Postmodern Pastoralisms:

Artists Reveal the Invisible Infrastructures of “The Cloud”

Maria Skouras / University of Texas at Austin

Since the emergence of mechanization, technology has been framed in opposition to nature as well as inextricably linked to it. Now that technology is commonplace in our everyday lives, the natural world is frequently employed as a metaphor to symbolize complex processes and market new products and services to consumers by applying familiar, illustrative, and benign terms. This practice influences how technology is perceived, ignores threatening power dynamics, dismisses the significance of social and political factors in shaping technology, and further alienates users from critically thinking about issues surrounding the Internet and data. With much at stake due to technological ignorance, more proficient understanding of these topics is an imperative to maintain access to information, privacy, and security. In pursuit of demystifying these topics, artists are working to reveal the physical infrastructures and networks that support the Internet and help debunk their long-held association with natural occurrences.

Dating back to the 19th century, American authors like Henry David Thoreau and Herman Melville portrayed industrialization as an aggressive or disruptive force bound to estrange citizens from a simpler, more peaceful existence. This negative narrative began to shift as powerful individuals touted the advantages of using machines to complete mundane manufacturing tasks and facilitate national development during the Industrial Revolution. American politicians celebrated the positive changes mechanization and factories were destined to bring for society, turning technology into an abstract metaphor for progress. [1]

Machines were praised as being able to do the hard, time consuming work that would in turn free individuals to pursue more spiritual ambitions that would bring them closer to nature. [2] Otherworldly abilities were cast upon technology and it was imbued with mysterious God-like powers. Both fascinating and bewildering, the magic of technology came to embody national aspirations towards reaching the highest echelons of innovation and achieving greatness. Culture and technology professor Leo Marx used the term “technological sublime” to explain the state of transcendence that technology was seen capable of while combining the best parts of the rural (purity) and urban (knowledge) divide. [3]

Today, the language we use to describe fundamental aspects of the Internet perpetuates the connection between technology and the natural world and seeks to obscure its complex, and oftentimes problematic, inner workings. For instance, the infrastructure that stores high volumes of user data on the Internet and makes it accessible on any device from remote locations is widely referred to as “the cloud.” This term was first employed as a way to describe a network of nodes and the unknown networks they were linked to forming an amorphous, cloud-like shape.

The use of cloud services for personal and corporate purposes are numerous, but to illustrate just a handful, if you store photographs on Amazon Prime, have an email account with Microsoft Office 365, work on projects with colleagues using Google Docs and Dropbox, watch streaming services like Hulu or Netflix, ask Siri or Alexa to answer questions, post on Facebook, update your resume on LinkedIn, or Skype with friends near and far, then you are using cloud technology. Even though the number of global internet users and companies that utilize cloud-based services is growing, as of 2014 the majority of Americans did not know what the cloud is or how it works or even that they were already using it themselves. Further, many believed that bad weather impacts cloud computing. With the ubiquity of cloud-based services in 2019, it is likely that more internet users are at least aware of the cloud even though the name obfuscates its physicality and deters a base understanding of how it functions.

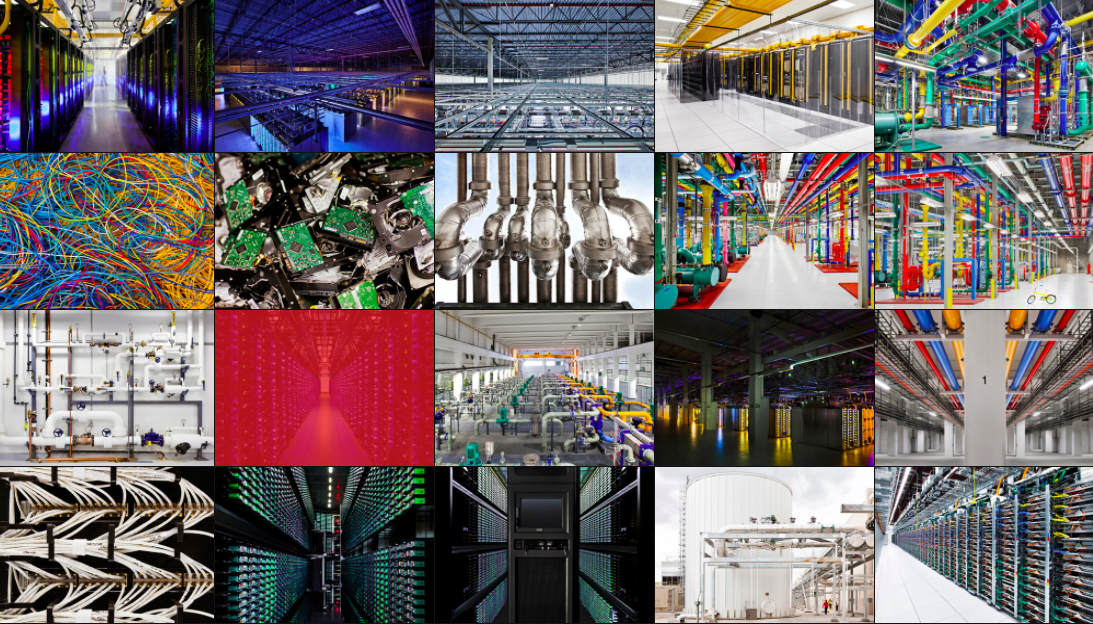

“The cloud” conjures images of puffy white clouds floating across a serene blue sky, while the reality is that cloud-based data is stored on a multitude of servers in warehouse-like data centers. The location of data centers is most often out of sight in remote areas. Media scholars Jennifer Holt and Patrick Vonderau elaborate on the contradiction of the indispensability of data centers to digital media infrastructures and their invisibility, which obscures their role in processing and storing information [4]. Beyond that, this invisibility cloaks security concerns over the protection of personal data and the environmental impact of data centers, which has serious implications for energy consumption and climate change.

