“The Game on Top of the Game”: Navigating Race, Media, and the Business of Basketball in High Flying Bird

Courtney M. Cox / University of Southern California

On the surface, it appears to be a film about basketball. Netflix’s High Flying Bird (2019) boasts the back of a jersey on its cover, the sneaker squeaks of the gym, and the voices of some of the National Basketball Association’s (NBA) real-life up-and-coming stars (Reggie Jackson, Donovan Mitchell, and Karl Anthony-Towns) interspersed as vignettes with the film’s scripted SAV Management, an agency representing professional athletes. The main character, Ray Burke (played by André Holland) is an agent representing NBA rookie Erick Scott, the first pick in the previous draft who has yet to play his first game due to a league-wide lockout. At first glance, it’s a version of HBO’s Ballers meant to be taken seriously; the viewer spends time following Scott navigate the financial pitfalls of being a young millionaire-to-be who hasn’t gotten his first check, while Ray maneuvers through a firm struggling under the weight of the lockout as owners engage in battle with a players’ union fighting on behalf of its athletes.

But close up, the film is a critical, albeit heavy-handed look at the global phenomenon of basketball and the racial and economic shifts which have shaped the game. Early in the film, old school coach Spence (Bill Duke) tells Ray, “There’s a reason why the NBA started integrating as the Harlem Globetrotters’ exhibitions started going international. Control. They wanted the control of a game that we play, we played better. They invented a game on top of a game.” The game on top is an ecosystem comprised of agents, television networks, marketing execs, and team owners who profit off of the spectacle of a majority-Black sport. Even Ray, a Black agent, is positioned outside of the power circle of his own firm and the greater “game” operating above the court.

Much of the film operates through smaller screens, filled with familiar faces and voices of TV personalities such as Skip Bayless and Shannon Sharpe, shows like TMZ, and tweets between players. The media isn’t a subplot of the film; it’s a major character. High Flying Bird focuses on the media’s role as a catalyst for both the actions of players, their families, and league representatives while simultaneously delving into the major media contracts between the NBA and TV networks, which comprise a large portion of the league’s annual revenue.

Ray’s ingenuity in concocting a plan to end the lockout is rooted in creating “something that they can’t bottle up,” after his former assistant asks if they’ve “run out of story” (in the same way one could run out of money). One fabricated Twitter beef and 24-hour news cycle later, a one-on-one hoops showdown on a community court between two rookies draws in millions of views to shaky cell phone video, proving they may be out of money, but aren’t yet out of story. The exclusive nature of an untelevised one-on-one game between two players yet to take the court in the NBA takes the social media posts of those at the game viral and results in the potential to create new exclusive streetball games—”lockout ball”—while negotiations continue. Ray schedules meetings with Facebook and yes, even Netflix.

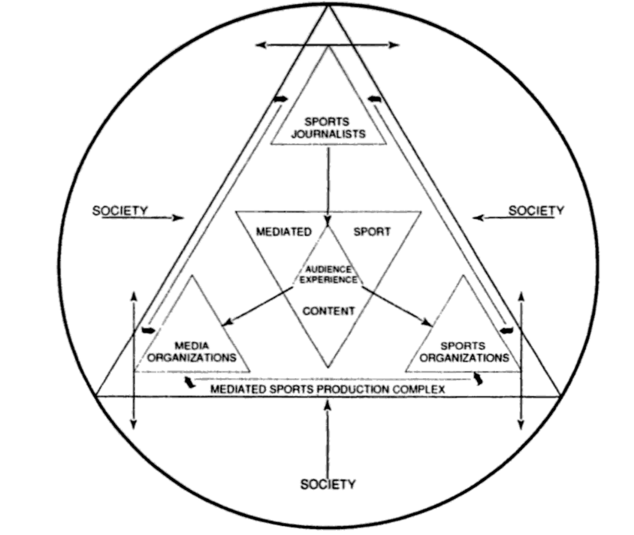

Watching the film, I couldn’t help but think of sport scholar Lawrence Wenner’s Transactional Model of Media, Sports, and Society Relationships. Wenner offered a blueprint of the “game on top of a game” in his canonical Media, Sports, and Society (1989). His visual representation of what has been called the sports-media complex (the interdependent relationship between sports and media) offers a bird’s eye view of the ties and tensions and between sports organizations, media conglomerates, and fans. [1]

