The Reflexivity of Rigged Ratings: Nielsen in our Cultural Memory

Jennifer Hessler / Bucknell University

During the rituals of small talk on public transport or at social events, when I share that my job involves conducting research on television audience analytics—or, the Nielsen ratings—I often receive anecdotes, particularly from older generations, about how their neighbors used to be a Nielsen Family or the time their favorite television show was cancelled due to low ratings. During these interactions, the central role that Nielsen occupies in our cultural memory of television becomes readily apparent; the mere phrase “the Nielsen ratings” seems to evoke a deep-rooted nostalgia for television’s past among those who lived it.

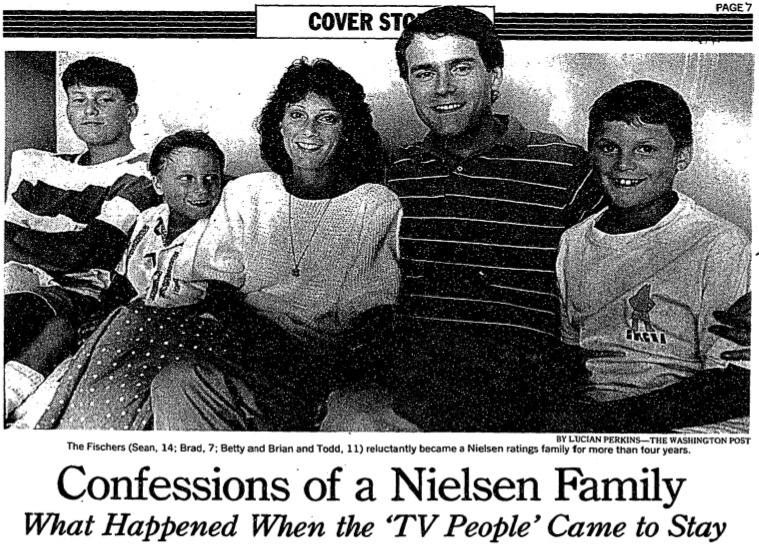

Nielsen’s place in the popular imagination started to materialize in the mid-1960s, when the industry’s increasing reliance on ratings and the well-publicized criticism of Nielsen’s methods stimulated the popular press’ interest in the “mystical band of families” who determine which television shows live or die.[1] In 1965, CBS Reports aired the first televised feature on ratings panelists, turning the Nielsen Family into “the medium’s foremost celebrity off screen.”[2] Throughout the next two decades, newscasts about Nielsen Families were commonplace, often depicting panelists as capricious, and drawing out panelists’ “confessions” about how they (unintentionally or purposefully) mis-recorded their viewing data.[3] As the Nielsen Family was becoming an icon of American televisual culture, these stories about unreliable panelists cultivated a popular imagination of the ratings that was latent with skepticism.

This image of the ratings as dubious was further perpetuated through fiction, where the vast majority of depictions of the ratings have, curiously, entailed plotlines about the ratings being rigged. In the made-for-TV movie The Ratings Game (dir. Danny DeVito, Showtime, 1984), Vic DeSalvo (Danny DeVito) is told by executives at the fictional network “MBC” that his pilot Sittin’ Pretty will only remain on air if it can beat its time-slot competitor, the World Series, in the ratings. With the help of his girlfriend Francine (Rhea Perlman), who is a statistician at the fictional ratings firm “Computron,” DeSalvo steals the complete list of “Computron” panelists’ home addresses, invites them on a “free cruise,” and then hires mobsters to break into the panelists’ houses and tune their televisions to Sittin’ Pretty. Accordingly, DeSalvo’s series gets a 60 share in the overnights and numerous accolades until his scam is discovered and he is arrested.

In television plotlines, it’s often the panelists themselves who rig the ratings. In “Prime Time,” Alf (NBC, 1987), the Tanners are chosen to be a “Tomson” ratings family, using the industry’s new “people log” meter. Immediately the family alters their viewing behaviors, tuning into informational programs like The MacNeil/Lehrer Report (PBS, 1983-95). But when Alf (Paul Fusco) discovers that his favorite show, Polka Jamboree, is about to be cancelled due to low ratings, he sets out to rig the ratings, calling 1000 households and convincing them to watch the show. When the Tanners find out about the stunt, daughter Lynn (Andrea Elson) exclaims, “Even 2000 people wouldn’t increase the ratings that much!” Alf answers, “Aha! …Unless they were each given a number and logged into the Tomson rating system,” which he follows with an obscure explanation of how he “hooked up the ratings box to the transmission on [his] spaceship, then shifted into sideways.”

In “Couch Potatoes,” Roseanne (ABC, 1995), the Conner family is likewise selected to be a Nielsen Family. After installing their ratings box, the Nielsen representative asks the Conners to verify some demographic details, explaining that “advertisers not only like to know how many people watch certain programs, but also what type of people they are.” Roseanne (Roseanne Barr) asks, “And what type of people are we?” to which the representative replies, “You’re a fine type of people, like many of the people from this type of neighborhood: large households, modest income, required education only.” After the representative leaves, Roseanne exclaims, “Can you believe that, Dan? They think we’re dumb hicks. They just want to hook up some poor uneducated slobs, so the country has somebody to blame America’s Funniest Home Videos on….We are not going to watch nothing but PBS, and the Discovery Channel, and that other smart crap. We’ll show them.” The Conners spend the majority of the episode watching nature programs in effort to appear more cultured to Nielsen and to prove that they can adopt a more “sophisticated” lifestyle.