Unsurprisingly, companies like Google and Apple might open their doors to the public once a year for a closer look at the inside of a data center yet sparingly share details on the mechanics of it. More widely accessible, Google’s Data Centers website features video tours and photographs of these restricted spaces “where the Internet lives.” The “Inside a Google data center” video is of a location in South Carolina and features wide angle shots of the center surrounded by a green landscape and river with clouds passing overhead. It is reminiscent of the hopeful spirit of the Industrial Revolution that machines were assured to bring humans closer to nature.

The bright primary colors of the Google employee workstations and bikes outside contrast with the monotonous rows of silver servers lining the warehouse. Google employees introduce themselves and are shown bringing their pets to work and taking breaks to play foosball, putting a human face to the impersonal machinery. Strategically produced, the video provides a curated glimpse into the data center. As argued by Holt and Vonderau, the hypervisibility of some aspects of the data centers is as intentional of a choice as the invisibility of others. [5].

The secrecy surrounding the cloud has inspired artists to create works that expose aspects of how it operates or at least allow viewers to have a closer look at these essential yet hidden media infrastructures. As reported by Vice, artist and filmmaker Matt Parker teamed up with cinematographers Michael James Lewis and Sebastien Dehesdin to create a video series called The People’s Cloud. Together they traveled to critical data centers in Europe and interviewed engineers, marketing experts, economists, and other integral employees while touring the facilities and capturing footage of the semiconductors, fiber optic cables, magnetic storage units, and numerous other internal aspects of these technical systems. Combining investigative journalism with creative expression, they developed 5 short documentaries, additional videos, audio works, and installations that uncover the material, social, and abstract layers of cloud infrastructures. Each video is accompanied by a detailed essay, all of which can be accessed for free online.

What is the Cloud vs. What Existed Before?

Taking a different approach after his request to access and photograph Google’s data center in Oklahoma was denied in 2014, artist John Gerrard utilized a helicopter to capture aerial images for his photography series titled Farm. His images were then used to create a 360-degree animation and projection of the site to expose the infrastructure behind the internet. He saw the photographs as a continuation of his project Grow Finish Unit, in which he photographed industrialized pork production sites in rural locations. In linking the two projects he said, “Oddly it is visually similar to the architecture of the Google data farm. It is sort of like a postmodern pastoral.”

from John Gerrard’s website — photographed by Blake Gowriluk

Artist and geographer Trevor Paglen is also known for photographing data centers, particularly those related to the U.S. intelligence agency. Drawing attention to the tension between idyllic locations and the presence of stark data centers used for clandestine activities, he highlights these powerful yet oft-overlooked structures. He explains his work by saying, “My intention is to expand the visual vocabulary we use to ‘see’ the U.S. intelligence community. Although the organizing logic of our nation’s surveillance apparatus is invisibility and secrecy, its operations occupy the physical world. Digital surveillance programs require concrete data centers; intelligence agencies are based in real buildings; surveillance systems ultimately consist of technologies, people, and the vast network of material resources that supports them.”

Although the remote, rural locations of data centers have financial, environmental, and security motivations, they further shroud the centers in mystery and suggest a new iteration of the technological sublime which inhibits users from contemplating and understanding the systems they regularly use. The creative, investigative work of artists is essential to grounding the cloud and encouraging individuals to question and critique physical infrastructures and the sociotechnical systems that create and sustain them.

Image Credits:

1. Screenshot of artistic images of infrastructure from Google’s data center website

2. A painting titled “The Lakawanna Valley” by George Inness (1856) showing technology coexisting with or intruding upon nature

3. “Inside a Google data center” from Google’s G Suite YouTube Channel

4. The People’s Cloud Episode One from Matt Parker’s Vimeo page

5. Image of Google’s Data Farm at Pryor Creek Oklahoma

6. Photograph of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) by Trevor Paglen

Please feel free to comment.

- Smith, M.R. (1994) Technological Determinism in American Culture. In M. R. Smith & L. Marx (Eds.) Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism (pp.1-36.) Cambridge: MIT Press. [↩]

- Marx, L. (2000) The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. (35th Anniv) (p.169.) New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- Marx, p.195. [↩]

- Holt, J., & Vonderau, P. (2015). “Where the Internet Lives”: Data Centers as Cloud Infrastructure. In Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructure (pp. 71–93). University of Illinois Press. [↩]

- Holt & Vonderau, p.81. [↩]

Thanks for sharing.I found a lot of interesting information https://notepad.software/ here. A really good post, very thankful and hopeful that you will write many more posts like this one.