#NotMyAriel: Safe Race-Swapping and the Casting of a Black Woman as Fish

Shearon Roberts / Xavier University of Louisiana

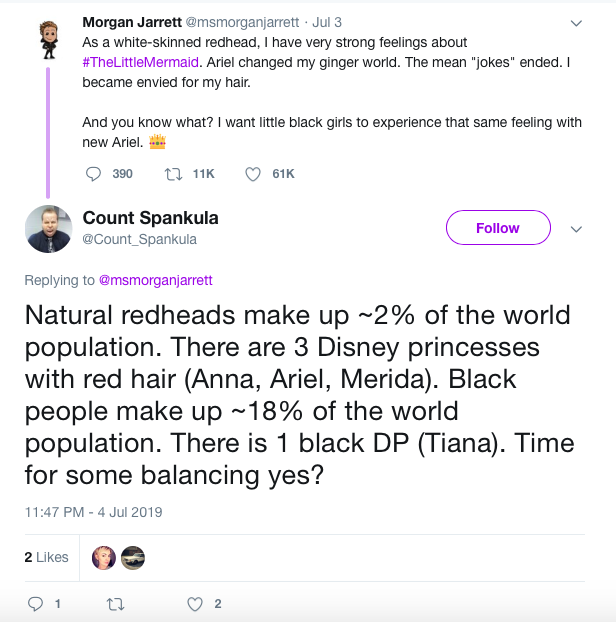

On the 10-year anniversary of The Princess and the Frog (Clements and Musker, 2009), Disney announced it will offer audiences a second Black princess. Like her predecessor Tiana, she will follow in similar fashion, and instead of being a frog, she will get a slight improvement, she will be a fish, who at least is half-human. The casting of Halle Bailey as the Little Mermaid lit up social media at the end of summer 2019. The hashtag #NotMyAriel trended at the same time as #Tiana, and a line can be connected between the two. Fans of the original 1989 animation claimed the race-swap casting was a loss for redhead representation. Some even resorted to Trumpism slogans demanding to “Make the Little Mermaid Great Again.” Fans of the race-swap argued that there have been three redheads among the princesses: Ariel, Merida, and Anna, despite redheads only accounting for less than two percent of the global population, and Black women, a far larger number.

Supporters of Disney’s race-swap argued that Tiana spent over 90-percent of the film as an animal, diminishing audiences the opportunity to be entertained fully by a Black princess. They demanded that it was time Black audiences got a second Black princess. Opponents pointed out that it should be open season on race-swapping and that Tiana, Mulan, and Pocahontas can now be acceptable race-swaps and cast by white actors in live-action remakes.

The social media back-and-forth descended into a mix of racism, discussions about reverse racism, and oppression Olympics,[1] but the larger argument missing from the race-swap of The Little Mermaid (Marshall) was that it was safe. In fact, it was the least controversial move Disney could make in its current era of remakes, reboots, sequels, and live-actions that comprise the company’s second revival era.

As 2019 showed, Disney’s global media dominance resulted in record setting economic success. The company bested its previous record in 2016 by earning its total box office revenue by mid-year 2019 with still at least two more potential billion-dollar films to go (Frozen II [Buck and Lee] and Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker [Abrams]). In fact, there is evidence in 2019 alone that “safe” race-swapping can bring diverse audiences to the theaters and result in billion dollar success. One glaring race-swap in 2019 was the casting of Genie in Aladdin (Ritchie) as Black (Will Smith). The iconic role was played by Robin Williams, but technically it was not a white man’s role, just a funny man’s role, and the Genie was blue. The race-swap of a racially neutral character meant that Genie could be Black in 2019, and audiences could accept this. Not only would Genie be Black, he would be from the region along the Silk Road, which included North Africa, through the Middle East, and onward to Asia. Therefore, there was nothing controversial about Genie’s race-swap, other than the CGI look of Smith’s blue and whether he could live up to Robin Williams-levels of comedic performance. At the end of the summer, Aladdin returned $1.046 billion at the box office and drew in the global audience Disney hoped it would earn by casting the largest diverse cast it has assembled.

Besting Aladdin in summer 2019 was The Lion King (Favreau) at $1.616 billion, which dethroned 2017’s Beauty and the Beast (Condon) to earn the top spot for Disney’s remakes. The Lion King also had a casting race-swap, although much quieter and expected, as after all, the film features a storyline and setting on the African continent. Where the 1994 original animation barely featured Black voices cast in the lead roles, save for James Earl Jones as Mufasa and Whoopie Goldberg as Shenzi the hyena, the 2019 photo-realistic remake had a predominantly Black voice cast led by Beyoncé and Donald Glover. This was also safe recasting for Disney, as today’s audiences would likely not accept the argument that films with Black (voice) leads would not become global sensations in a post-Black Panther era. Like Genie, the lions, hyenas, and baboon of The Lion King are not human. They are animals or magical beings, and since they are not human, they can be any race, or rather Disney can make a case for what race they should be.

