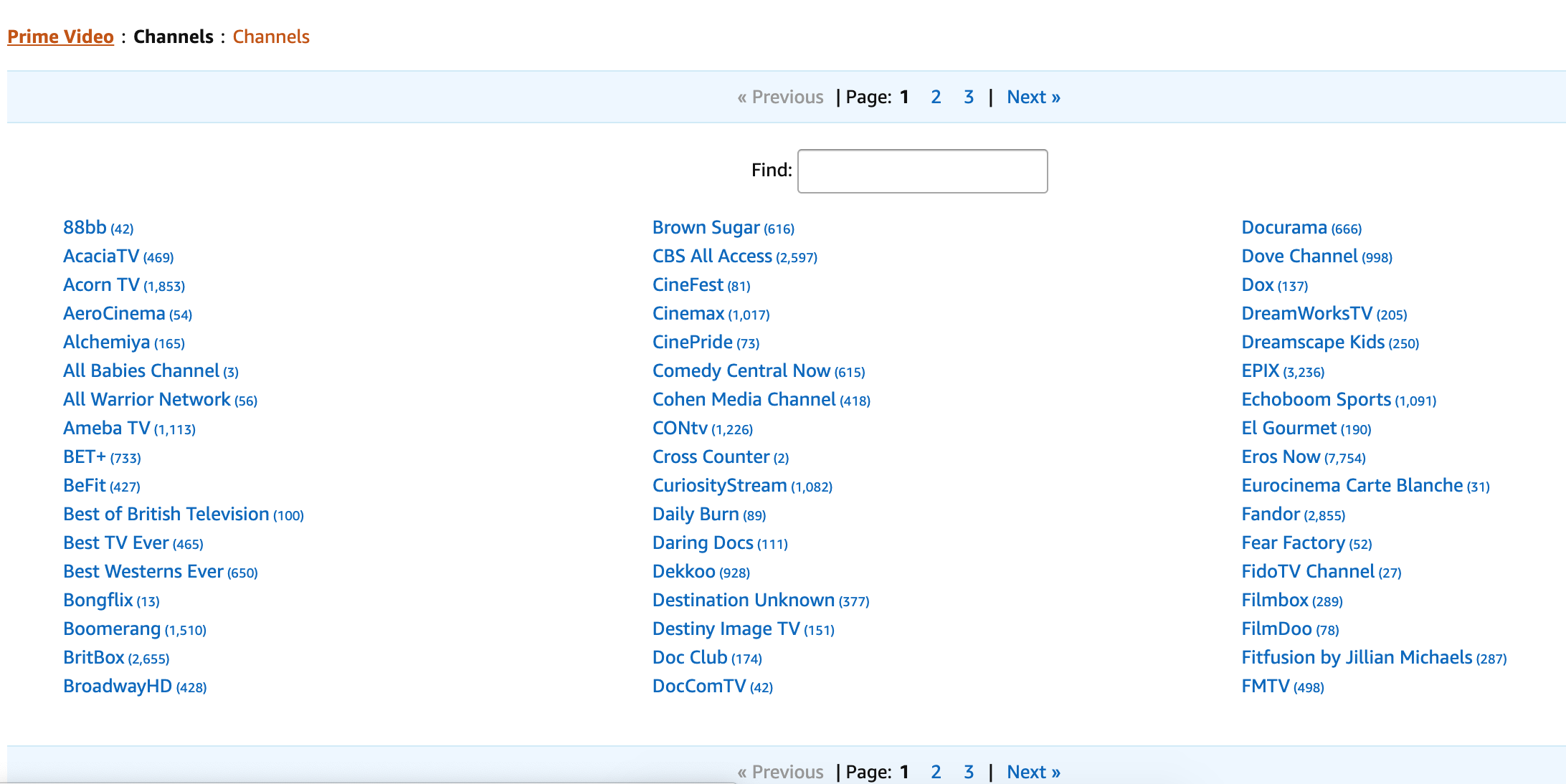

Such a relatively small amount of money to split between streaming services suggests competition will be fierce, and academic and popular press coverage of SVOD often focuses on this competition in terms of subscriber growth and the financial health of each platform. There is an alternative way to consider the economic and cultural impact of SVODs, however, one that looks backwards to a previous era of televisual “disruption.” Using Amazon Channels as a case study, I consider the economic opportunities offered by content aggregating services like Amazon Channels, The Roku Channel, and Apple TV. Put simply, content aggregation services allow users to subscribe to a wide variety of cooperating SVOD services through the connected device’s parent company, rather than subscribing to each service and then accessing it through their Roku, FireTV Stick, or Apple TV, for example. The benefit to consumers is that it simplifies billing and subscription processes, letting Amazon or Roku handle the subscription procedure and consolidating the monthly bill. Some SVOD services also offer slight discounts to those who subscribe through content aggregators, although that is not the norm.

