Community Guidelines and the Language of Eating Disorders on Social Media

Ysabel Gerrard / The University of Sheffield

All social media platforms have a set of community guidelines which lay out, in ‘plainspoken’ terms, how they want their users to behave and what kinds of content they think are (and are not) acceptable. [1] They have rules against supporting terrorism, crime and hate groups; sharing sexual content involving minors; malicious speech, amongst other acts that aim to threaten or damage certain parties, to use Tumblr’s words in the quote above. But some of these rules are harder to justify and enforce than others.

For example, in 2012, and in response to a Huffington Post exposé about the ‘secret world of teenage “thinspiration”’ on social media, Instagram, Pinterest and Tumblr released new guidelines about content related to eating disorders, like anorexia and bulimia. They said they would draw lines between accounts and posts that ‘promote’ eating disorders and those aiming to ‘build community’ or facilitate ‘supportive conversation’ about the issue.

Yet this promotion/support dialectic indicates a misunderstanding of online eating disorder communities, and in what follows I present a series of examples to provoke a discussion about the language used in social media’s community guidelines.

Locating the ‘Pro’ in ‘Pro-Eating Disorder’

The language of promotion used in community guidelines was likely influenced by the online pro-eating disorder (pro-ED) movement, formerly found in the homepages, forums and chat rooms of a pre-social media Web. The term ‘pro’ is commonly (and insufficiently) understood to denote the promotion of eating disorders, but internet users have always varied in how they operationalise this term. For example, some adopt it as an identity to break away from the medicalisation of eating disorders; some use it to embrace eating disorders and break away from stigma; some use it to create spaces of support for others; some want to find likeminded people; and yet others – though these people are said to be in a minority – use it to promote and encourage harmful behaviours in others.

While some posts do straightforwardly promote eating disorders – like ‘meanspo’ agreements, short for ‘mean inspiration’, where users agree to post cruel comments to one another to encourage starvation and weight loss – a lot of it blurs the line.

The ‘What Ifs’ of Reading Images

Several internet researchers, myself included, have shown how social media users savvily work around platforms’ rules. For example, after the Huffington Post exposé, Instagram stopped returning results for ED-related hashtag searches like #proana, but users coined lexical variants to evade moderation (e.g.,#proana became #proanaa). In a recent paper I showed how users now avoid using hashtags or other textual clues to align their content with pro-ED discourses, meaning the work of deciding whether a post promotes eating disorders has become even harder.

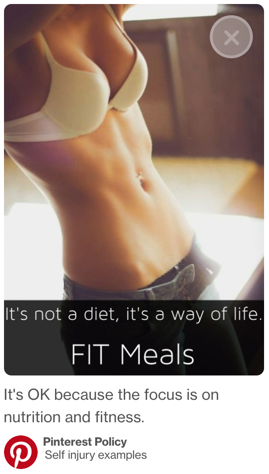

For example, in its community guidelines, Pinterest gives users an example of an image that does not, in its view, promote eating disorders. They claim this image is acceptable because ‘the focus is on nutrition and fitness’:

But what if Pinterest removed the text overlay – ‘it’s not a diet, it’s a way of life. FIT meals’ – and simply depicted a slender female body, perhaps in black and white, a common visual aesthetic in online eating disorder communities? Why is this level of thinness acceptable? And how do we decide if it’s ok to promote certain diets and meal plans and ‘way[s] of life’ above others?

Here are some more examples, taken from Instagram: [2]

Would you say the above images promote eating disorders? Yes, the people’s bones are outlined and emphasised in the framing of the images, but when do they become too bony, to the point where these images are read as the promotion of anorexia or similar? Does the act of posting these images alone constitute promotion? And what might happen if these were male bodies? These are just some of the many questions that could be asked about the challenges of drawing the line between harmlessness and promotion.

‘Things You Might Love’: The Gender Politics of Recommendation Systems

Another way content circulates on social media is through algorithmic recommendation systems. In short, platforms show you what they think you want to see. This is especially true of Pinterest, which arguably functions as more of a search engine than a place to make deep connections with other users. But what we don’t know is how Pinterest and other platforms decide which posts have similarities to others.

