Market Commentary: Teaching Capitalism

Kit Hughes / Colorado State University

I get a weekly email from a financial planner that I met once years ago, when I was trying to figure out how to transition from graduate student to salaried faculty member. The fine print indicates that the newsletter, self-described only as “Market Commentary,” is the work of Carson Coaching, a company serving “growth-minded advisors” with resources they can pass off to clients. Out of inertia and perverse curiosity about what the finance industry wants to tell me about the economy, I haven’t unsubscribed.

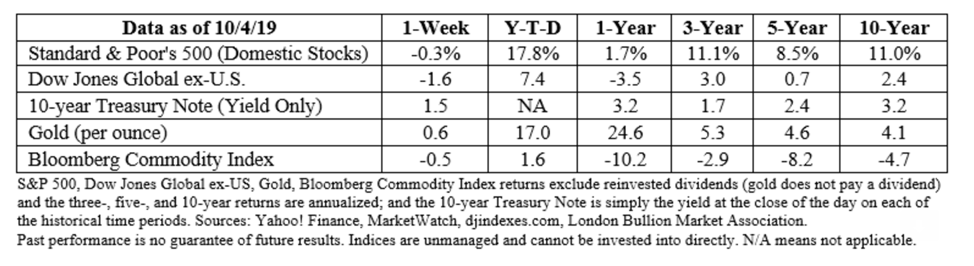

A clippings service drawing from Barron’s, The Economist, and even Yahoo! Finance, what’s interesting about the letter isn’t the ideological leanings of its reportage, which reflects capitalist orthodoxy in its discussion of bears and bulls, bond markets, trade wars, growth, and charted yields. Nor is it the conclusion of each newsletter, an inspirational “Weekly Focus” quote that susses out paeans to self-reliance from all corners. Instead, what’s interesting about this newsletter is its routine insinuation that individuals (that I) could actually do anything with this information.

A particularly banal example of participatory finance’s “extensive popular pedagogy,” the junk mail cluttering my in-box provides readers the “appear[ance of]…a stake in the capitalist financial system.”[1] Alongside investment shows and Millennial-friendly savings apps, it offers an “invitation to live by finance”—an increasingly pervasive call to develop the self through market activity and market-based logics of accounting applied to all domains of life.[2]

This process of “financialization” was built on structural changes to policy that broadened possibilities of participation in financial markets. What I want to address here is how these changes, in turn, were made meaningful by a series of mid-century New York Stock Exchange-sponsored films designed to introduce mass shareholdership as an American way of life.