One ongoing debate within the streaming media industry is whether content is king or if it is more lucrative to own a distribution platform. Rather than dwell in the content/platform ownership binary, I believe content aggregation is a third component, a component that sits on top of (to use digital television lingo) the platforms and content to which users are subscribing and watching. Functioning as content aggregators offers supraplatforms the opportunity to augment their parent companies’ revenue streams by collecting rent from users who subscribe to SVOD services through the content aggregation service.[1] In other words, aggregators like Amazon Channels function as emergent manifestations of the residual industrial logics of multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs, i.e. cable and satellite providers). Considered holistically, content aggregation services offer three benefits to their owners: they provide an ancillary revenue stream with minimal overhead, they help build the parent company’s brand by offering multiple sources of premium content alongside natively-branded content, and they embed users in the supraplatform’s ecosystem by tying all subscriptions to one platform.

The first beneficial aspect of content aggregation for owners of supraplatforms is the ancillary revenue stream. While Amazon draws a significant amount of revenue from its Amazon Prime subscriptions, those subscriptions also provide users with free 2 day shipping and access to Prime Video, functioning essentially as a loss-leader. With Amazon Channels, however, there is minimal overhead and each cut Amazon takes from handling the outside subscription is mostly net revenue. In 2018, Amazon Channels generated $1.8B in revenue, while in 2019 the service is estimated to have earned $2.6B (Frankel 2018; Patel 2019). With Amazon taking 30% of each subscription, Amazon generated $500M from serving as an SVOD clearinghouse. Similarly, Roku’s advertising and subscription revenue is projected to be around $433M in 2019 (Benes 2019).[2] While this revenue is dwarfed by Amazon’s total portfolio, in the context of the streaming landscape it is noteworthy, as companies like Netflix continue to operate in the red while aggressively expanding their operations internationally and spending lavishly on original productions. In other words, content aggregation services offer supraplatforms a stable revenue flow without the costly expenditures of content production/acquisition, marketing, and platform build-out.

