“The Most Wonderful Time of the Year”: Christmas Classics Old and New

Kathleen Loock / University of Flensburg

In Germany, Christmas is not Christmas unless one has watched Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel (Three Wishes for Cinderella), an East German/Czechoslovakian co-production from 1973 directed by Václav Vorlíček. Based on a variation of the familiar Grimm Brothers’ fairytale by Czech writer Božena Němcová, this movie delivers magic, memorable music (by Czech composer Karel Svoboda), and beautiful winter landscapes (filmed around Moritzburg Castle near Dresden) along with a surprisingly feminist female lead, who is not only smarter than the prince but also beats him at horse-riding and marksmanship. The popularity of Drei Haselnüsse remains unbroken. More than forty years after its first release, the movie has become an essential part of the German Christmas viewing ritual and a holiday staple in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Norway, and Switzerland as well. Drei Haselnüsse is comparable to It’s a Wonderful Life in the United States. Jonathan Munby describes Frank Capra’s 1946 Christmas classic as “a mythical text” that has assumed the status of “the Christmas movie, the Hollywood carol, the benchmark against which all other Christmas films are judged” (55, emphasis in original). If Munby argues that It’s a Wonderful Life provides “an ontological guarantee of Christmas itself” (56), the same is certainly true for Drei Haselnüsse in other parts of the world.

The enduring popularity of such movies raises questions about the ways in which popular culture shapes memories, experiences, and ideas of Christmas and about the desire to repeat and replay the same stories every year. Beyond the sense of comfort and reassurance that Christmas classics seem to provide, they also draw attention to a “deluge of new Christmas movies” (Rebecca Alter) that is not only cranked out by the usual suspects Lifetime and Hallmark during their seasonal programming of made-for-TV holiday romances but also by Netflix, which began to produce its own share of original Christmas fare in 2015. How do these new Christmas movies relate to the old classics? What are they offering viewers? And do they affect the cultural logic of Christmas as both a local and a global festival?

While the origins of Christmas can be traced back to Roman times, Christmas traditions as we know them (with tinseled trees, filled stockings, Christmas cards, and Santa Claus) only emerged in the mid-nineteenth century when the rambunctious, carnivalesque holiday was reimagined as a family-centered, domestic affair that took place in the home, no longer in the public sphere (cf. Miller, “A Theory” and “Christmas”; Nissenbaum; Sigler). Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843) fueled this “invention of tradition” (Eric Hobsbawm), which “claims links with an ancient past but is really an almost entirely new festival” (Miller, “Christmas” 13), through an emphasis on the carnival tradition of the temporary inversion of established (social) hierarchies and visitations from the dead (Mundy 164). Literary texts were important for the construction of modern Christmas, but as John Mundy has pointed out, the reinvention of the holiday “relied as much, if not more, on visual imagery” (164) ranging from illustrations in books and magazines, advertisements and Christmas cards to holiday movies: “[S]ince the end of the Second World War, Hollywood films have increasingly dominated big-screen representations of Christmas and ensured that movies, including their soundtracks, have become an integral aspect of our contemporary experience of the Christmas festivities, whether at the cinema or on television and DVD” (Mundy 165).

Over the past decades, the list of Christmas classics has kept growing with movies such as Miracle on 34th Street (Seaton, 1947; remade in 1994 by director Les Mayfield), Die Hard (McTiernan, 1988), Home Alone (Columbus, 1990), The Muppet Christmas Carol (Henson, 1992), or the improbable Bad Santa (Zwigoff, 2003). Christmas movies attain their status as classics through regular repetition, which encourages and sustains ritualized consumption practices. Television plays a crucial role in canonizing these films after their theatrical releases and in endowing them with a timeless, festive quality. In Germany, the Christmastime programming schedule for Drei Haselnüsse is published well in advance each year, creating excitement for the holiday and the prospect of ample opportunities to (re)watch the familiar movie on television. In addition, Drei Haselnüsse is also available on Netflix, along with the streaming service’s Christmas originals.