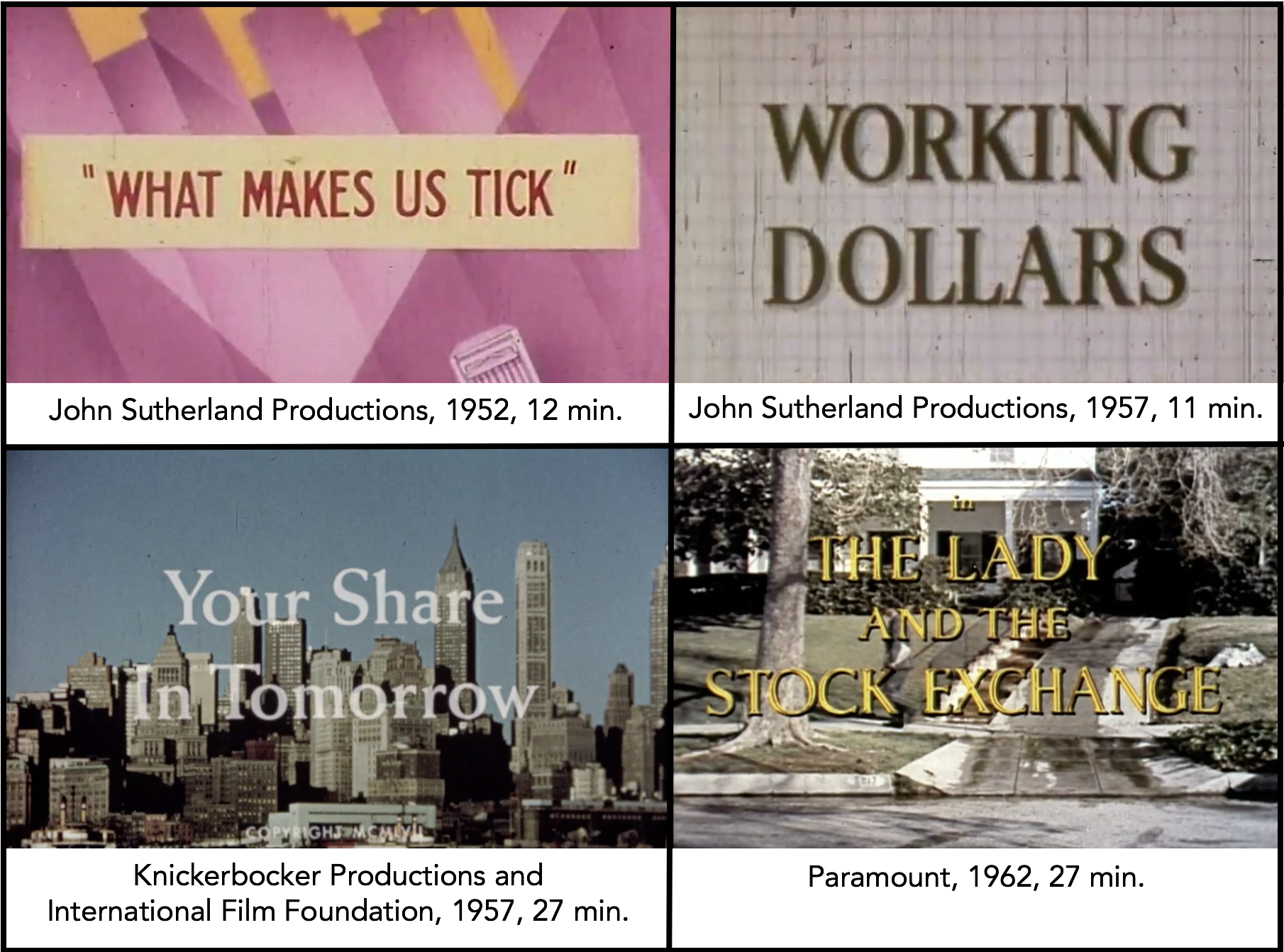

Used in concert with the Exchange’s Own Your Share (OYS) campaign (1954-1968), four films formed part of a foundational attempt to bring millions of individual, middle-class investors into the economic and ideological fold of the Exchange.[3] Using the narrow framework of personal finance to limit debates over participation in the economy, these films—seen by millions in theatrical and nontheatrical settings and on TV—joined an extensive Medienverbund of print advertisements, department store displays, radio sponsorship, talks, and television programs.[4] While we should think of them within a longer tradition of institutional advertising and PR, I’m interested in how their institutional utility rests on their teaching claims. Open didacticism not only obfuscated the Exchange’s vested interests, it elevated financial investment—a practice with outcomes decided by a fundamentally unknowable future—to the status of teachable, and therefore masterable, body of knowledge.

Because they claimed to teach something about how to participate in stock markets, NYSE films ran into the problem of risk and the future orientation of investment.[5] The most useful thing they could teach would be how to reliably profit—that is, information that doesn’t actually exist. While the Exchange used several strategies to manage this difficulty, here I focus on one: the films’ obsessive use of fact to overwhelm viewers with a sense that they’re mastering the important details of the Exchange’s operation—a sleight-of-hand that purports to teach one thing (how to invest successfully) while offering evidence of something else (process and logistics).

This dynamic is most visible in the execution of a stock order, a process treated in all OYS films. Moving step-by-step, the films take pains describing the precise movement of orders, people, and information through the complex architectures of the exchange. See, for example, What Makes Us Tick (8:25-10:15). Representing the Exchange as defined by connectivity, speed, and equal access to trading information, NYSE films fill their runtime with detail: explanations of specialized equipment (trading posts, annunciator board, quotation room, central ticker room, pneumatic tube), trading terms (round lot, odd lot, market order), and roles (specialist, analyst, broker, quotation clerk). Although edifying, this information is irrelevant to the process of making an informed decision as to whether and how to invest in the stock market.