More recently, the episode “Ratings Guy,” Family Guy (Fox, 2012), follows the same pattern of the Griffin family being chosen as a Nielsen Family. After discovering that being a ratings panelist grants him influence at his local news station, Peter Griffin (Seth MacFarlane) decides to steal all of the Nielsen boxes in order to have power over all of television. With hundreds of Nielsen boxes hooked up to his television, Peter is able to influence television executives to implement nonsensical ideas such as concluding the ad campaign pitches on Mad Men (AMC, 2007-15) with lightsaber fights, effectively ruining television and inciting an angry mob.

These narratives about rigged ratings serve as a liminal space for television writers to contend self-reflexively with their own frustrations about the ratings. The shortcomings of Nielsen’s sampling methods are a reoccurring theme. In the aforementioned plotlines, the ratings’ reliance on a very small (albeit statistically representative) number of households is what leaves them vulnerable to being rigged. Uniquely, “Prime Time” comments specifically on Nielsen’s controversial adoption of the people meter (which the episode fictionalizes as “the people log”). In an effort to learn more about the ratings, Alf watches a television interview with NBC president Brandon Tartikoff, where he is asked about the effects of the people log on ratings trends. Tartikoff gives a rambling response culminating in his assertion that “the most consistent aspect will be the total lack of ratings consistency, which is strangely enough, consistent with what we found to be an overall inconsistency.” This theme of inconsistency also manifests in relation to the ratings households themselves, who without fail end up strategically altering their viewing behavior once they become panelists. Finally, in addition to perpetuating the idea that the television industry will bend to the will of the ratings without regard to quality, the collective resolution of these episodes tends to be that the homeostasis of commercial television will always come back to a wasteland of limited story formats—such as when Peter Griffin ultimately “fixes” television by instructing executives to create fifteen workplace comedies and multiple repeats of Law and Order.

But beyond offering a reflexive outlet for television writers’ frustrations with Nielsen, the thematization of rigged ratings leans into the public’s skepticism toward the ratings, while simultaneously positioning dubious data as a necessary element of a populist media system. In other words, the Nielsen ratings’ fallibility is a result of their necessary reliance on the public’s participation in the ratings process. Ien Ang makes a similar argument when she says that “the ‘problem’ that viewers are not [panopticon] prisoners but ‘free’ consumers [sic] accounts for the limits of audience measurement as a practice of control.”[4] But what Ang does not account for is the way that the media has mythicized the maverick viewer as a rhetorical mechanism to reframe participation in audience surveillance as interactive (or even empowering) rather than disciplinary. For the viewer, alongside the skepticism they provoke, these televisual depictions perpetuate the fantasy that by subjecting one’s viewing to surveillance, one can relinquish their role as passive consumer and instead assume the role of influencer or cultural maverick.

While the Nielsen ratings have historically had a unique ontological identity, occupying a central role in our cultural memory of television, today audience measurement is almost indistinguishable among the array of consumer data exchanges that characterize the digital media landscape. Like many emblems of our television history, the Nielsen ratings (in their traditional form) are becoming archaic. In this way, these televisual narratives about rigged ratings serve as valuable time capsules—remnants of the tumultuous process of ritualizing surveillance, in part through its entrenchment in our televisual leisure, as a normalized aspect of our entertainment culture.

Image Credits:

- Profiles of Nielsen Families became commonplace in the popular press around the mid-1960s. Todd Allan Yasui, “Confessions of a Nielsen Family: What Happened when the ‘TV People’ Came to Stay,” Washington Post, 27 December 1987, author’s screengrab.

- News featurettes turned the Nielsen Family into an icon of television culture, while also highlighting their unreliability. “The MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour” PBS (News Hour Productions), aired 30 October, 1986 (American Archive of Public Broadcasting, ID: cpb-aacip/507-xg9f47hr1r).

- The Ratings Game (dir. Danny DeVito, Showtime, 1984).

- “Prime Time,” Alf (NBC, 1987).

- “Couch Potatoes,” Roseanne (ABC, 1995).

- “Ratings Guy,” Family Guy (Fox, 2012).

- Lawrence Laurent, “Memo Shows Nielsen as Wary of Probers,” Washington Post, 29 March 1963, A10; “Ratings Majors Sign FTC Consent Order,” Broadcasting 7 January 1963, 1, 66; Frank Mankiewicz, “Waiting for Rain: Down the Tube with Arbitron,” Washington Post, 5 June 1977, 244; Todd Gitlin, Inside Prime Time, revised edition (London: Routledge, 1994) (originally published in 1983). [↩]

- “The Ratings Game,” CBS Reports (CBS), aired 12 July 1965; Jack Gould, “TV: Nielsen Viewers Bear Big Load,” New York Times, 16 July 1965, 55. [↩]

- See for example, Hal Humphry, “Where Duty Lies for Nielsen Family,” Los Angeles Times 1 June 1966, C14; Jack Gould, “TV: Nielsen Viewers Bear Big Load,” New York Times, 16 July 1965, 55; Todd Allan Yasui, “Confessions of a Nielsen Family: What Happened when the ‘TV People’ Came to Stay,” Washington Post, 27 December 1987, TV 7; “Segment 3: The Ratings,” NBC Nightly News (NBC), 8 November 1977 (Vanderbilt News Archive, #491660), accessed 27 March 2019; “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” PBS (NewsHour Productions), aired 30 October, 1986 (American Archive of Public Broadcasting, ID: cpb-aacip/507-xg9f47hr1r), accessed 14 January 2020. [↩]

- Ien Ang, Desperately Seeking the Audience (New York: Routledge, 1991), 87. [↩]

I love NIELSEN family profiles and the pull they had at that point of time in market.