In recent years, Hollywood has grown reluctant to produce new Christmas movies due to “the constraints of release windows and limited marketing opportunities” (Snart). Netflix, the “catch-all disrupter” (Heritage), has occupied the niche with “a series of original films operating somewhere between the Hallmark channel and the multiplex in terms of production values” (Snart). Unlike Hallmark or Lifetime, however, Netflix produces Christmas movies for global audiences. A Christmas Prince (Zamm, 2017) and co. all contain essentially the same ingredients that made It’s a Wonderful Life or Drei Haselnüsse Christmas classics in their respective countries (from the carnivalesque de-stabilization or reversal of power structures, to miraculous interventions, and a festive winter atmosphere) without trying very hard to replace or compete with their precursors. If Christmas classics tend to have dark, serious, or sad undertones, Netflix’s original movies are their shallow, feel-good counterparts. They postulate postfeminist ideas of domesticity and family life, painting Christmas as a holiday which emphasizes “the continuity of home and tradition” (Miller, “Christmas” 437).

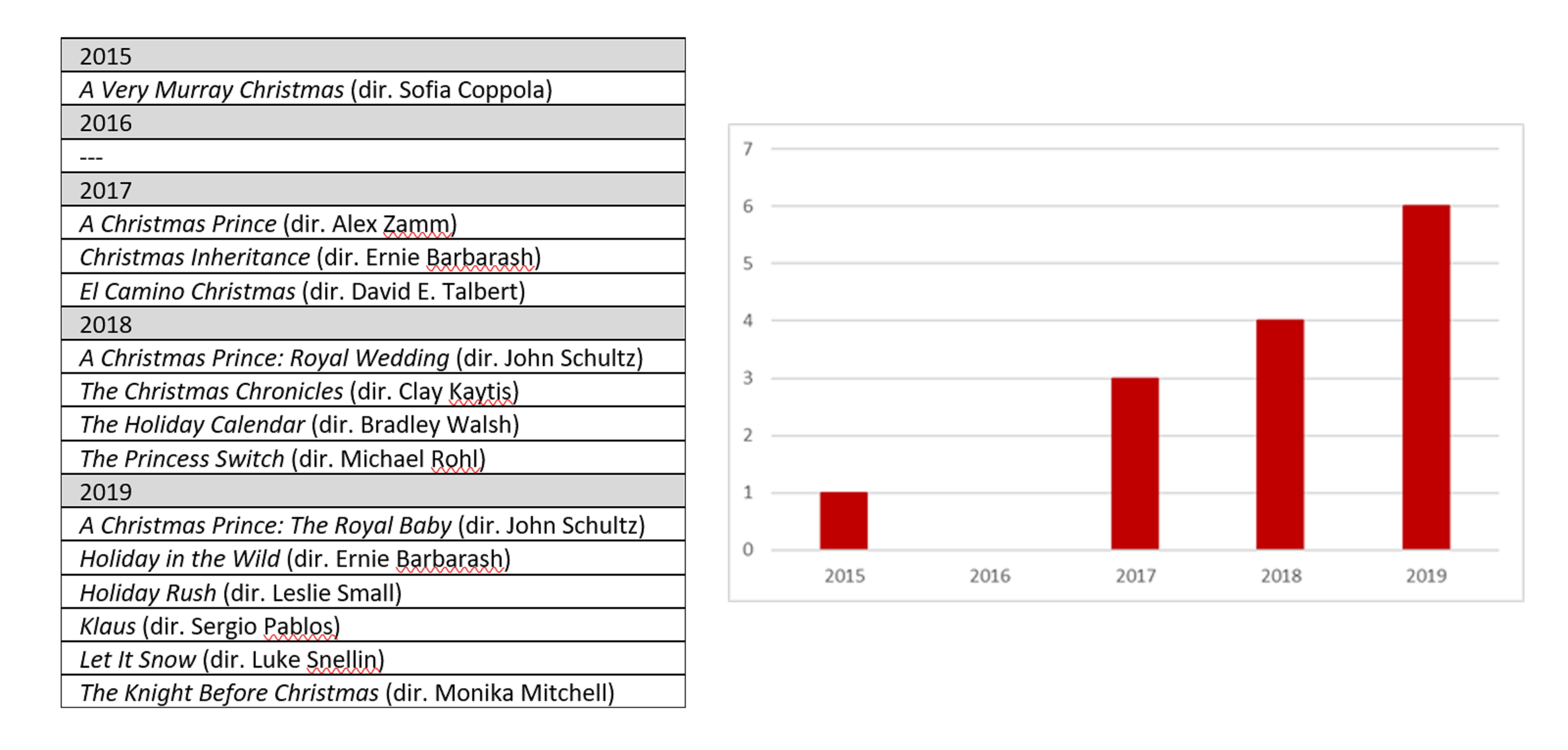

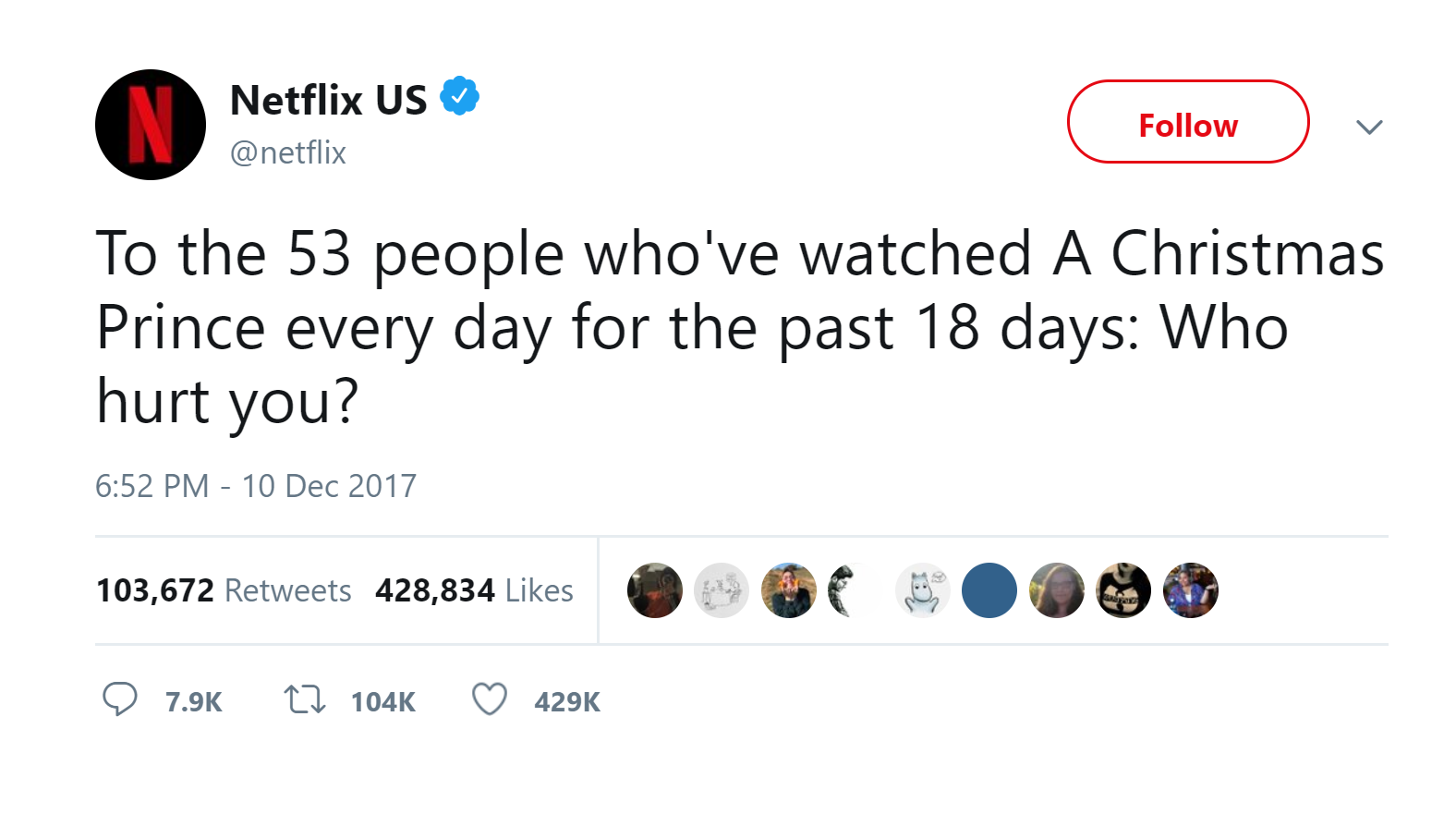

Netflix’s creepy tweet exposing repeat viewers of A Christmas Prince in 2017 seems to indicate that the streaming giant is not interested in the kind of repetition that would transform its originals into timeless Christmas classics. Instead, Netflix wants to create new, serialized content based on its most successful formulas, such as the annually released sequels A Christmas Prince: Royal Wedding (Schultz, 2018) and A Christmas Prince: The Royal Baby (Schultz, 2019). In times of “peak