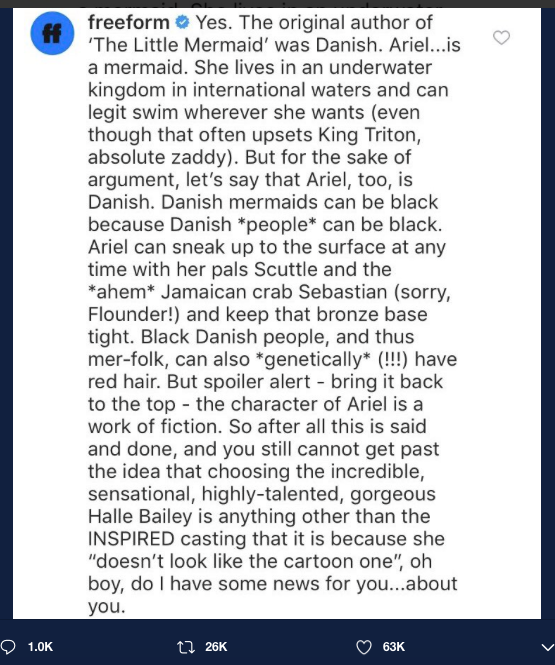

Therefore, Disney’s casting of Halle Bailey, a young, African American singer-songwriter-actress with dreadlocks as the Little Mermaid, is not revolutionary. She will be playing a fish. Although exhibiting human-like features, mermaids are ultimately an evolved form of amphibians, and as Ariel sings, she is an outsider who longs to be “part of that world.” While Disney itself did not weigh in on the controversy, one of its channels, Freeform, schooled critics on the casting choice in a Twitter post titled “An Open Letter to the Poor, Unfortunate Souls.”

The Freeform post argued that The Little Mermaid was originally a Danish tale, but that Ariel is set in international waters, and the crab Sebastian is Jamaican. The channel post notes that there are even Black Danes, and that they can also genetically have red hair. However, the most important argument of the Freeform post to audiences is that “the character of Ariel is a work of fiction.” In other words, there is a precedence set for race-swap casting. If a character can be classified as “fiction” or non-human, it passes a threshold for a tolerated race-swap in casting. Likewise, the race-swaps and gender-swaps happening across the Marvel Cinematic Universe also pass this threshold because super-heroes are technically unreal. Like Genie and mer-folk, superheroes are fiction, imagination, and cannot be referenced as real life individuals or traced to historical events. Therefore, the diverse castings of the MCU, like Zendaya Coleman as Mary Jane, or new diverse castings going forward, like Salma Hayek (Ajak) and Lauren Ridloff (Makkari) in The Eternals (Zhao, 2020), fit the test for safe race-swaps for Disney works. It is why few fans agreed with the counter-argument that Tiana, Mulan, or Pocahontas can also be race-swapped because their characters are “real,” as in, based on real, historical figures whose racial identities are known.

This rule-of-thumb allows Disney to hail its woke choices around diverse casting without truly offending traditional audiences. It draws more audiences of color to the theatres to see beloved diverse leads or to root for diverse leads while maintaining traditional Disney-Marvel-Lucasfilm, etc. fans. It has resulted in tentpole experiences and billion-dollar box office records. It allows Disney to sell both Black mermaid and redhead mermaid dolls at the same time. It keeps Disney’s stores, parks, digital streaming services, films, merchandize and series consumed by the widest cross-section of audiences, including all groups and alienating few. What it does not do is move the needle on who audiences consider as cinematic leads. To date, outside of T’Challa and Simba, there is no Black prince or king anywhere among Disney’s studios. Likewise, there has yet to be a major Disney work with a Black woman lead who is elevated to equal status afforded white princesses. In fact, scholars acknowledge that fans of the Disney princess franchise have rated Tiana, Mulan, and Pocahontas as the least desirable and likable princesses.[2] Although Disney has provided diverse princesses their own films, their treatment in these works have rendered them second-class. Or in the case of Moana, in exchange for empowerment, they are not the interest of any man’s affections nor do they seek affection. In order to be a strong woman of color, they must eschew love, at least in Disney works.

Diversifying casting through race-swaps can arguably become token nods to calls for inclusivity in an industry that historically relegated Black and minority actors to sidekicks. However, the choices made to date can be classified as safe and in some cases problematic. The casting of Black women leads with white or non-Black male leads continues an erasure of the Black male as a leading man,[3] and perpetuates the desirability of a white male gaze on “othered” women.[4] This occurred in A Wrinkle In Time (DuVernay, 2018), which erased racial difference to the point that all major male-female relationships were racially diverse. On one end, this casting can be considered progressive, imagining a world where love and affection is color-blind. At the same time, Meg Murry (Storm Reid) only accepts her curly hair after Calvin O’Keefe (Levi Miller), her white co-star, insists to her that he likes her natural hair, reminding audiences that the fictional world Meg inhabits still connects to Black women’s real world insecurities around their natural hair and white acceptance of their beauty as the only legitimate kind.