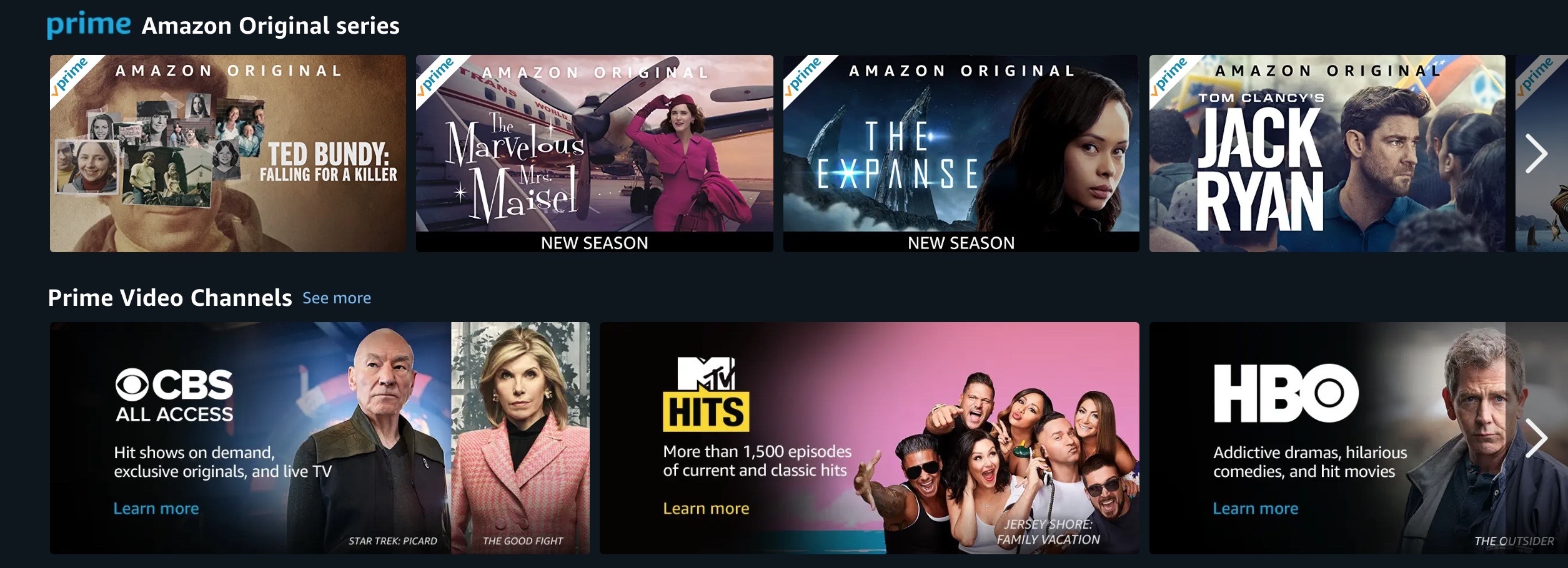

The second advantage content aggregation offers supraplatforms is brand enhancement. While a company like Amazon already has a very strong brand, their SVOD brand is muddled in comparison to Netflix or Disney+’s. This is partly due to Amazon’s strong retail branding, its relative lack of noteworthy original productions, and an overwhelmingly large library of movies that lack a cohesive ordering (Schomer 2019). What Channels offers Prime Video as a brand is a shift towards serving as a hub of premium content from services like HBO, Showtime, Cinemax, BritBox, and MUBI among many others. In this way, users will now see and have access to high profile programming like Game of Thrones (2011-2019), Homeland (2011-2020), Succession (2018- ), The Sopranos (1999-2007), and Midsomer Murders (1997- ) alongside critically-acclaimed native programming like Transparent (2014-2019) and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (2017- ). Put another way, Prime Video benefits from prestigious programming sitting alongside its House content without having to pay for production or marketing. There is a risk of brand confusion among consumers, but with Prime Video’s already-muddled brand, the tradeoff is worthwhile (a company like Apple may be more at risk with their nascent SVOD service).

Keeping users sutured into the supraplatform’s ecosystem is the final opportunity offered by content aggregation, combining the first two benefits by potentially increasing revenue via increased advertising sales and individual purchases (Amazon regularly intersperses titles available for rental or purchase among Prime content), as well increasing brand awareness by confining the user to the supraplatform. When accessing an SVOD platform like Netflix, Disney+, or HBO Now via a standalone subscription, users will be transported to a different environment, one not controlled by the supraplatform. Supraplatforms thus lose out on potential sales and advertising revenue. However, if users consolidate their subscriptions via one aggregator, they are then much less likely to leave the supraplatform for the standalone SVOD channel. Thus, for SVODs whose original productions lag in terms of brand power, content aggregation can provide a subtle but meaningful boost.