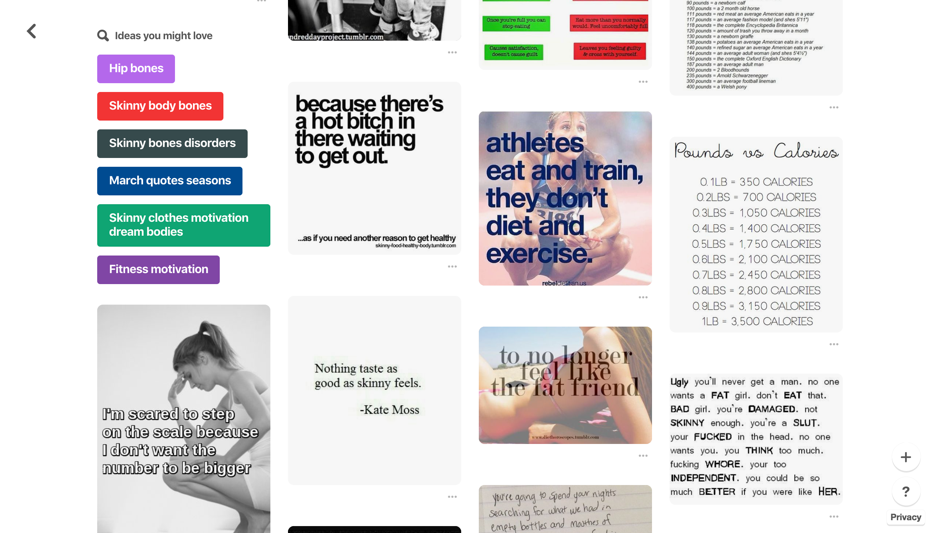

Take the below screenshot of Pinterest recommendations as an example. I found these images by searching for ‘thinspo’ on Pinterest (a term that has long been linked to eating disorders) and selected the first image, which had a black background and read ‘need to be skinnier for summer’ in large white letters. Pinterest listed other ‘ideas’ I ‘might love’ underneath the post:

Different kinds of content are being conflated here, as images about athleticism and getting ‘healthy’ sit alongside suggestions for ‘skinny bones disorders’. Some of these images have ‘no specific connection’ to eating disorders and yet they have been re-contextualised within a new environment that makes them seem problematic. [3] So which of these posts would you say promote eating disorders, which don’t, and why?

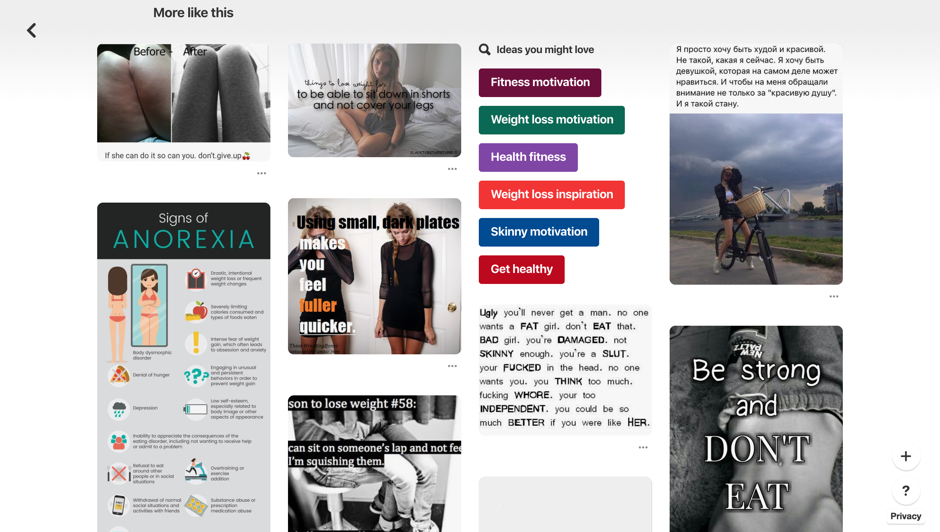

I then selected a different image – the ‘nothing tastes as good as skinny feels’ quote shown in the post above – and these were my recommendations:

Again, which of these posts do you think promote eating disorders? Are any of them bad enough to be removed from Pinterest?

What’s interesting to me is that Pinterest’s suggestions for ‘fitness motivation’, ‘get[ting] healthy’ and spotting the signs of anorexia are mixed in with posts urging readers not to eat, and meanspo quotes like ‘not skinny enough’ and ‘you’re a slut’. Pinterest is thus conflating content related to eating disorders with posts about thinness (health, fitness, nutrition, diet plans, weight loss, and so on), reinforcing a longstanding and narrow view of what an eating disorder is (hint: anorexia isn’t the only one, and not everyone wants to lose lots of weight).

Algorithmic personalisation is making it even more challenging to draw the line between posts that promote EDs and those which promote other aspects of female body control, potentially having material effects on how people find content related to eating disorders and learn about what they are.

Getting It Right

Only a minority of users in pro-ED spaces actually promote eating disorders, yet platforms borrow this language and use it to justify their decisions about content moderation. This is precisely why we need more insight into platforms’ decision-making processes: how do rule-makers define ‘promotion’, and how is this kind of language operationalised by those whose job it is to scrub objectionable content from social media (the commercial content moderators (CCMs))?

Sometimes social media content moderation is necessary and I respect the difficulties companies face as they grapple with their desire to provide spaces for self-expression while needing to set some limits. But if platforms are going to take on the moral work of deciding what content should stay or go, especially when it comes to users’ health, they need to make sure they get it right.

Image Credits

1. Tumblr’s Community Guidelines

2. Pinterest’s Community Guidelines

3. Author’s screenshot of an anonymised user’s Instagram post

4. Author’s screenshot of an anonymised user’s Instagram post

5. Author’s screenshot of an anonymised user’s Instagram post

6. Author’s screenshot of Pinterest recommendations

7. Author’s screenshot of Pinterest recommendations

Please feel free to comment.

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media. Yale: Yale University Press, p.76. [↩]

- These images are taken from the same dataset used in my latest paper: Gerrard, Y. (2018). Beyond the hashtag: circumventing content moderation on social media. New Media and Society. 1-20. [↩]

- Vellar, A. (2018). #anawarrior identities and the stigmatization process: an ethnography in Italian networked publics. First Monday. 23(6), n.p. [↩]