Five Ways I’ve Defined Fan Studies

Jenny Keegan / Louisiana State University Press

When you make a career in fan studies, I’ve learned that you must get used to defining it quickly at parties (and conferences, sob). Four years after reading my first fic and twentyish months after arranging for fan studies to be (part of) my job, I still haven’t perfected my elevator pitch, in part because I like the field so much it’s hard to be succinct. But here’s what I’ve got.

1) “No, not that kind of fans.”

Sometimes people go “Fans? Like, pfft-pfft-pfft, fans?” or make spinny hand gestures at me, which usually means they knew exactly what kind of fans I was talking about and find it ridiculous that there’s a discipline for that. Fan studies scholarship often begins by defending its right to exist, and while I wish that authors didn’t need to issue such disclaimers, I can’t deny that the field comes in for its share of neglect and derision.

A recurring theme in much of fan studies is the outsider status of the communities under study—they’re women, they’re nonbinary, their tastes are weird and fringey, they’re getting queer sex all over your faves. They’re under attack from the lawyers of wealthy creators because nobody’s gay in Star Wars; they’ve been offered a place at the table, as long as they play by the rules (they won’t) and it doesn’t turn into a PR disaster for the company (it will).

As fandom moves out of the margins—as fan writers grow up and gain access to the keys of the media kingdom—it becomes harder to make the case for fannish marginality as a cornerstone of fan studies. The lines between canon and affirmational fandom and transformational fandom, never all that firm to begin with, are collapsing all over the place.

2) “It’s the study of how people interact with things they like.”

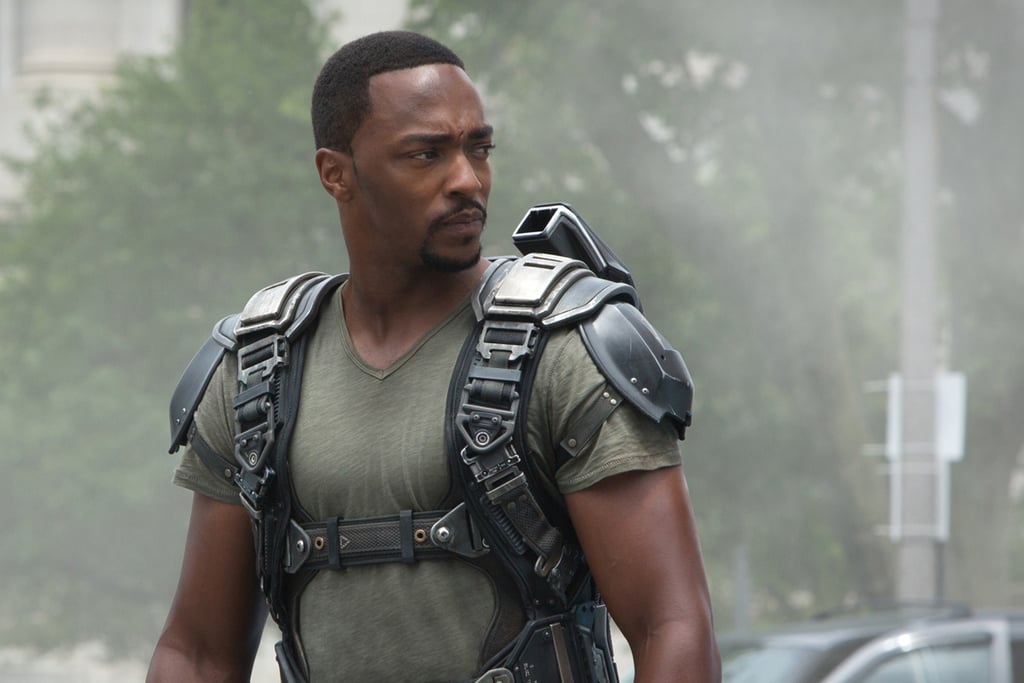

This is my best, most common response, because it encompasses a wide range of fannish activities, from literary criticism to cosplay, and the other person does not need to ask follow-up questions in order to feel they have understood my answer. But I’m also unhappily aware that things they like is an imperfect descriptor. I like the Captain America movie trilogy enough to want more time with those characters, yet not so much that I wouldn’t prefer to spend my weekends reading fics about Sam Wilson, the obviously best Avenger (do not @ me). If there’s one thing transformative fandom knows how to do, it’s love a thing while wanting it to be better.