On the other hand, in Black Panther, Okoye snatches her own wig as liberation, and as a strong general, still loves, as she can both lead war and have a relationship with W’Kabi. However, Black Panther stands alone because in creating a fully fleshed out Black nation and civilization, it includes the widest spectrum of Black experiences on screen.[5] This is something that a token, safe attempt at race-swap in a film whose world is shaped by existing hegemonies will struggle to do. And while Wakanda is also fiction, it demonstrates a model for how far films must still go to truly offer more expansive representations of Blackness on screen to wider audiences. In the meantime, offering diverse audiences a Black mermaid is giving them one chair at a table while Disney cashes in from the meal. It leaves diverse viewers at least full for now but wishing the meal had more salt.

Image Credits:

- Halle Bailey announced to be Ariel in Disney’s live-action adaptation of The Little Mermaid.

- Fans conduct a diversity check on redhead representation in Disney princess films.

- Fans debated whether non-white Disney princesses can be cast as white in remakes.

- Freeform Twitter Post: “An Open Letter to the Poor, Unfortunate Souls,” July 6, 2019.

- Martinez, Elizabeth. “Beyond Black/White: The Racisms of our Times.” Social Justice 20, no. 1/2 (1993): 22–34. [↩]

- See Dundes, Lauren, and Madeline Streiff. “Reel Royal Diversity? The Glass Ceiling in Disney’s Mulan and Princess and the Frog.” Societies 6, no. 4 (2016): 35. [↩]

- Jackson, Ronald L. Scripting the Black Masculine Body: Identity, Discourse, and Racial Politics in Popular Media. New York: SUNY Press, 2006. [↩]

- Kaplan, E. Ann. Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film and the Imperial Gaze. New York: Routledge, 2012. [↩]

- Bowles, Terri P. “Diasporadical: In Ryan Coogler’s “Black Panther,” Family Secrets, Cultural Alienation and Black Love.” Markets, Globalization & Development Review 3, no. 2 (2018); Toldson, Ivory A. “In Search of Wakanda: Lifting the Cloak of White Objectivity to Reveal a Powerful Black Nation Hidden in Plain Sight (Editor’s Commentary).” The Journal of Negro Education 87, no. 1 (2018): 1-3. [↩]

Pingback: Monday Night Links! | Gerry Canavan

It’s always difficult to write a resume yourself, especially if you don’t understand anything about it. But experts will definitely help you. Forward here

I have thought so many times of entering the blogging world as I love reading them. I think I finally have the courage to give it a try. Thank you so much for all of the ideas!

I “have some news” for you, Professor Roberts. I’m still waiting for a bio pic about MLK with the “incredible, sensational, highly-talented, gorgeous” Taylor Swift in the lead role.

There’s just one major problem with this argument, you use the logic that they’re fictional characters whose race is not central to the plot, and thus it doesn’t matter who plays them. But this has never been ok in movies, as a character’s appearance will always matter, not just with race and gender, but their height, weight, hair texture, hair color, eye color, voice, and any other physical trait. Do you think people would be any happier if say, Bella Ramsey played Ariel despite the fact she’s white, or if Viola Davis played Tiana? When it comes to established characters, the actor needs to look like said character, colorblind casting only works on original characters whose race isn’t important.

And it isn’t just race or gender swapping that people complain about. Any massive change to a character’s appearance will receive backlash. For example, the original design for Sonic in the movie received massive hate from the whole internet, eventually forcing Sony to go back and change it to match his iconic appearance. If a character’s appearance doesn’t matter if it isn’t essential to the plot, then why did the trailer receive hate if Sonic’s appearance isn’t any more important to the plot than Ariel’s, apart from being a fast hedgehog? They’re just iconic characters who are known for their appearances, and if you change a character’s appearance, people are gonna get mad. This also happened when Chris Pratt didn’t have Mario’s iconic Italian accent when voicing Mario in the movie, and again when he didn’t have Garfield’s grumpy voice in the trailers for the Garfield movie. People even were particular enough to get mad about the SIZE OF MARIO’S ASS, that there was even a petition. Star Wars fans also always complain when characters from animated shows like Ahsoka, Cad Bane, and the Grand Inquisitor don’t look exactly like they do in the shows when appearing in live-action.

If people just don’t like changes to characters in general, why do you think Race and Gender Swapping are any more acceptable than any other change, and why do you expect people to accept these changes anymore? It also doesn’t make sense to call these people racist or sexist just for hating character change in general, especially when plenty of POC and Women complain about these changes as White Men do. The solution for representation is simple, CREATE NEW CHARACTERS, original characters with their own backstories and struggles representing these people, instead of recycling a story not made for them. Keep existing characters regardless of who they are true to their source material as much as possible, don’t change their race, skin color, sex, orientation, height, weight, hair texture, hair color, eye color, or character design to what they originally were. Smaller lesser known characters can often get away with changes I mentioned, but any iconic characters can’t be changed at all.