Exemplifying the process film, this ‘how it’s made’ approach sidesteps difficult questions about risk. It fits with a standard sponsored film strategy of teaching seemingly neutral processes (e.g. farming or menstruation) as a pretense for broad ideological lessons.[6] Rather than focusing on the political, historical, economic, or future complexities of international finance, films lean on descriptions of the concrete and temporally circumscribed process of order execution as their primary explanatory framework.

NYSE films invoke—and constantly repeat—the transactional moment of the stock buy to memorialize the (implied: successful, long-term) union between investor and market. Exchange films avoid prognostication on an unwieldy and unknowable future by substituting a short material action with certain ends (a stock sold and bought) as the driving narrative action.

Although packed with such bits of fact, films like Tick mention, but always defer, explanation of the right information needed to succeed in the marketplace. Employing direct address to instruct viewers to engage with an off-screen authority, this deferral promotes brokers as educators and confidants, reinforces investment’s predictability, and attempts to spur viewers into action.

Not unlike the email wrapper for “Market Commentary,” the films’ positioning of brokers as gatekeepers to ‘the facts’ reinforces finance workers’ authority, professionalism, and expertise as curators of a parallel information economy. (As a corollary, of course, any omissions in the films can be overlooked, since that information ostensibly lies elsewhere.)

Ultimately, the educational frame of these films is the cornerstone of their intellectual and political project. With immense detail papering over self-interested silences, the films flatter viewers by initiating them into a world of specialized knowledge. First and foremost reassuring, they render complex and unpredictable processes simple while simultaneously positioning knowledge as the ticket to success. The trappings of educational address likewise serve a legitimizing function for the apparently disinterested and knowledgeable finance industry.

A partial and partisan lesson, the consequences of this strategy extend to far-reaching questions concerning the diverse pedagogies wielded by a range of institutions beyond formal schooling systems. How institutions attempt to manage citizens’ and consumers’ orientation to knowledge continues to be a crucially important question for the twenty-first century; the promulgation of self-serving epistemologies founded not on critical thinking but on appealing beliefs and entertaining logics holds ramifications for the organization of public and private life. As private institutions increasingly attempt to pass as public intellectuals and leaders—often at the expense of educators—it’s vital to examine institutions’ attempts to cultivate our relationship to information, argumentation, and knowledge itself. I’ll return to this task in the next installments of this column.

Image Credits:

- Screenshot from What Makes Us Tick. (author’s screen grab)

- This chart appears in every newsletter, explaining specialized terms and stating the legally mandated: “Past performance is no guarantee of future results.” (author’s screen grab)

- Screenshots of title cards from NYSE “Own Your Share” films. (author’s screen grab)

- Own Your Share: What Makes Us Tick video.

- See stock order process in The Lady and the Stock Exchange, 17:00-20:30.

- Screenshot referring readers to experts from the Market Commentary email newsletter. (author’s screen grab)

- Wise words from “Market Commentary,” 9/9/19 and 2/8/16, respectively. (author’s screen grabs)

- Miranda Joseph, ‘Gender, Entrepreneurial Subjectivity, and Pathologies of Personal Finance’, Social Politics 20, no. 2 (2013): 248; Mary Mellor, The Future of Money: From Financial Crisis to Public Resource (London: Pluto Press, 2010), 59. [↩]

- Randy Martin, Financialization of Daily Life (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002), 3. [↩]

- The Exchange targeted those making over $5,000 in 1955 ($48,000 today). [↩]

- Janice M. Traflet, A Nation of Small Shareholders: Marketing Wall Street after World War II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 2013), 62-64; Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Archives and Archaeologies: The Place of Non-Fiction Film in Contemporary Media’, in Films that Work, 22. [↩]

- Arjun Appadurai, ‘Afterword: The Dreamwork of Capitalism’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 35, no. 3 (2015): 483. [↩]

- J. Emmett Winn, ‘Documenting Racism in an Agricultural Extension Film’, Film & History 38, no. 1 (2008): 35, 40; Michelle H. Martin, ‘Periods, Parody, and Polyphony: Fifty Years of Menstrual Education through Fiction and Film’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 22, no. 1 (1997): 23. [↩]

Even negative events that happen in your life are learning opportunities. Humans learn from trial and error, which isn’t possible without some negative events to help to push us to be creative and innovative. Focus on the chance to grow and learn from each experience.