Flowing Forms, Pts. 1 & 2: Real and Virtual Bodies

Jennifer Lynn Jones / Indiana University

|

Media presuppose bodies. In their role as moderators, media act “in-between” for bodies: translating signals, distributing content, connecting people. Media are thus responsive to bodies, and likewise bodies are responsive to media, with both transforming through their interactions, bridging the physiological, the technical, and the cultural. Bodies are therefore more than just receptors for media content but constitutive to media forms and necessary for media praxis, arguably performing like another platform for media convergence. However, bodies remain undertheorized in media studies outside of representation. As such, this query seeks responses to illuminate how media and bodies affect each other, especially through moments of significant cultural, industrial, and technological change. Specifically, how do changes in media and bodies correspond? How do they shape each other? How do these connections and their attendant transformations relate to hegemonic systems, whether legitimating operations in media or identity hierarchies in bodies? What exchanges between bodies and media are critical to consider in contemporary culture, and what must be further examined from the past? Why do these interactions matter, and how might they affect experiences of both media and embodiment in the future? *Jennifer Lynn Jones, Indiana University *denotes panel convener |

I start with this quote from Rachael Ball’s response to my “Flowing Forms” query as the interrogation it suggests resounds in my review of the query’s two roundtables. Using another’s words also seems evocative of the concerns of the query on the connections between bodies and media, and the complications in my task to summarize multiple contributions at a conference through the voice of one person. As a medium for these conversations, I intend to channel the most persistent themes and conduct lingering questions from what still seems buried there.

In my review of the roundtables—culled from written responses, session discussions, and hashtagged tweets—I perceive four overlapping themes: boundaries and limits; materiality; identity, power, and care; and utopic versus dystopic effects. The first involves the very division of the roundtables between “real” and “virtual” bodies. It questions the lines between bodies and media, between natural and “unnatural” or acceptable and unacceptable bodies, how far is too far, and why those demarcations matter. Some of those are ethical as Nicole Strobel examines in Vice’s exploitation of marginalized “radical embodiments” to expand its brand. Others are constitutive, as Adam Resnick notes in his estimation that speculative fiction often limits the potential of trans- and posthuman forms.

