In Toon with the Times: Diversity in American Commercial Animation

Mihaela Mihailova / University of Michigan

In December 2016, The Hollywood Reporter published a roundtable on the topic of “avoiding ethnic stereotypes and how to ‘break the mold’ of princesses” in the animation industry featuring seven White men. The backlash was instantaneous, addressing the inherent absurdity of inviting this particular group of “top toon creators” to reflect on questions of diversity and highlighting the glaring omission of obvious candidates such as Jennifer Yuh Nelson, who directed Kung Fu Panda 2 (2011) and co-directed its sequel, or Gina Shay, who produced Trolls (2016). While this animation “manel” is part of a larger problem, it is directly indicative of systemic issues in the American animation industry, wherein women make up only 20% of animation creatives, despite comprising 60% of animation students.

While demographic data on animation labor equality remains undeniably grim, questions of diversity and inclusion in animated productions — often conspicuously absent from broader cultural discourse on media representation — are worth a closer look. Firstly, because even though contemporary commercial animation often features more diverse casts than live-action films, this tends to fly under the radar of most critics. And secondly, because common misconceptions about the medium — from outdated notions of its target audiences to a narrow understanding of the scope of its content — often preclude a serious consideration of animation’s potential as a platform for inclusivity.[1]

Even animation critics are not immune to this tendency to marginalize the artform by overstating the implications of its otherness. Take, for instance, this response to the aforementioned roundtable debacle, which describes diversity in animation as a “tough concept to nail down.” According to the author, animated films are a “different matter altogether” because their “marked separation from reality” ensures that “any traits of diversity are capable of going unnoticed unless they either made explicit [sic] or designed that way to begin with.”

Let us put aside the fact that animation’s relationship to reality is the subject of an entire disciplinary subfield, animated documentary studies[2]; the use of medium specificity in an attempt to render one of the most pervasive media forms of our time immune to pressing social justice concerns begs the question — is diversity in animation really such a complicated matter? Or can toons — in all their colorful, kinetic, sometimes anthropomorphic glory — reflect the experiences of underrepresented groups and celebrate marginalized identities just as meaningfully as live action?

A little Bertie told me that they can. Lisa Hanawalt’s Tuca & Bertie (2019), an adult-oriented Netflix show that centers on the friendship between a toucan and a song thrush, has recently made waves for being a rare breed — a female-centric, woman-led show in an animated TV landscape dominated by men. Voiced by stars of color (Ali Wong, Tiffany Haddish, and Steven Yeun), and celebrated as an “ode to female friendship, healing, and survival,” Tuca & Bertie has simultaneously modelled animation’s potential to feature diverse acting talent and its capacity to tackle topics commonly sidelined in mainstream productions, or else rarely presented from a feminist perspective (as sexual harassment and trauma are, in this case). While this particular show is addressed to grown-up viewers, a number of recent kid-friendly animated programs have contributed enormously to gender and LGBTQ representation in children’s media, highlighting the ways in which animation’s broad reach can bring inclusivity and diversity to the forefront of youth culture. Noelle Stevenson’s She-Ra and the Princesses of Power (Netflix, 2018-present), which features a predominantly female cast, offers a family-oriented take on female empowerment and sisterhood, while also depicting the loving relationship of a main character’s two dads. Steven Universe (Cartoon Network, 2013-present) has been praised for continuously dismantling gender norms, celebrating non-binary identities and queer icons of color, and depicting the first same-sex wedding in a mainstream children’s show. Finally, Amazon’s kids-oriented Danger & Eggs (2015-17), broke ground as a queer-inclusive cartoon co-created by Shadi Petosky, the only openly trans showrunner in American animation. The series, which features several queer characters voiced by LGBTQ talent, culminates in a season finale set at a Pride celebration, during which a young girl (voiced by trans rights activist Jazz Jennings) sings a song about her first day attending school “as her authentic self,” marking a milestone for trans inclusivity in animated TV.

While these shows are all produced by streaming giants such as Netflix and Amazon or TV channels such as Cartoon Network, in the past decade, online crowdfunding platforms have enabled independent animation creators — women and people of color in particular — to directly respond to fans’ desire for a greater variety of diverse content in the medium. In 2013, Natasha Allegri’s Kickstarter campaign for Bee and PuppyCat (2013-present), her manga-influenced show about a young woman and her magical four-legged companion, raised almost $900,000, demonstrating the need for adult-oriented animation which “puts [women], their experiences, and their tastes first.” More recently, Hair Love (2019), an animated short about a Black father learning to do his daughter’s hair, attracted nearly $300,000 on Kickstarter, exceeding its original funding target fourfold. Despite being conceived as a festival short, the film has since been picked up for distribution for Sony Animation, playing in theaters ahead of The Angry Birds Movie 2 (Van Orman, 2019). Creator Matthew A. Cherry has explicitly linked the overwhelmingly positive response to his project to the importance of representation, specifically the film’s positive portrayal of Black fatherhood.

