¡Viva el monstruo! – The Gill-man as a Symbol of Latinx Resistance

Casey Walker / University of Texas at Austin

At the March 2019 Senate confirmation hearings for David Bernhardt, President Trump’s pick to serve as interior secretary, protestors in the audience donned masks of the Gill-man from the 1954 film Creature from the Black Lagoon. Referring to themselves as “swamp creatures,” the protestors were there to draw attention to Bernhardt’s reputation as a member of the Washington D.C. oil and gas establishment and the very embodiment of the “swamp” that President Trump vowed to drain. Setting aside for a moment that a swamp is very different from a lagoon, this is not the first time the Gill-man has been read as a symbol of either sociopolitical anxiety or establishment resistance. Scholar Lois Banner notes that during the 1950s, these types of movie monsters were symbolic of fears of Communism, nuclear war, and/or the African American civil rights movement. [1] Filmed and released during the year-and-a-half-long road to the Supreme Court for Brown v. Board of Education, the case which legally ended racial segregation in schools, scholars often read the Gill-man in Creature from the Black Lagoon as a racialized Other.

But with respect to the Latin American roots of the story and also the South American setting of the film, can we also look at the Gill-man specifically as a symbol of the Latinx Other? The story of the film was originally conceived at a gathering at the home of Orson Welles in 1940, during the development of Citizen Kane. In attendance at the meeting were legendary Mexican actress Dolores del Río and soon-to-be legendary Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, along with William Alland, a member of Welles’ Mercury Theater. Alland later recalled that at this meeting, Figueroa “went on and on and on” about a “creature that lives up in the Amazon who is half-man and half-fish,” according to Latin American legend. More than a decade later, Alland was working as both a producer and story contributor at Universal-International Pictures and pitched the story idea to studio executives, calling it “The Sea Monster.” In a three-page memo he wrote to pitch the story, Alland instead gave credit for the story to “a South American movie director [sic].” [2] Whether this was just a faulty memory or an intentional concealment of Figueroa’s identity is unknown, but even to this day, published material usually gives credit to this unnamed director from South America or to Welles himself for hosting the party where the story was told.

Alland’s memo was turned into a treatment by Maurice Zimm and was expanded and re-written through multiple drafts of screenplays by writers Harry Essex and Arthur A. Ross. During these revisions, Alland and the writers expressed a desire to make the creature as human as possible and to create him as a symbol of “the natural.” Writer Ross later elaborated, “The more you attack what is natural in the world, the more likely it will do something to protect itself.” [3] The authors’ creation of a human-like creature with human desires, in addition to grounding the creature’s agency in its natural impulse to protect itself, pivoted the concept of the film’s titular character from “a sea monster” to a creature of nature attempting to protect its habitat from scientists appropriating its ancestors’ remains. Later, the creature becomes infatuated with scientist Kay Lawrence (Julie Adams), although it treats her more like a desired possession than a romantic equal.

These attempts to model the creature after a human’s shape, mannerisms, and desires inspired a sympathetic reading of the Gill-man. Filmed several months after the release of Creature from the Black Lagoon, Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955) most famously depicted these sympathies for the creature, when Marilyn Monroe’s character proclaims, “He wasn’t all bad. I think he just needed a little affection—a sense of being loved and needed and wanted.” Lois Banner explores the connection between the civil rights movement at the time (specifically the Brown v. Board of Education ruling) and Monroe’s defense of the Creature, concluding “it may have indicated a positive attitude toward racial difference.” [4] Reading the Gill-man as an indication of “a positive attitude toward racial difference” rather than just as a “sea monster” is partly how the perception of the creature changed over time from a symbol of sociopolitical fear to one of resistance against racial discrimination.

In addition to the Brown v. Board of Education decision, 1954 was an important and defining year in the history of civil rights struggles, especially with respect to Latinx citizens and immigrants. A few years earlier, The Migrant Labor Agreement of 1951 extended the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, part of the Bracero Program, which brought over 350,000 Mexican workers to the U.S. each year. This continual influx of Mexican workers, along with the growing anxieties over how to document them, led to the Immigration and Naturalization Service implementing the despicably titled Operation Wetback in 1954, an initiative designed to repatriate Mexican workers. Almost four million people of Mexican descent were deported in a four-year time frame. In the same year as the implementation of Operation Wetback, the landmark Supreme Court case Hernandez v. The State of Texas resulted in a unanimous decision which held that Hispanic Americans are equally protected under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, setting the precedent for future legal action on behalf of their struggle for equality. [5]

