Punk, Disco, Porn—The Deuce ’77—Part 1

Matthew Tchepikova-Treon / the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

<

Beginning in 1977, five years on, Season Two of The Deuce extends the show’s thoroughgoing investigation of the sex industry in porno-chic New York City. HBO first advertised the new season with an image of late-1970s 42nd Street under a caption that read: “Punk, disco and porn.” Beyond signaling a certain pop culture milieu, these three words signify a sort of cipher for the show’s complex audiovisual world-building techniques. Because, from punk shows to ad hoc discos to female-directed arthouse porn to a cabaret-styled gay bar battling “noise complaint”-based zoning restrictions, The Deuce continues to present a story largely focussed on the labor of (sub)cultural production, the sonic production of social spaces, and the power dynamics of an exploitative capitalist logic working to absorb or silence them.

Punk. The word itself reaches back centuries and even carries with it an etymological link to prostitution. In Shakespeare’s 1603 play Measure for Measure, a young woman engaging in a bed-trick[2] tells an inquiring duke that she is neither a wife, widow, nor maid. The duke replies, “Why are you nothing then?” Another man then follows the duke’s misogyny-whisked grouse with: “My Lord, she might be a Puncke.”[3] Centuries of varied utterances transformed the word from prostitute into a verb denoting the act of sodomy, then referent for a male homosexual, and eventually a general signifier for social ‘trash’ and debauched street youths, etc.[4] Seventies punk culture, with its embrace of aesthetic excess, social transgressions, and explicit gender reformations, embodied all aspects of the word, including its attendant ideological contradictions. But further still, as Adam Krims argues in his study of music and cities transformed by “post-Fordist” modes of capital accumulation, Seventies punk and new wave also “announced different perceptions of city life, in which squalor and class-based rage could no longer be denied or contained.”

Abby’s Jukebox

The Deuce set up its engagement with punk’s historical future back in 1972, through a scene in Season One involving NYC musician Garland Jeffreys at the Hi-Hat performing the Continental organ-driven classic “96 Tears,” a song written and originally recorded in 1966 by ? and the Mysterians, whose sound and style motivated Creem magazine’s Dave Marsh to first use the term “punk rock” (in popular print) while describing the band in 1971, years after hearing them live.[5] During the scene, Abby mentions to Vincent that she first heard Jeffreys and his band playing a rent party down at St. Marks Place. Along with calling up the origins of “punk” in early rock criticism, this pop culture citation looks ahead to the first wave of punk bands who would soon populate the East Village, while also nodding back to 1920s Harlem and the city’s long tradition of underclass tenants organizing early blues and jazz apartment shows to battle slumlording tactics and help pay rent.[6] Such a moment demonstrates not only The Deuce’s intricate use of music-history-cum-urban-geography, but also works to identify the social stakes involved for the show’s characters.

In 1977, with the music’s antibourgeois teeth now on full display, Season Two finds Abby managing the Hi-Hat and operating the bar as a material nexus of NYC punk’s “subcultural capital” now flowing through Manhattan alongside political influence and boffo profits from prostitution and porn. As Sarah Thornton reminds us, subcultural capital always emerges from particular social spaces,[7] and in this season’s first episode, Abby uses the bar before opening hours to meet with a young self-described “feminist dancer”[8] experiencing “labor hassles”—which Vincent dismisses as “Chairman Mao bullshit”—after organizing strippers at the Metropole Cafe near Times Square to stage a three-day walkout. Abby suggests that they “book a band, do a fundraiser” at the bar and donate cover charges to the dancers for lost wages during the strike. After their meeting, Abby goes to the jukebox, now stocked with period-perfect records, and plays “Prove It” (1977) by Television, Richard Hell’s band forever associated with the forging of New York punk at CBGB. Throughout the season, we additionally hear The Runaways (“Born To Be Bad”), Iggy Pop (“Sister Midnight”), Wire (“1 2 X U”), Siouxsie and the Banshees (“Hong Kong Garden”), T. Rex (“The Slider”), Wyldlife (“The Right!”), The Patti Smith Group (“Ask the Angels”), the Ramones (“You’re Gonna Kill That Girl”), X (“Adult Books”), etc. Later in the same episode, recalling the Hi-Hat’s early punk permutation by way of “96 Tears,” we similarly hear a band perform the 1976 underground hit “New Rose” by The Damned.[9] The first of the London punk bands to tour the U.S., The Damned did in fact perform at CBGB in 1977, but the scene’s effectiveness comes in part from the (unanswered) question whether or not this is The Damned or another band covering their song.

On the level of formal aesthetics, Abby’s jukebox and Hi-Hat concerts underscore how, through deeply informed diegetic sound design, The Deuce uses punk music as a means of sonic verisimilitude that remains attuned to the labor involved in punk’s radical cultural production writ large. However, this is no utopian enterprise. The Deuce effectively utilizes punk culture by aligning the music’s inherent contradictory impulses with, rather than against, the hierarchical forces of capitalism at work throughout the show. After all, the same 1970s media coverage that originally hyped punk’s moral panic to sell newspapers not only likewise helped sell records, but Dick Hebdige, in his classic subcultural study of punk style and society, even dates the commencement of this coverage to a particular incident in 1976, when a young woman was “partially blinded by a flying beer glass” during a punk show in London’s own red-light district.[10] The Damned performed at that same show.