During a lockout, it is particularly difficult to ascertain what’s going on within the “sports organizations” triangle, comprised of athletes, owners, league officials, and the players’ association. It is interesting that Wenner chooses to place athletes within this particular grouping rather than outside of it (a la “sports journalists” in their own triangle from “media organizations”). Sports fans may remember 2011-2012 as particularly fraught for player-league relations as three out of the “Big Four” U.S. men’s professional leagues faced lockouts across the National Basketball Association, National Football League, and National Hockey League. Jonothan Lewis and Jennifer M. Proffitt, in comparing coverage of a lockout in 2011 to the mid-1990s, found that the media continues to focus on many of the same major themes: a consumer focus (the fan as the ultimate loser in these labor negotiations), lockouts as a “millionaires vs. billionaires” problem (rich people’s problems), and the players as “gaming the system.” [2] High Flying Bird seemingly reifies this model throughout the film, locating athletes who wish to operate outside the league’s framework as deviant, or, as Ray defines it, “disruptors.” As negotiations between the players’ union and team owners stall, the concept of players and agents joining forces to create their own league and negotiate media rights deals feels like fantasy, even when housed within the realm of a scripted film. The concept of a lockout league is shopped around to interested media factions outside of the standard ESPNs, NBCs, and FOX offerings. Ray sets up meetings with Facebook and yes, even Netflix. “For a second,” Ray says, “I could see an infrastructure that put the control back in the hands of those behind the ball instead of those up in the sky box.” However radical this vision appears, the film captures how his eventual actions serve to move him socially and financially closer to sky box rather than realigning power to those on the court.

In the same way, it is fascinating to consider that this film, shot by director Steven Soderbergh in two weeks on an iPhone (with a working cut available within hours of completing shooting), also represents a shift in the gatekeeping of filmmakers and production in general. While shooting a film on a smartphone is nothing new (thousands of film students do this daily), Soderbergh offers a potential disruption because of his position as an established industry figure. However, like the normalization of streaming platforms and social media networks into the entertainment industry, these technological shifts do not inherently make these spaces more egalitarian; rather, they become embedded into the system (an Oscar nod, the ability to hire and retain top talent, etc.). Ray’s desire to collapse the game on top of the game merely resulted in a regulating mechanism to stifle any potential dismantling.

Ultimately, the threat of reasserting the “control” that Coach Spence references at the beginning of the film is enough to end the lockout; Ray, in an attempt to assert himself within this game on top of a game, uses his position—along with the players as pawns—to change the power structure, if only for a moment. He, in turn, is rewarded, but once again absorbed into the larger framework. At best, he can only shift the model for his own benefit, not destroy it entirely.

Image Credits:

1. High Flying Bird attempts to capture the business of basketball through agent Ray Burke (André Holland) and Erick Scott (Melvin Gregg). (author’s screen grab)

2. The media play an integral role in the film’s plot development. (author’s screen grab)

3. In the late 1980s, Lawrence Wenner offered this model to explain the symbiotic relationship between sports, media, and society. (author’s screen grab)

4. Ray’s attempts at a radical readjustment of power merely operate as a means to embed him further into the institution of corporatized sport. (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Wenner, L. A. (1989). Media, Sports, and Society: The Research Agenda. In Media, Sports, and Society (pp. 13–48). Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [↩]

- Lewis, J., & Proffitt, J. M. (2013). Sports, Labor and the Media: An Examination of Media Coverage of the 2011 NFL Lockout. Labor Studies Journal, 38(4), 300–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X14522324. [↩]

Thank you for visiting Hi-Lo Industrial Trucks Co. Since 1946, Hi-Lo Industrial Trucks has been serving the needs of southeastern Michigan businesses as a small business continuously striving to serve the needs of a growing community. We Offer Forklift Service, Fork Lift Repairs, Forklift Rental, Sales & Parts to cities around Detroit (MI), including: Detroit, Warren, Sterling Heights, Ann Arbor, Livonia, Dearborn, Canton, Westland, Troy, Farmington Hills, Southfield, Waterford, Rochester Hills, Pontiac, Taylor, Royal Oak, Dearborn Heights, Novi, Redford, Roseville, Lincoln Park, Eastpointe, Madison Heights, Southgate, Garden City, Inkster, Oak Park, Allen Park, Wyandotte, Romulus, Ypsilanti, Hamtramck, Ferndale, Monroe, Auburn Hills, Trenton, Birmingham, Wayne, Hazel Park, Mount Clemens, Grosse Pointe Woods, Highland Park, Berkley, Fraser, Wixom, Harper Woods, Woodhaven, Riverview, Clawson, Grosse Pointe Park, Rochester, New Baltimore, South Lyon, Grosse Ile, Ecorse, Melvindale, Beverly Hills, Farmington, Grosse Pointe Farms, River Rouge.