Grace and Frankie Open the Door: Dramedy, Netflix, and Small Screen Lily Tomlin

Kelly Kessler / DePaul University

When Grace and Frankie launched as an original Netflix comedy series in 2015, the Internet was all a twitter in anticipation of Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, feminist icons of 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, reuniting a full 35 years after their blockbuster feminist manifesto 9 to 5. Despite the fact that anything with Fonda and Tomlin had me at “hello” and the duo’s interactions and roles as simultaneous foils and unexpected soul mates were what made the show so special, I want to take this opportunity to consider Tomlin and her contested space in the televisual landscape. Although Tomlin has visited and at times frequented the small screen ever since her 1966 debut on The Garry Moore Show, something about 21st century generic innovation and allowances of the Netflix era opened up a space for Tomlin, one just out of reach for the comedienne for much of the last half-century.

It’s not as if series television had wholesale shuttered its electronic doors to comediennes or ladies of standup comedy. Wanda at Large and All-American Girl may have floundered, but Roseanne’s ratings blew everyone out of the water and Grace Under Fire and Ellen scored five seasons each. But those women were more traditional stand-ups or joke-tellers. Tomlin’s bread-and-butter was one-woman sketch comedy, trotting out her cadre of eccentrics. A 1976 New York Times article defines her style as “docu‐comedy” and “sentire” or “sentiment/feelings cum satire.” Its author Ellen Cohn repeatedly questions the small screen marketability of Tomlin’s performance style and evokes its tendency to render television producers and executives gun-shy and baffled. She says “Docu‐comedy? Sentire? Poetry? On Friday night in prime time? It’s enough to make the toughest network vice president hang his head and weep.”

This discomfort on the part of television execs didn’t keep Tomlin from away from the small screen. She was a series regular on Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In from 1969 to 1973 and had won five primetime Emmys by 1981, including those for her 1973 and 1975 specials, Lily and The Lily Tomlin Special, and her 1981 all-star Vegas-themed reflection on art versus commerce Lily: Sold Out. She later won a daytime Emmy for the animated The Magic School Bus, clocked-in 46 episodes of Murphy Brown and 34 of The West Wing, and appeared in a string of other series including the ABC dramedy Desperate Housewives, the FX thriller Damages, and HBO’s Eastbound and Down.

Rather than embracing the comedy style which had unnerved TV execs, however, her post-Laugh-In gigs tended to illustrate her breadth and knack for skillfully doing something else. Her stage act and comedy albums had not only included the well-known Edith Ann and Earnestine, but a parade of characters from Susie Sorority, radio evangelist Sister Boogie Woman, and lounge singer Bobbi-Jeanine to disaffected punk-rock adolescent Agnes Angst, struggling feminist Lynn, and prostitutes Brandy and Tina. Often such characters’ parallel existences helped construct Tomlin’s larger humorous and heartfelt projection of struggling humanity. In 1976 Cohn had described Tomlin’s characters by saying, “They are meant to touch us and tickle us; they are meant to set us thinking. Thigh‐slapping is not prohibited neither is it slavishly sought. Tomlin is satisfied with the smile and sigh of recognition.”

Although Polydor who distributed the bulk of Tomlin’s 1970s albums may have been at this ease with such a sigh of recognition, her act lacked the kind of climactic and comedic button standard to most situation comedies of the 20th century. Although Grace Under Fire and Roseanne cultivated a combo of emotion, pathos, and slapstick, they also followed a pretty traditional sitcom structure raising, complicating, and solving a problem with some kind of humorous action and moving on to the next episode with only marginal memory or seriality. Not until the early 2000s and 2010s was serialized dramedy commonplace on American TV, exemplified by HBO’s lady-driven variety with Sex and the City, Weeds, and The Big C. Whereas critics hail these shifts for allowing space for the “comic genius” of a Louis CK or Larry David, these evolutions in genre, continued splintering of viewers, and the rise in offbeat original streaming series also helped open a space for a comedienne who had frustrated broadcast strategies for decades.