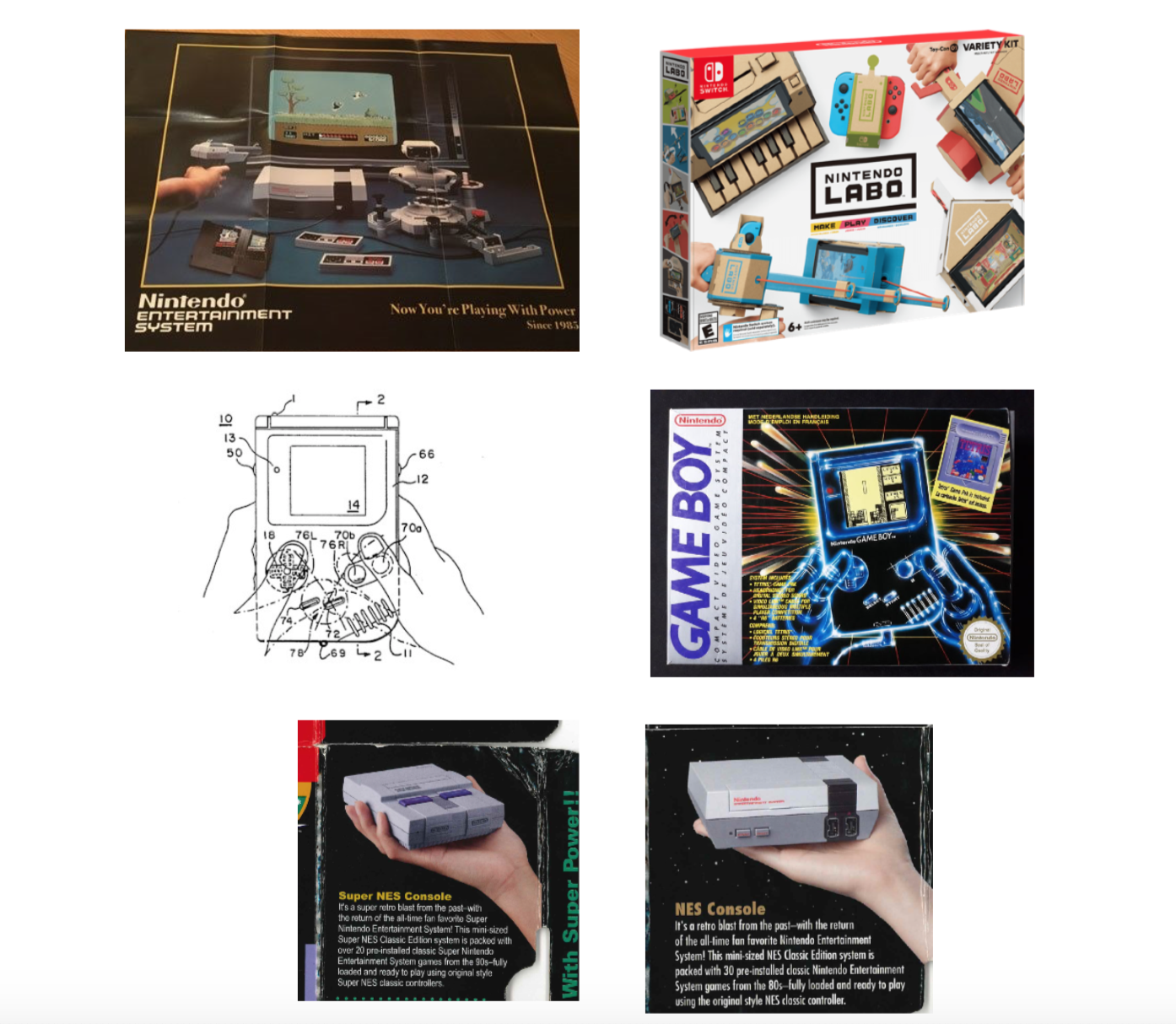

Next, contemporary concerns with digital media and virtual experiences often overshadow considerations of materiality in the relationship between bodies and media. Ball’s invocation of special effects bodies in the multiplatform true crime genre helps to “reinscribe biological materiality of all kinds into our interaction with both digital and analogue media widely conceived.” Daniel Reynolds accentuates materiality through the use of hands holding game controllers in Nintendo advertising, arguing that this portrayal “levels them up” as constitutive parts of a shared system.

The whiteness of those hands “matters” here as well, connecting to the next theme of power, identity, and care. Maya Iverson’s response centers media archives in (re)constructions of African-American identities as “we are still struggling to overwrite and annotate how our bodies are marked by the condition of social death” through ongoing oppressions. My study of the somatic convergence of actress Chrissy Metz with her This Is Us’ character Kate through weight loss reveals how makeover logics lead to a transmediation of the show.

Last but not least, traces of the utopic and dystopic are omnipresent, interrogating how these connections between bodies and media create meaningful changes to lived conditions, even beyond the human. Hyo Jung Kim looks at how digital media technologies give users “renewed cognition of the world and redefine the boundaries of their physical body” as a kind of “imaginative subjectivity” that can be used to “reframe (their) agency in relation to the power structure,” like remixing Trump singing “Despacito” in a tactical “playful liberation.” Melissa Avdeeff posits that “(a)s new bodily alternations become possible in an era of post- and transhumanism, it will become increasingly important to study the ways in which media… imagines and perceives of a ‘natural’ body, and how those depictions influence dominant understandings of those potential futures,” using Björk’s “Utopia” video as one media example that envisions the potential of human evolution into nature.

What questions remain to raise? One area for further consideration is political economy. How do the power dynamics in material economic relations affect these entities and their connections? Another that was present but could have gone farther involves identities and boundaries. In her written response, Avdeeff questions the definition of a body, and others in attendance at the roundtables echoed it, especially in relation to race, gender, and disability. The choice of the term “body” is provocative in that way, suggesting a corpus devoid of identity markers, but of course, still structured by dominant meanings of identities that “matter.” Dissecting such constructions and their relationship to media is at the heart of the “Flowing Forms” query and given the generative response to the query will hopefully be ongoing.

Image Credits

1. Chrissy Metz and Carla Hall on The Chew

2. Hands holding game controllers, author’s screen shot

3. From Bjork’s “Utopia” music video