Toward a Critical Theory of Scooters

Andy Fischer Wright / University of Texas at Austin

It is almost ludicrous at this point to not believe that new technology companies have widened societal inequalities. Whether this is through searching logics resulting in “technological redlining” [1] or a simple lack of access via the digital divide, there is much to problematize in the world of tech. However, one corner of technology that has been slightly under-recognized (with some exceptions) is ride sharing. Within this sharing economy exists an object of culture that hit the streets relatively recently: dockless scooters. It is my aim to develop the bones of a critical theory for the scooter as it exists in culture.

To first make myself perfectly clear, I do not want to spend a thousand words and three minutes of your time raining abuse on what some could consider an irreplaceable and life-changing form of transportation. Scooters and similar dockless rideshare technology can potentially act as tools to help people get to places in cities that grow too quickly in complex gentrifying processes, or act as a temporary solution for the classed icon of car ownership, or even be a valuable tool of mobility for those who are otherwise physically unable. My intention is not to criticize the users, but to explore the different features of these devices with a critical eye.

According to the circuit of culture [2], there are five interrelated aspects of a cultural object: production, consumption, regulation, identity, and representation. The production of scooters is, like all consumer electronics, highly problematic. If we look at the trends of scooter development, the three key priorities that companies reiterate in a standard press release are rider safety, hardware durability, and longer charge time. Though these are all ostensibly positive advancements, popular press tends to focus on safety without analyzing how the trend of simply releasing new scooters is highly problematic from an environmental perspective. Even without the popular social media trend of visibly destroying scooters, the model of continually replacing hardware instead of maintaining it comes with the corollary cost of an unending labor cycle for those mining rare metals, manufacturing the components, and assembling the final product. [3]

Moving toward consumption, I turn to the question brought up in a recent paper [4] problematizing technology more generally: “One must ask how emancipatory a technology is, how much autonomy it induces when, for example, it overwhelmingly remains the preserve of those who are already most free.” This is indeed the model for scooters; ‘Ridesharing 2.0’ is a philosophy that is targeted specifically at cities whose citizens need a solution for a transportation problem that is already a matter of privilege. According to a recent press release, market leader Bird is marketed as “last-mile electric vehicle sharing company” whose intended clientele are “looking to take a short journey across town or down that ‘last mile’ from the subway or bus.” This is not a device intended for commuting, but to fill a certain sub-niche within a niche.

