Lucifer’s Women and Doctor Dracula: Conjuring a Cult-Cult Canon, Pt. 2

Phil Oppenheim / Oppanopticom / EPIX / Brown Sugar SVOD

“Cult” is a confrontational sensibility and set of aesthetics that “seeks to promote an alternative vision of cinematic ‘art’, aggressively attacking the established canon of ‘quality’ cinema and questioning the legitimacy of reigning aesthete discourses on movie art” [1]; cultist consumption marks “a radical refusal to become associated with the anonymous mainstream.” [2] Or maybe cult media appreciation amounts to only “minor subversions and assertions of individuality” that leave its viewers “feeling better about ourselves and our world … [a] simultaneously dangerous and safe trip” that results in a “pleasurable transgression” [3]; on the other hand, perhaps being a cultist is more profound, and can “save your life,” instituting a form of “therapy, self-medication, means of private escape and pragmatic material for furnishing a meaningful existence.” [4] For some, its lauded oppositionalism is really just a “species of bourgeois aesthetics, not a challenge to it,” [5] a “conflict within (rather than against) the bourgeoisie” that serves to “reaffirm rather than challenge bourgeois taste and masculine dispositions” [6]; for others, cultists’ praise of abject media objects and disdain for the noxious effluence that flows from the spigots of multinational corporations signals a powerful and much-needed FU to The Culture Industry.

Cult is celebratory, performative, and oppositional, as when Rocky Horror fans throw toilet paper at the screen and sing along to the transformational anthem to “Don’t dream it, be it” [7]; drawing from the twin traditions of cult and camp film performative criticism as pioneered by Manny Farber and Parker Tyler, it champions “self-expression as resistance to a form of culture for which the critic had only limited respect,” wielding “pop mythos as an assault weapon.” [8] Among the most fervent features of cult media performance is its adherents’ proselytizing; cultists counter their dismissal of the perceived mediocrities of mainstream culture by pointing potential initiates towards more transcendent alternatives. Cult clerics like the staffs of independent record-stores, comic-shops, book sellers, and DVD/VHS rental shops [9] steer neophytes away from the junk market-tested content that populates the algorithmic “Suggestions” of Amazon and Netflix (and the remaining big box stores) and towards the dark recesses of where the good shit resides, accessible only to the enlightened, illuminated few.

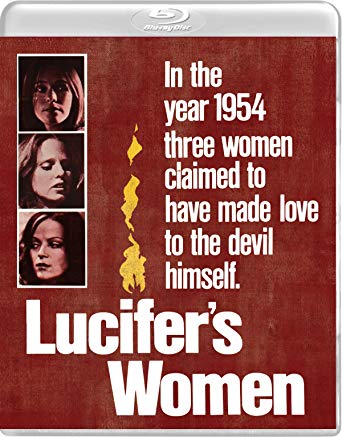

And so, I proffer unto you: Lucifer’s Women. Check it out:

Lucifer’s Women was released in 1974, shortly after the verdicts were returned in the Manson Family trials (1971, with the death sentences commuted to life imprisonment when California abolished capital punishment in 1972), The Exorcist stormed the box office (it was the #1 film of 1973, earning $193 million and vomiting pea soup onto over 21 million ticket-holders), Time magazine noted Satan’s big comeback in their cover story “The Occult Revival” (June 19, 1972), and Cosmopolitan offered sexy tips on five witchy love spells to try out on unsuspecting men (May 1973). [10] Writer-director Paul Aratow surfed the wave of occult interest with his film, but Lucifer’s Women was targeting a different audience than the mainstream; his exploitationer was liberally slathered with nudity, harnessing scenes of strip-joint dance routines and “love-making” (with a variety of exotic combinations of kinds and number of partners) destined for grindhouses (versus the red carpet of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where the cast, director, and writer of The Exorcist would find themselves in 1974).

One suspects that Lucifer’s Women probably hit the bull’s eye of its raincoat-crowd’s crotches, but the picture aims higher too; more than just flesh, the film delivers an entertaining, intriguing gloss on the dynamics of charismatic cult leadership. Its tawdry plot: An egomaniacal male academic—you probably know the type—writes an acclaimed biography of Svengali [11], but turns out really to be his reincarnated spirit; in order to keep his newly possessed body, he must sacrifice a young woman (a burlesque performer named, you guessed it, Trilby) at “the moment of orgasm” at a Satanic mass, officiated by (and engaging in sex with) the creepily Luciferian cult leader Sir Stephen. The real Wainwright falls in love with Trilby, and battles Svengali for the possession of his own body; meanwhile, Trilby’s landlord/drug-dealer/wannabe-pimp, Roland, tries to sever her growing fascination with Wainwright and lure her into a threesome with his current obedient, long-suffering steady girlfriend.