TV,” Netflix employs Christmas as an algorithmic keyword that promises a global viewership both familiarity and novelty. The “deluge of new Christmas movies” (Rebecca Alter), which was recently ridiculed on Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show, generates an upbeat, sugary, harmless Christmas spirit. These films are all about getting viewers into a cozy, seasonal mood, and they stand out among the season’s timeless classics, which, like Drei Haselnüsse and It’s a Wonderful Life, always also contain critical comments about class, gender, and how we live together.

Image Credits:

- Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel is a Christmas classic in Germany as well as in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Norway, and Switzerland.

- It’s a Wonderful Life and Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel are both considered to be definitive Christmas movies.

- Table and graph by author.

- The 2019 Christmastime programming schedule for Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel on German public television.

- Netflix’s Twitter account makes creepy comment about repeat viewers of A Christmas Prince.

- Stephen Colbert makes fun of the deluge of new Christmas movies on The Late Show.

Alter, Rebecca. “The Definitive Guide to 2019’s Deluge of New Christmas Movies.” Vulture 25 October 2019. Web. 29 October 2019. https://www.vulture.com/2019/10/81-christmas-movies-on-hallmark-lifetime-netflix-and-more.html

Heritage, Stuart. “Why Does netflix Keep Making So Many Cheap TV Movies?” The Guardian, 10 July 2019. Web. 29 October 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/jul/10/netflix-secret-obsession-tv-movies