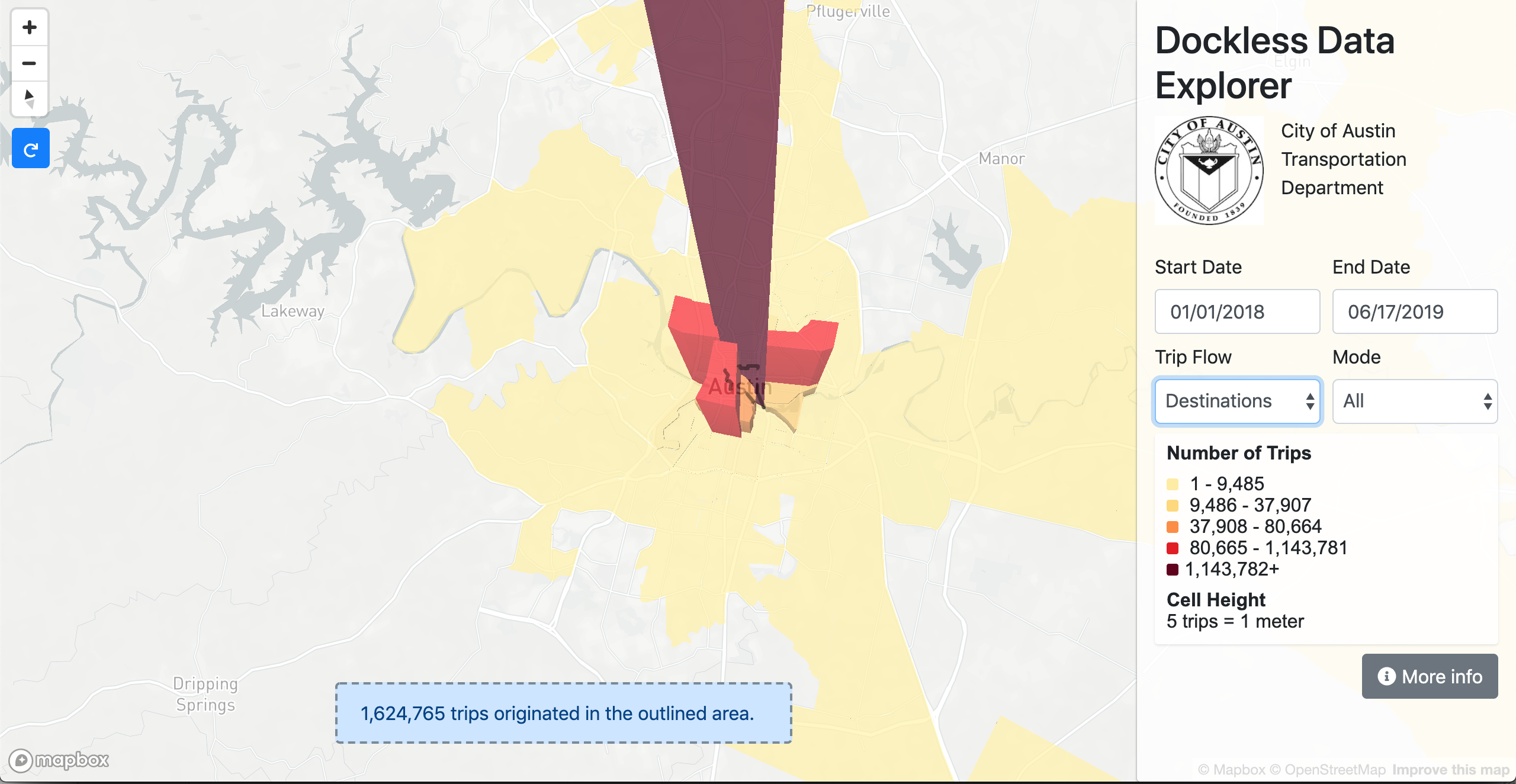

And even if the battery lasted long enough for people who have been pushed out of city centers by gentrification to take a scooter to their old neighborhoods, the task of actually locating a device to ride is daunting. According to data collected by the City of Austin, of the 1.6 million dockless vehicle trips that began in the center of downtown Austin, over 1.1 million concluded within that same small region; it seems that scooters are intended to be within the city, for the city. And while Bird operates on three continents, the overwhelming majority of their partner cities are large cities within North America, most of which contain large universities. Though this could be interpreted as a result of the most prominent scooter companies being based in North America and less than three years old, it can also indicate that the intended consuming audience is in fact intended to be individuals living downtown in populous North American cities. All logics of a scooter’s affordability are negated by a lack of access to any except those already within the city.

Regulation of scooters is theoretically easy but practically much more difficult. For instance, the University of Texas at Austin has a series of guidelines for scooters based on the findings of a work group in December 2018. Geofencing makes the maximum speed of any scooter on campus eight miles per hour, a heavy fine for improper parking reinforces the importance of designated scooter parking zones, and there was a University-wide email claiming faculty and staff would soon be prohibited from riding commercial scooters for “work-related purposes.” Outside of UT, a scooter was famously used as a tool of regulation in locating a young Austin bank robber who made good his escape on a scooter.

However, the physical scooter proves in need of less regulation without a branded network. Without the software and connection to a corporate entity, a scooter would not be slowed down on entering campus. If the rider shared the scooter with a known community instead of trusting another anonymous app user to pick up the scooter next, they might be less likely to abandon the scooter in the middle of the sidewalk. And without the tie to the rider’s digital double, scooters might even be used by university staff to quickly get across campus without worrying about leaving a paper trail tied to their credit card and cell phone. Most regulation seems to not address scooters themselves but the issues that arise from their role in the corporatized ridesharing system.

While the scooter has a representation in and of itself, we cannot separate it from the connected identities of those who interact with it every day. Though customers have undoubtedly grown to be more than just those riding the final mile home from the subway stop, another identity that has sprung up more recently are those connected to scooters via their power outlets. Facing high demand and a comically ridiculous logistics issue of charging tens of thousands of batteries every night, large scooter companies now use ‘juicers’ to charge scooters in down times and deliver them to key points across the city. As independent contractors, juicers are shipped chargers by scooter companies and paid according to pickup location, charge level, and a timely drop off in a convenient hub. The containment of scooters within downtown areas is further reinforced by monetary incentives for dropping scooters closer to downtown.

If this is Ridesharing 2.0, then juicers are the second iteration of drivers in an even more ruthless system. Due to the nature of their compensation, to earn a living, juicers must collect scooters in large quantities, driving rented trailers and pick up trucks to places their app tells them will yield better profits. And yet, the juicer and the rider never interact with one another. This separation of rider and juicer is highly troubling; to a scooter rider, the juicer is an even more invisible part of the process than even the most silent driver. There is a grim phantasmagoria of Uber’s autonomous fleet in Ridesharing 2.0, reminding us that inequalities continue to persist and are ignored by futurists.

And so, we come to a conclusion that dockless scooters, while potentially an affordable, ‘ecofriendly’ solution to local travel, are in execution highly problematic. Yet for all of this we cannot simply erase scooters off the face of the planet any easier than we can eradicate petrochemical dependency (though, admittedly, this would be great.) Perhaps a more practical solution is to address the structural issues Ridesharing 2.0 takes advantage of, including a lack of affordable and equitable public transportation. By providing more communal and safer options for traveling in and around cities, we can solve the issue that created scooters.

Image Credits:

1. An image of a scooter, the focus of this piece.

2. Anonymized dockless rideshare data from the City of Austin. Higher bars and darker colors indicate rides that originate in the small downtown area stay within the downtown area. Supplemental data not included here indicate that under 10 total rides either originate or end within surrounding suburbs, such as Pflugerville or Round Rock.

3. A garage full of charging Bird scooters. Image taken from a tutorial for more efficient charging.

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism.

New York, NY: New York University Press. [↩] - Du Gay, P., et al. (2013). Doing Cultural Studies: The story of the Sony Walkman. Vol. 2. London: SAGE. [↩]

- The author was unable to find any evidence specifically pointing to unethical labor practices by the companies that produce the scooters. However, he can say colloquially that the global electronics trade is known for horrific and inhumane labor practices. [↩]

- Keyes, O. Hoy, J., and Drouhard, M. (2019). “HumanComputer insurrection: Notes on an anarchist HCI.” In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Proceedings (CHI 2019), May 4–9, 2019, Glasgow, Scotland, UK. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300569. [↩]