Even so, this response gets at the scope of what fan studies is becoming. The differences between types of fandom don’t hold up to much scrutiny if you take the patriarchy out of the equation. (Which, can we just do that? Would it be okay to just topple it already?) As Kavita Mudan Finn and Jessica McCall note,

In a world of undead authors and readers unsure of their own critical authority, fanfiction provides a unique avenue in which to actively undercut the positivism of traditional approaches to interpretation. [1]

The difference between a solid meta and a piece of literary criticism is gender, class, money, access; but both arise from the writer’s desire to engage with, grapple with, a piece of work that they like and find interesting.

3) “It examines how people participate in the things they care about, and especially how they resist and rework those things.”

Or, the slightly more detailed version of #2. I like to follow this up with the example of pro football fans’ responses to NFL players protesting police brutality during the national anthem (including Eric Reid, who’s out of LSU!). I use this example because I’m from South Louisiana and we have a brand to maintain; because it’s a situation that a lot of people know a little about; and because I like to shake up the idea (that other disciplines have) that fan studies only cares about girly stuff. Or to put it the other way around, I like to get my girly-stuff-fan-studies cooties all over everything else.

As with all my other answers, this one dissatisfies me. I am interested in fandom-as-resistance, but I am also aware that fannish resistance in one area is no protection against fannish prejudice in another. [2] To return to the Captain America example, just toddle over to AO3 dot org and you will find a wealth, a cornucopia, of fic that reimagines Captain America as queer. But if you desire to read stories starring Sam Wilson, the obviously best Avenger (yeah, I’m doubling down on this), you will find yourself wading through a lot, a lot, of stories in which Sam Wilson is only there to provide emotional support to the white Avengers.

4) “It’s a subdiscipline of [insert field here].”

No matter what I put inside those brackets, I can’t help feeling that I’ve told a filthy lie. At the recent Fan Studies Network–North America conference, discussion turned to making more space for fan studies within the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. Well and good as far as it goes, but a literary fandom scholar pointed out that they live under the umbrella of English departments, and don’t have access to SCMS events and resources. Liking things is not confined to a single academic field, not media studies or communications or literary studies, which makes it tricky to find a disciplinary definition for fan studies.

I suspect, though, that the discipline’s liminal status within the academy has given it some of the same strengths that outsiderhood has given to fandom. While literature and film and cultural studies gatekeepers weren’t watching, students who grew up in fandom crept into their departments and started chipping away at the distinctions between the serious (bell hooks, Theodor Adorno) and the decidedly unserious (Johnlock conspiracy theories, Teen Wolf ABO fanfic). Standing within fan studies and surveying the terrain, it seems impossible that fan studies won’t have its hooks into every university department in a few years’ time.

Because the true answer I want to give, when someone asks me to define fan studies, is one that I’ve never actually used:

5) “It’s the field that’s going to remake the Humanities.”

Image Credits:

1. A picture of the Marvel Cosplay meet-up taken at San Diego Comic Con in 2013.

2. Anthony Mackie’s character in the Marvel Extended Universe, “The Falcon.”

3. Colin Kaepernick (right) and Eric Reid kneeling during the national anthem in a stadium filled with fans.

References:

- Finn, Kavita Mudan and Jessica McCall. “Exit, Pursued by a Fan: Shakespeare, Fandom, and the Lure of the Alternate Universe.” Critical Survey 28, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 27–38. [↩]

- Do yourself a favor and follow Stitch’s Media Mix for consistently insightful critiques of fandom racism. [↩]

This was really a nice way for us.