There are Black People in the Future: Digital Technology and Black Prescience

Sarah Florini / Arizona State University

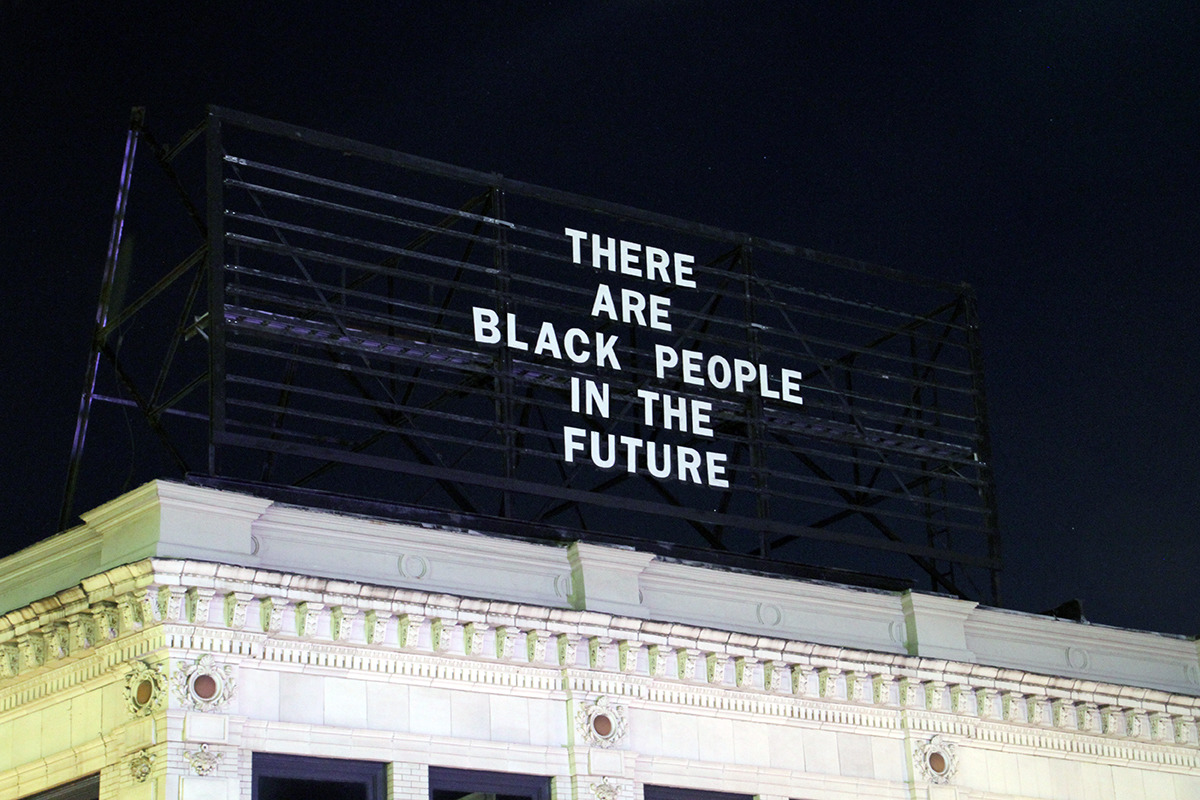

In spring 2018, artist Alisha Wormsley erected a billboard in Philadelphia reading, “THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.” Originally a playful jab at speculative fiction, which tends to imagine a future that is overwhelming white, the phrase has come to be an Afrofuturist mantra, representing not only the presence of Black people in the future but their role in shaping it. As I have participated in Black digital networks over the last decade, this phrase has become my shorthand for a consistent cycle. Practices that emerge from and develop in Black networks often become de rigueur internet culture a few years later. Here I outline three moments that revealed how networks of Black users – their practices and challenges – are often always already in the future.

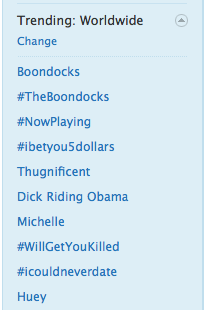

The network that has since come to be known as “Black Twitter” pioneered networked co-viewing, i.e., live tweeting television. In the early days of Twitter, Black users created a more homophilic network and used the platform in a more conversational manner. Black users created reciprocal networks and engaged in discussion, verbal games and humor, and eventually began watching television together. As early as the 2009 BET Awards, Black users were using Twitter to create a networked watch-party. The following year, Black Twitter created so much traffic that the Trending Topics, Twitter’s algorithmically produced list of most tweeted about phrases or hashtags, was dominated by names and phrases from the award show. Black Twitter users could be found on Sunday nights watching The Boondocks, but not before sending out the call to participate. “Time for the Boondocks” would regularly appear in the U.S. trending topics, and by the end of the 2010 season 3, the Trending Topics were dominated with Boondocks related phrases every Sunday night. After which, it seemed as if everyone turned the channel simultaneously to MSNBC for To Catch A Predator and was cracking jokes about Chris Hanson and iced tea pitchers. Before many even knew what Twitter was, Black users had established the practice of live tweeting as a strategy for a collective viewing experience.