These huge events were ongoing upon the release of Creature from the Black Lagoon in 1954, a film that positioned the creature as a South American native whose tale was rooted in a Latin American legend as told by Mexican cinematographer, Gabriel Figeuroa. There is a Latinx foundation and essence to this film that cannot be ignored. The film also contains the representation of a primary Latinx character, that of Dr. Carl Maia, played by Spanish-born Antonio Moreno. Moreno was frequently cast as the “Latin Lover” character in numerous U.S. silent films, but his role in this film as a head scientist avoided conventional Latinx stereotypes of the time. The characters of Dr. Maia and that of the more stereotypical Captain Lucas (played by Portuguese descendent, Nestor Paiva) made up half of the expedition survivors at the end of the film and displayed agency, albeit limited, in the film. And while the designer of the iconic Creature costume, Milicent Patrick, was of Italian descent, she spent much of her childhood following her father around his construction projects in South America, becoming accustomed to the culture, traditions, and people of the continent where the film would be set. [6] This exposure was likely an influence on her concept and design of the Creature’s iconic look.

One person who likely never lost sight of Creature from the Black Lagoon‘s Latin American heritage was Guillermo Del Toro. The Mexican filmmaker worked on different iterations of scripts for a planned remake of the film, but Universal Studios turned him down. Undeterred, he created an original story based around a Gill-man who falls in love with a janitor (who also falls for him) at a high security government facility, which became the Oscar-winning film, The Shape of Water. The film focuses heavily on societal Others, such as a mute woman janitor, her black female co-worker, and a lonely, gay advertising artist, all of whom combine their efforts to rescue the Gill-man from the monstrous Colonel Richard Strickland before he can vivisect the creature for research. While the film has no obvious Latinx Other on-screen, Del Toro maintains the Latin American origin of the Gill-man in the story, positioning him as a potential Latinx Other, although not exclusively. By ultimately killing the character of Strickland in the climactic scene, the Gill-man serves as a symbolic and triumphant resistance to the misogyny, racism, and xenophobia that Strickland represents. In the current political climate, where Latinx families are separated at the U.S.-Mexican border and their children are placed in cages, we need these filmic Latinx symbols of resistance now more than ever. Frank McConnell writes that “each era chooses the monster it deserves and projects.” [7] For the Gill-man and the Latinx resistance it embodies, maybe that time is now.

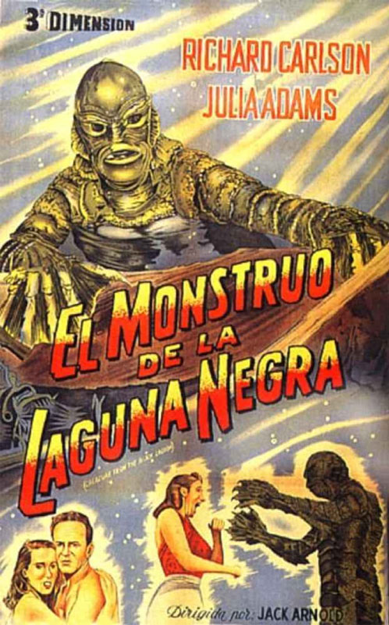

Image Credits:

1. “Swamp Creatures” Protest at 2019 Senate Confirmation Hearings

2. Mexican Movie Poster for Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954)

3. A Touching Scene from The Shape of Water (2017)

- Banner, Lois W. “The Creature from the Black Lagoon: Marilyn Monroe and Whiteness.” Cinema Journal (2008): 5. [↩]

- Weaver, Tom & David Schecter & Steve Kronenberg. The Creature Chronicles: Exploring the Black Lagoon Trilogy. McFarland, 2014, 13. [↩]

- Ibid, 13-34. [↩]

- Banner, 5-7. [↩]

- “Latino Americans: Timeline of Important Dates.” PBS. Accessed May 24, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/latino-americans/en/timeline/. [↩]

- Fate, Vincent Di. “The Fantastic Mystery of Milicent Patrick.” Tor.com. March 25, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2019. https://www.tor.com/2011/10/27/the-fantastic-mystery-of-milicent-patrick/. [↩]

- McConnell, Frank D. “Song of Innocence: The Creature from the Black Lagoon.” Journal of Popular Film 2, no. 1 (1973): 17. [↩]

This is absolutely disgusting. As a hispanic person, I’m very offended by your use of the term “latinx”. I don’t need some english-speaking know-it-all to say what I should be called.