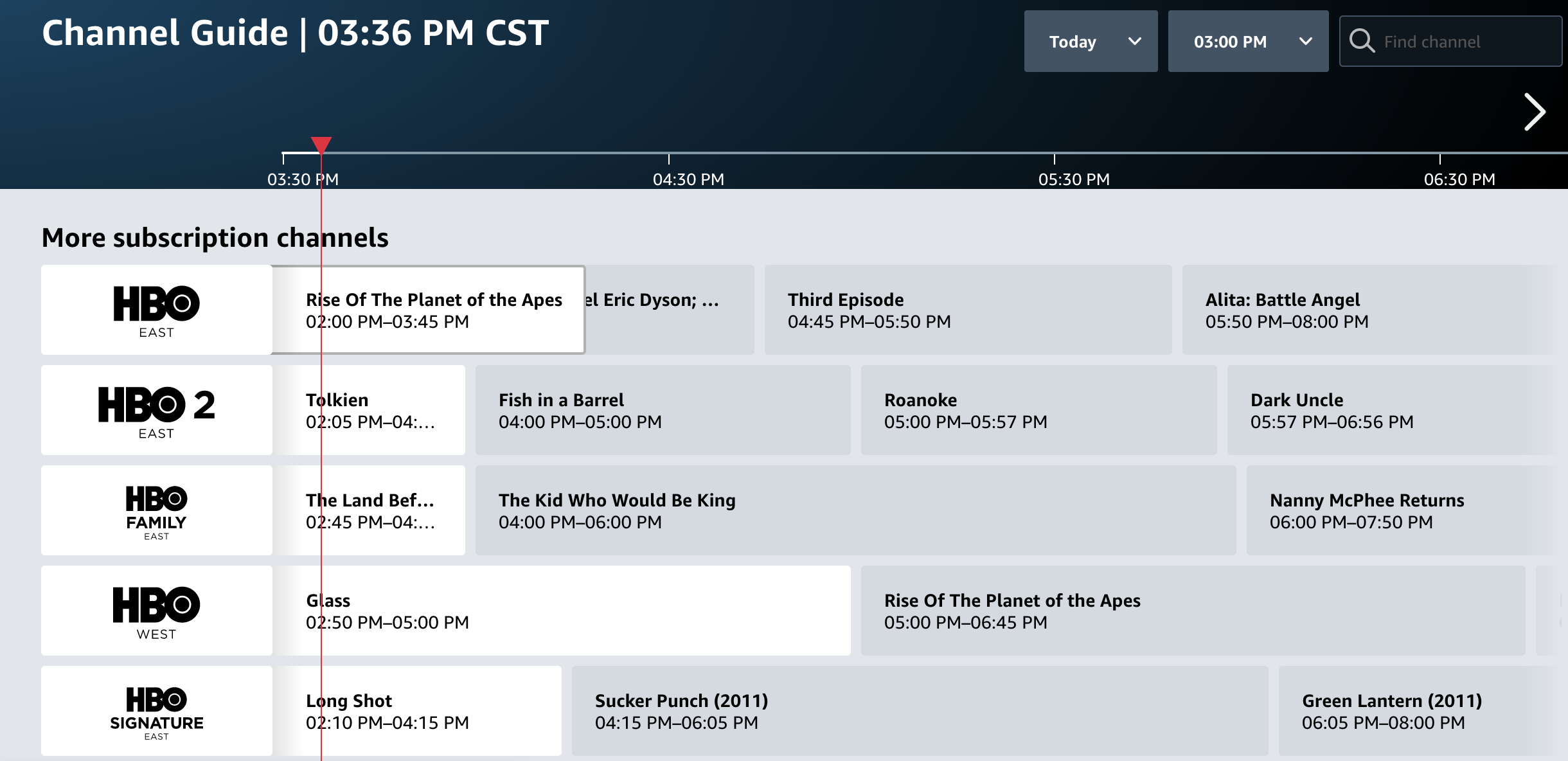

Furthermore, by consolidating the bill and different SVOD services, content aggregators are adapting the legacy industry logic of MVPDs. While there are not set packages like those of MVPDs, the creation of an á la carte bill with individual channels is functionally similar, as is the disbursal of revenue collected from subscribers (essentially carriage fees, although there are important differences). Drawing from Raymond Williams (1977), these are residual manifestations of past dominant practices in an emergent technomedia system. This is of relevance to media scholars because the constant refrain from popular and industry press has been the ongoing “death of television,” or at the very least, the death of cable and satellite. While it is true MVPDs have been hemorrhaging subscriptions in the past five years, this narrative ignores the shift to broadband as the cable industry’s major revenue stream (and associated media properties in an era of extreme consolidation), as well as the resilience of dominant industry logics to adapt to contemporary technological, cultural, and economic conditions. Indeed, content aggregation is a perfect example of this adaptation (Amazon even calls its service Channels!) and it should complicate the narrative of cultural and economic disruption caused by streaming writ large.

As Amanda D. Lotz has argued, television distributed via the Internet should not be expected to totally replace legacy forms of distribution (2017, 16); rather, the affordances of Internet distribution will build on existing industry logic and norms. Content aggregation services are one form of emergent practice that nevertheless have stark parallels with past MVPD packaging practices. By offering ancillary revenue streams with minimal costs, enhancing the supraplatform’s brand by intermingling prestigious televisual and filmic content with the parent company’s own productions, and embedding users into a single digital media ecosystem, content aggregation offers an attractive third position in the traditional distribution/content ownership binary.

Image Credits:

- Amazon Channels juxtaposes Amazon Original content with hubs to cooperating SVOD services. (author’s screen grab)

- List of cooperating SVODs available for subscription on Amazon Channels. (author’s screen grab)

- Amazon’s aptly named Channels service parallels the industrial logics of MVPDs. (author’s screen grab)

Benes, Ross. “10 Ways Roku is Growing Its Ad Business.” eMarketer,16 Jan. 2019.

Bond, Paul. “Americans Want to Pay $21 for All Their Streaming Services Combined, Poll Finds.” The Hollywood Reporter, 24 July 2019.

Frankel, Daniel. “Amazon’s Channels to Generated Estimated $1.7B in 2018.” Multichannel News, 10 Dec 2018.

Patel, Sahil. “Video Briefing: Amazon and Other OTT Channel Resellers Want Percentage of Revenue, Not Costs.” Digiday, 13 Feb. 2019.

Schomer, Audrey. “Amazon Prime Video is Suffering from a Diluted Brand Identity.” Business Insider, 31 July 2019.

Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1977.