The plot of Lucifer’s Women funnels down concentric circles of charismatic power dynamics, with powerful men luring and manipulating servile women, in a pattern repeated from the (real-life) Manson Girls to the branded TV stars of Keith Raniere’s NXIVM. Sir Stephen humiliates Mary, a female initiate who resembles a hippie-chick Manson Girl down to the mark in the middle of her forehead, in the film’s most shocking scene, by having her kiss his feet while he pantomimes showering her with his urine. The film’s Alpha Males ultimately square off against each other, with Roland losing (his life) to Svengali, Svengali subordinating his will to Sir Stephen, and Sir Stephen submitting himself to Satan during a Black Mass. But the film suggests that powerful, self-assertive femininity might actually overpower fragile male dominance and cult leadership: Trilby and Mary turn the tables on the Demonic Duo of Svengali and Sir Stephen, destroying their plans for eternal malevolent life. The Satanic Cult may be seductive—during a romantic dinner-date, Trilby confesses to Wainwright/Svengali that “the kind of man that has power over women” is “everybody’s fantasy”—but is no match for a confident woman. [12]

Cultist consumers enjoy connecting dots between outré artifacts; working through the networks of weirdos both to each other and to their interfaces and overlaps with the mainstream is a cultish joy of sects. Lucifer’s Women does not disappoint on this score. The film gets much of its cult-cult cred from the participation of Anton LaVey, the infamous founder of The Church of Satan (and notorious publicity hound), who supervised the film’s Black Mass sequences, lending them theatricalized, camp-adjacent (in)authenticity. The same year that Lucifer’s Women hit theaters, LaVey inducted Sammy Davis, Jr. into The Church of Satan, based in part on the actor’s 1973 busted NBC pilot about the comic travails of a demon trapped on Earth, Poor Devil. Paul Aratow, the writer and director of the film, found multiple tracks to fame after this film. Aratow bought the rights to a couple of Will Eisner’s classic comic-book characters to produce the ABC pilot for The Spirit (1987) and the schlocky Tanya Roberts vehicle Sheena (1984); he founded the Berkeley restaurant that launched “California Cuisine,” Chez Panisse [13]; and he taught comp lit at UC Berkeley. But the kind of people who watch flicks like Lucifer’s Women may know him best from his highbrow-sleaze antique photography coffee-table collection, 100 Years of Erotica: A Photographic Portfolio of Mainstream American Culture from 1845 to 1945; Aratow shrewdly has Trilby flip through a copy of his recently published book and become aroused—a hilariously self-promotional, self-pleasuring moment of product placement.

Philip Toubus, who plays the lowlife whose pimp aspirations get squashed (along with his body, under the wheels of a limo) by Svengali, began his career as Peter in Norman Jewison’s big-budget musical Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) but later found his talents (and his unique anatomy) more in demand in hardcore pornography; as Paul Thomas, his IMDb page is hundreds of titles long. Gangly, weird-bearded Larry Hankin plays charismatic Svengali; you’d recognize him as the guy who plays “Kramer” in the pilot-within-a-show that Jerry and George sell to NBC in the meta fourth season of Seinfeld. And a quick look below-the-line yields a familiar name as the film and sound editor; working his way slowly from sleaze to the red carpet is David Webb Peoples, whose screenplays include Blade Runner, 12 Monkeys, and Unforgiven.

By the middle of the 1970s, the national interest in the occult hadn’t waned; simultaneously, the cult movie phenomenon was still in its youth. Lucifer’s Women may have opened and closed in 1974, but its life as a cult-cult artifact was far from over; its remains would soon be resurrected in a different form, for a different medium. What sort of dark arts were involved in its mysterious rebirth?

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screengrab.

2. Available on Vinegar Syndrome’s website.

3. Author’s screengrab.

4. Author’s screengrab.

5. Available on Abe Books’ website.

- Sconce, Jeffrey. “‘Trashing’ the Academy,” Screen 36.4 (Winter 1995): 374. [↩]

- Mathijs, Ernest and Xavier Mendik. “What Is Cult Film?” In The Cult Film Reader, Ed. Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2008): 4. [↩]

- Telotte, J.P. “Beyond All Reason: The Nature of Cult.” In The Cult Film Experience, Ed: J.P. Telotte. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991): 15-16. [↩]

- Hunter, I.Q. Cult Film As a Guide to Life. (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016): XV. [↩]

- Jancovich, Mark. “Cult Fictions: Cult Movies, Subcultural Capital and the Production of Cultural Distinctions,” Cultural Studies 16.2 (2002): 320. [↩]

- Jancovich, Mark, Antonio Lazaro Reboll, Julian Stringer, and Andy Willis. Defining Cult Movies: The Cultural Politics of Oppositional Taste. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003): 2. [↩]

- … or like the Rajneeshees singing along to “We All Live in the Orange Submarine,” Jonestown members performing in skits and dance routines, Synanon members playing The Game, Manson Family members playing home invasion/furniture rearranging Creepy Crawling games, or … [↩]

- Taylor, Greg. Artists in the Audience: Cults, Camp, and American Film Criticism. (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999): 68-69. [↩]

- I’m fortunate enough to live in Portland, Oregon, where these shrines to cultdom still exist; if you’ve got some of these in your neighborhood, please support them while you can! [↩]

- To offer a handful of moments of pop cult culture among many, many others of the era. [↩]

- Svengali was, of course, a character in George du Maurier’s Gothic novel Trilby, but I’m not sure the audience for Lucifer’s Women fretted much about the seducer’s leap from fiction into reality. [↩]

- … unless you stick around for the final ending of the film, which is a trick ending that repudiates this entire sentence. [↩]

- Co-founder Alice Waters has been its Executive Chef since 1971; Aratow was its first chef de cuisine. [↩]

I have been searching about delete POF account then finally, when I read this article I get to know the correct information about it and I found this information is relevant. You have an ample amount of knowledge and that describes it very clearly and I thank you for giving me this type of knowledge and it helps me a lot.