Eating Cannibals

In a 1979 Village Voice column examining the shared aesthetic between NYC art-punk bands and “new wave” filmmakers (who also often shared exhibition spaces), J. Hoberman observed: “Drifting across the Bowery, fallout from the 1977 punk ‘explosion’ continues to spawn art-world mutations.”[11] And part of what Hoberman identified was a politically powerful style “shot through with fantasies of punishment and revenge” and sexual violence he compared to “the aestheticized violence of 42nd Street,” referencing both the Deuce proper and the fast-burning exploitation films of the era that circulated through its so-called grindhouse theaters. By the end of the piece, Hoberman concludes that punk’s shared cultural project, predicated on shock-and-awe absurdity, had perhaps unintentionally produced a form of social realism instead. We hear a sonic representation of Hoberman’s suspicion during a particularly affective scene late in The Deuce Season Two.

Working with former prostitute, Dorothy, to address the dangerous conditions of sex work on the streets, Abby decides reluctantly to use payout money from Vincent’s mob-backed sex parlor to fund free health clinics for the women. In due time, however, a group of pimps murder Dorothy once her work becomes bad for business. Soon after, another prostitute walks into the Hi-Hat and through tear-glassed eyes silently communicates Dorothy’s death to Abby behind the bar, the camera trained on these women’s faces. In this moment, we hear only the erratic fits of electric feedback and metallic dissonance from a punk band checking their sound off screen.

Image Credits:

1. The Deuce Season Two Poster Art.

2. Scene from The Deuce, Season Two, Episode 1, “Our Raison d’Etre.” (author’s screen grab)

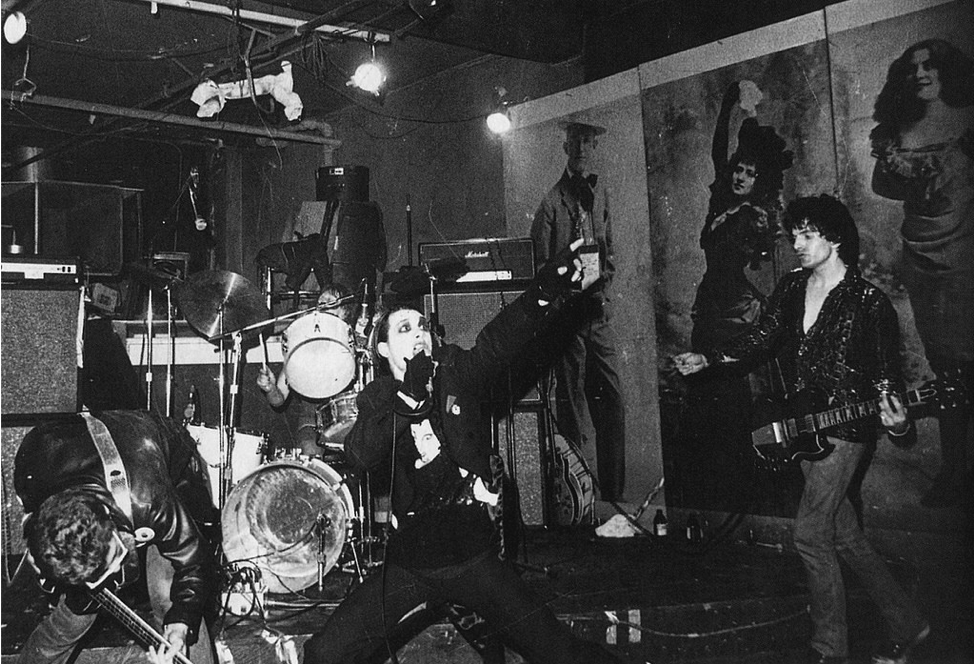

3. The Damned playing at CBGB in 1977. Photo by Ebet Roberts.

4. Scene from The Deuce, Season Two, Episode 5, “All You’ll Be Eating Is Cannibals.” (author’s screen grab)

5. Scene from The Deuce, Season Two, Episode 9, “Inside the Pretend.” (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Matthew Tchepikova-Treon, “What Kind of Bad?: Curtis Mayfield and The Deuce,” Jump Cut, no. 58 (2018). [↩]

- A common plot device in the playwright’s early tragicomedies, see: Julia Briggs, “Shakespeare’s Bed-Tricks,” Essays in Criticism, Volume XLIV, Issue 4, 1 (October 1994): 293–314. [↩]

- William Shakespeare, Neil Freeman, and Paul Sugarman, The Applause First Folio of Shakespeare in Modern Type (New York: Applause, 2001), 81. [↩]

- Also see: Tricia Henry Young, Break All Rules!: Punk Rock and the Making of a Style (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1989), 7. [↩]

- Creem, Vol. 3, No. 2 (May 1971). For Marsh, the value of the band’s “new sound” paradoxically came from its return to a street-inspired form of rock before the age of arena-sized spectacles. Charlie Gillett makes the anachronistic suggestion that “96 Tears” might have been “the last pure punk record,” probably on account of Marsh’s original claim. See: The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 35. [↩]

- See: Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 89-125. [↩]

- Sarah Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1996). [↩]

- The show’s writers here artfully gesture toward second-wave feminism’s important debates between anti-pornography activists and anti-censorship feminists concerning the cultural forms and social functions of porn. For a detailed account of this history and a thorough analysis of these debates, see: Linda Williams, Hardcore, 16-30. [↩]

- In a 1982 Rolling Stone interview with Greil Marcus, Elvis Costello, when asked about his cultural and discursive associations with punk music, said, “The Damned were the best punk group, because they had no art to them… They were just—nasty.” [↩]

- Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Methuen, 1979), 142. [↩]

- J. Hoberman, “No Wavelength: The Para-Punk Underground,” Village Voice, May 21, 1979. [↩]