The embrace of shows like Grace and Frankie opened a door just the shape of Tomlin’s comedic introspection. The show takes two big characters—Fonda’s acerbic society matron and makeup mogul and Tomlin’s aging bohemian artist—and provides room—not unlike Tomlin’s Tony winning The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe (hereafter Search for Signs)—to feature a mix of humorous foibles and pain. Although perhaps more dram-EDY than DRAM-edy, the show doesn’t always demand the laugh, but does allow Tomlin moments of excess whether chanting “blood on my hands” while smeared in faux monkey blood protesting the use of palm oil in her yam-based vaginal lube or practicing guttural Tuvan throat singing. Alongside such big bits and big laughs, the show explores the pain of later-in-life divorce, as the frenemies are thrust together after their husbands reveal they’ve been having a 20-year affair. Like Tomlin’s feminist divorcee Lynn in Search for Signs, they now have to strike out on their own and discover power outside of their men as they buck cultural notions of aging womanhood (all the while sharing the screen with cast-off actresses “of a certain age” like Marsha Mason, Estelle Parsons, Mary Kay Place, and Swoozie Kurtz).

The very characteristics that made the show Tomlin-friendly irked reviewers. The Hollywood Reporter insisted Grace and Frankie felt more like a network show than “something trying to stand out in the streaming world” while Vulture criticized the show, produced by Friends’ Marta Kauffman, for being too much like a traditional sitcom via its “bigness of the physical comedy,” embrace “of set-’em-up, knock-’em-down jokes,” and what the reviewer saw as a “seeming aversion to authentic human pain.” A Daily Dot reviewer faulted Netflix’s agreement to allow Kauffman to conceive the show as a series and not just pilot, claiming the producer’s sense of security acted as “fertilizer for misplaced grandiosity.” I argue these flaws cultivate a Tomlin-esque sweet spot, one embraced by her 1985 Search for Signs which was described by the New York Times as treating the audience to “an idiosyncratic, rude, blood-stained comedy about American democracy and its discontents.” As season one opens with Sol and Robert announcing their affair and plans to leave their wives, the show’s focused exploration of Grace and Frankie’s desperation alongside bigger comedic moments allows it to blend with other Netflix genre hybrids like the more drama-leaning Orange is the New Black (a show that notably provided a space for 50-something butch lesbian comic Lea DeLaria) and Tomlin’s tendency toward “sentire”.

Alongside these shifts in genre, a splintering television landscape and viewership has led to the kind of niche marketing which has provided an “out” for the type of anxiety 1970s execs may have felt regarding Tomlin’s docu-comedy style. No one is expecting a 25 rating or 20 million viewers anymore. Add in the branding and economic model of Netflix, which has allowed offbeat, niche television(ish) series to thrive one full season at a time, dropping all episodes on the same day, and the scene was set. Season 2 of Grace and Frankie ranked 19th out of the 22 original Netflix series with only 757 thousand viewers (versus Fuller House’s 7.3 million). Despite ratings, a reported audience resistance to ads depicting the politically polarizing Fonda, and the fact that the show stars two women in their late seventies and early eighties and traffics in talk of vaginal dryness, Alzheimer’s, broken hips, arthritis, and ageism, the series—low ratings and all—is heading into its sixth season and sits as Netflix’s longest-running comedy series with Tomlin already garnering four Emmy nominations and unplanned audiences perhaps finding it unexpectedly relevant. As Fonda said in a 2015 NPR interview “It’s like making one very long movie, and because it’s Netflix you don’t have to have a button on the end of every episode, you know, to keep people coming back next week. You can just kind of make it all flow together.” This distribution/viewing structure also allows the show to emerge as a kind of extended set more akin to Tomlin’s one-woman shows and LPs, weaving together experiences, developing the “sentire,” and allowing the comedy and drama to build upon each other. It may have taken nearly half a century since her Garry Moore debut, but television seems to have caught up with the genius of Tomlin.