Despite this recent push for more inclusive content, animation is not immune to many of the issues that have plagued commercial American media’s approaches to diversity and representation, including queerbaiting, tokenism, and other half-hearted, superficial gestures towards representation. The recent fan outcry against botched LGBTQ representation attempts in Netflix’s Voltron: Legendary Defender (2016-18) productively illustrates the intensity and breadth of impact (both positive and negative) that a TV-Y7 cartoon can have on marginalized audiences of all ages. During a much-publicized San Diego Comic Con panel ahead of the show’s seventh season, showrunners Joaquim Dos Santos and Lauren Montgomery revealed that Takashi “Shiro” Shirogane, one of the show’s central characters, is gay, and teased a storyline involving his former partner, Adam. This news was greeted with an outpouring of fan enthusiasm, which quickly turned to accusations of queerbaiting and references to the “bury your gays” trope as soon as the season aired, never exploring their relationship and revealing that Adam had died while Shiro was away. To make matters worse, in an attempt to smooth things over through what has been aptly described as an instance of “epilogue representation,” the series finale’s post-script features a tacked-on wedding between Shiro and an extremely minor male character. This insensitive, perfunctory approach to queer representation ultimately sparked important discussions of authenticity and pandering, becoming a warning to creators to “stop preemptively outing their characters” in a manipulative attempt to generate positive buzz.

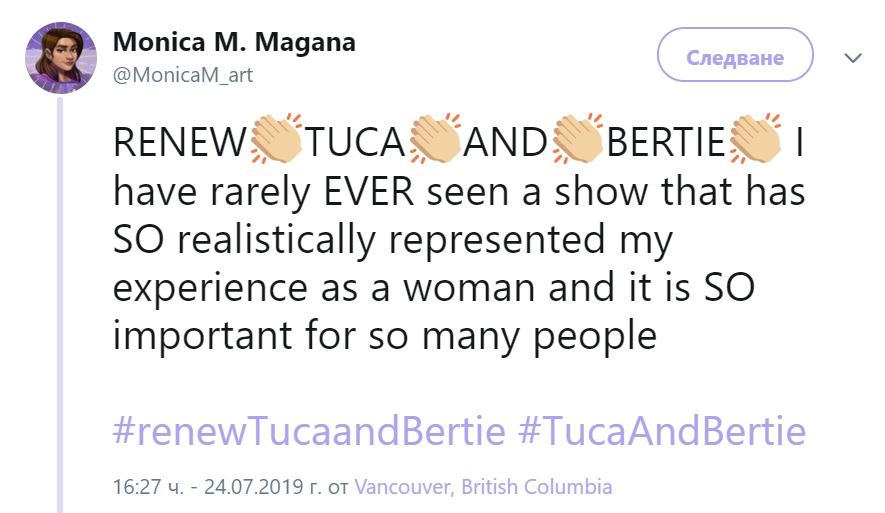

Whether drawn or filmed, representation matters — and its absence can be keenly felt. After Netflix unexpectedly (and inexplicably) cancelled Tuca & Bertie after its first season, fans of Hanawalt’s cartoon quickly took to twitter to express their dismay and outrage on behalf of a show that focuses — with a notable degree of honesty and compassion — on women’s experiences in a way that remains rare to see on the small screen. In particular, tweets by women, such as the one pictured below,

commonly noted the dearth of female-oriented content available to them, while highlighting the show’s importance from the perspective of representation. At the same time, Tuca & Bertie’s cancellation brought renewed attention to a larger Netflix trend of prematurely “axing shows led by people of color and women,” serving as a sobering reminder that, in the broader context of diversity in contemporary TV, one bird show does not a summer make. Still, as even a relatively cursory overview of feminist, queer-inclusive, and race-conscious animated content can demonstrate, diversity in animation is not a tough concept to nail down. Women, people of color, and queer creators have been nailing it.

Image Credits:

- New series bringing diversity to animation. (Bee and PuppyCat image from Polygon; Steven Universe from The New York Times; She-Ra and the Princesses of Power from Decider; Tuca & Bertie from Deadline)

- Netflix’s Tuca & Bertie, an animated example of marginalized experiences and identities finding screen space.

- Amazon’s Danger & Eggs‘s Pride Parade Finale.

- The Kickstarter-funded Hair Love (2019) exponentially exceeded its funding goal.

- An example of the strong social media outrage at Tuca & Bertie‘s cancellation.

Excelente publicación. Está muy completa y correcta, aparte es maravillosa y interesante.

Deseo que en el futuro hayan más series televisivas que sean abiertamente inclusivas.

Estos últimos años he notado en los dibujos animados que incluyen ahora más personajes no binarios y chocas de pelo corto. La diversidad debe enseñarse a los niños como algo que es incriticable y que es bueno ser cómo quieres ser.

A propósito, ví She-Ra, y debo decir que tiene una historia muy buena. La relación de los personajes es tan natural y inclusiva.

Excelente post. É muito completo e correto, além de maravilhoso e interessante.

Espero que, no futuro, haja mais séries de televisão que sejam abertamente inclusivas.

Nos últimos anos, notei nos desenhos animados que agora eles incluem mais personagens não binários e colisões de cabelos curtos. A diversidade deve ser ensinada às crianças como algo que não é crítico e que e que é bom ser como você quer ser.

A propósito, eu vi She-Ra, e devo dizer que ela tem uma história muito boa. A relação dos personagens é tão natural e inclusiva.