Hobsbawm, Eric. “Introduction: Inventing Traditions.” The Invention of Tradition. Ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983. 1-14.

Miller, Daniel. “A Theory of Christmas. Unwrapping Christmas. Ed. Daniel Miller. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993. 3-37.

Miller, Daniel. “Christmas: An Anthropological Lens.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7.3 (2017): 409-442.

Munby, Jonathan. “A Hollywood Carol’s Wonderful Life.” Christmas at the Movies: Images of Christmas in American, British and European Cinema. Ed.Mark Connelly. London: I. B. Tauris, 2000. 39–58.

Mundy, John. “Christmas at the Movies: Frames of Mind.” Christmas, Ideology and Popular Culture. Ed. Sheila Whiteley. Edinburgh: EUP, 2008. 164-176.

Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Christmas. New York: Knopf, 1996.

Snart, Stephen. “The Christmas Chronicles Review: Kurt Russell’s Santa Can’t Save Netflix Turkey.” The Guardian, 21 November 2018. Web. 29 October 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/nov/21/the-christmas-chronicles-review-kurt-russells-santa-cantsave-netflix-turkey

Sigler, Carolyn. “‘I’ll Be Home for Christmas’: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films.” The Journal of American Culture 28.4 (December 2005): 345-356.

Television plays a crucial role in canonizing these films after their theatrical releases and in endowing them with a timeless, festive quality. Christmas is an algorithmic keyword that promises a global viewership both familiarity and novelty. Christmas is a great family festival.

Jill Newslady had a great time reading out all these titles I think.

This is the best and most quality article I have ever read.

Your article is flawlessly written! I’m deeply engaged and can’t wait to see your future updates.