Image Credits:

1. Billboard on Vine Street in Hollywood for Season 3 of Grace and Frankie

2. Clip from Tomlin’s 1975 Album Modern Scream

3. Strip of television shows on which Tomlin appeared (various sources)

4. Clip from Lily: Sold Out (CBS, 1981)

5. Clip of Agnes Angst from The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe with commentary by Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner (original source unknown)

6. Season 2 trailer of Grace and Frankie (Netflix)

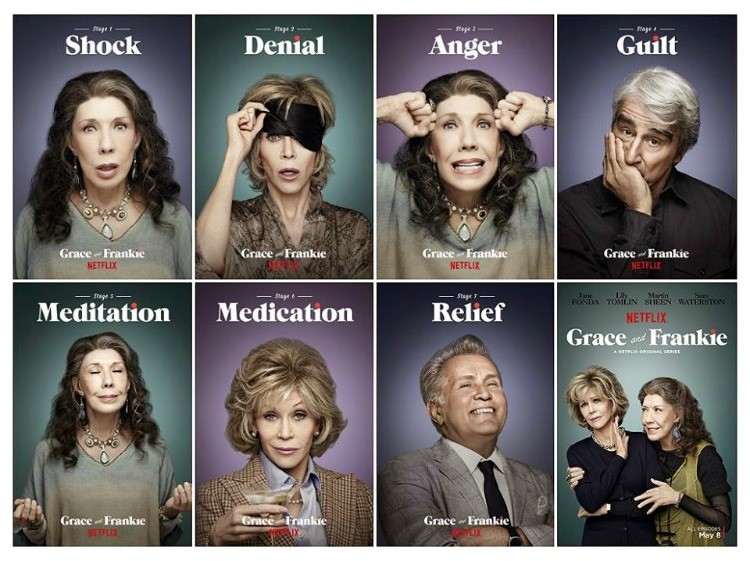

7. Season 1 “stages of grief” advertising campaign (Netflix)

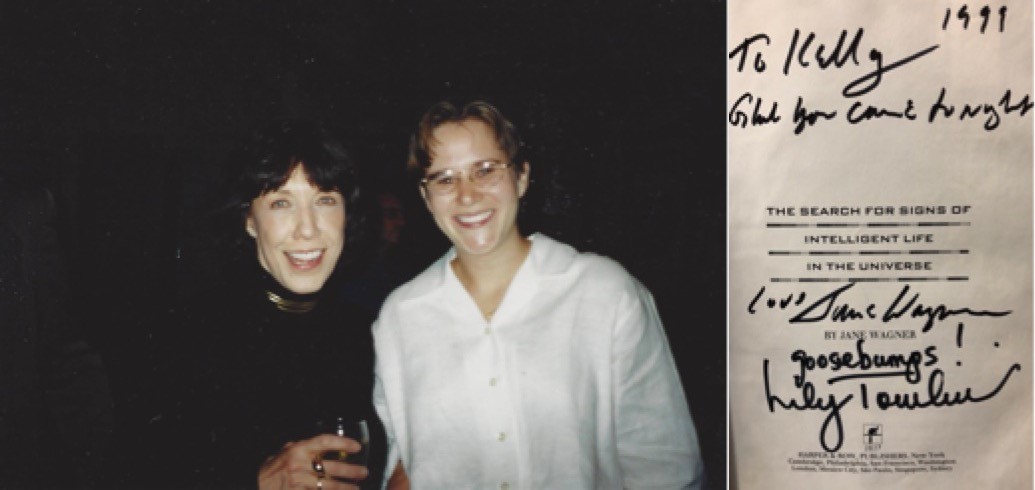

8. The author with Lily Tomlin and autographs from Tomlin and Wagner (circa 1999, author’s collection)

Please feel free to comment.