Similarly, independent Black podcasters were at least two years ahead of the current podcast boom. Between 2012 and 2014, Black podcasts flourished. By the time Serial, the podcast that is credited with kicking of the resurgence of podcasts, debuted in October 2014, Black podcasters were already well ahead of the trend. As podcasts began to proliferate in 2015, independent Black podcasters had already established a robust presence, anticipating both the value and the popularity of the medium.

Most recently, Facebook, which also owns Instagram and WhatsApp, announced that its future development will focus more on facilitating smaller and more closed social interactions. While the plans announced will have relatively small ramifications for current user practices, the discourse used represents a marked shift from Facebook’s original stated purpose of “making the world more open and connected.” Mark Zuckerberg wrote of the change saying:

Over the last 15 years, Facebook and Instagram have helped people connect with friends, communities, and interests in the digital equivalent of a town square. But people increasingly also want to connect privately in the digital equivalent of the living room. As I think about the future of the internet, I believe a privacy-focused communications platform will become even more important than today’s open platforms.

He goes on to outline the rationale for this assertion, and for the future trajectory of the company, by pointing to users’ desire to gain greater control of their audience (which Zuckerberg equates with “privacy”) and for more ephemerality, preventing older posts from coming back to haunt users later.

Siva Vaidhyanatha has argued that this move is likely motivated by Facebook’s desire to solidify its dominance in the same manner as WeChat, a mobile phone app so popular in China that it is embedded into almost every aspect of life. The changes Zuckerberg describes would do much to undermine Facebook’s competitors and shape Facebook in WeChat’s image. However, Zuckerberg’s rhetoric of moving from digital “town square” to “digital living room” reaffirms a conceptual shift that began in Black digital networks several years prior.

Beginning in 2015 and through the run up to the 2016 presidential election, Black users began making increased use of formal and informal barriers that insulated their interactions from outsiders. Black users, especially Black women, have long been the targets of harassment and abuse online, and this vitriol intensified and coalesced into a coordinated political effort in 2014, continuing to do so through the 2016 election. Both Imani Gandy and Terrell Starr wrote pieces in 2014 detailing years of harassment and abuse that women, particularly Black women, endured online and Twitter’s steadfast unwillingness to curb the hostility. That same year, attacks became more coordinated and sustained. Users from message boards like 4Chan began creating fake accounts in attempts to impersonate, infiltrate, and “sow discord” among those they termed “SJWs,” social justice warriors. As the 2016 election approached, anti-SJW internet trolls, white supremacists (who had rebranded themselves the “alt-right”), and misogynist movements like GamerGate and the Men’s Rights Movement had well-worn strategies for making public and semi-public social media platforms nearly unusable for marginalized people. Added to this were the over-zealous Bernie Sanders supporters, who exacerbated the historic tensions between class and race in leftist movements, and the Russian bots and sock puppet accounts who imitated and amplified each of these existing social conflicts. Black users, who were a primary target, were forced to carve out spaces where they could interact without such hostilities.

Now, this kind of abuse has increasingly become the norm. Though Zuckerberg (unsurprisingly) never directly mentions the problem of harassment and abuse, the desires he attributes to users – controlling one’s audience and the permanence of posts – are intertwined with strategies users employ to avoid the hostility that can result from public or semi-public internet sharing. This discursive shift from Facebook, a platform used by 68% of Americans, signals that mainstream discussion of social media now presupposes a desire among the broader population for more sequestered digital spaces.

Yet again, Black users have anticipated digital trends, engaging in and developing practices that are becoming the norm. So often, academics only value Black knowledge and perspectives for understanding race and racism. But, when you critically and earnestly engage Black people and Black thought, your understanding of our digital landscape increases exponentially. There are Black people in the future, and they have beaten us there.

Image Credits:

1. Alisha Wormsley

2. Twitter Trending Topics (author’s screen grab)

3. Mark Zuckerberg

4. Amnesty International’s Toxic Twitter Campaign

Please feel free to comment.

Big, Thank you for some other magnificent post. Digital technology is great. The place else could anybody get that type of info in such an ideal method of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m on the search for such information.

Mobile is not just our future it is completely related to our business and life. Mobile device are our communication tool for worldwide their popularity are increasing. Great post on mobile technology.