In Memoriam: Black Twitter and TV Cancellations

Jacqueline Johnson / University of Texas at Austin

Throughout 2017, black audiences grappled with news that black produced and black led shows were being cancelled one by one. Survivor’s Remorse, Pitch, Underground, and The Get Down were just some of the television series that met their ends in 2017. Though many television fans experience relief or dismay when networks announce which shows they are moving forward with, black audiences have demonstrated that their investment in keeping black shows on the air extends past their positive affective relationship to the program; there are ideological stakes. Because black viewers have had to navigate the absence of representation as well as images steeped in racist stereotypes, black audiences’ commitment to black shows (which I define here as shows with black creators or producers and/or black lead actors) frequently extends past other groups. This commitment has been illustrated in black media outlets, however, black adoption of the micro-blogging platform Twitter has demonstrated the myriad ways black viewers discuss issues related to on-screen representation, especially show cancellation.

This article takes Rebecca Wanzo’s assertion that “African American fans make hypervisible the ways in which fandom is expected or demanded of some disadvantaged groups as a show of economic force or ideological combat” and applies it to black viewers’ response to TV cancellations on Twitter. [1] Frequently deploying the language of mourning or utilizing existing hashtags concerned with diversity in Hollywood—like #RepresentationMatters—black viewers illustrate a deep investment in black shows. Though black viewers are not the only groups to use Twitter to save television series, many of the reasons viewers stated for the necessity or importance of black programs that appeared on the chopping block last year were rooted in raced considerations.

Cherry’s tweet (which has over 2,700 retweets and 4,000 likes) acts as a virtual funeral for the black shows cancelled in 2017. In the over 200 replies to Cherry’s tweet, several black twitter users add more television series to his list, share grief over unfinished story lines, relay their favorite moments, and argue about various causes for the cancellations. These replies include several critiques of the networks that cancelled the shows and bemoan the loss of characters that they believe portray black experiences with appropriate nuance. In a similar vein, Catherine Squire writing in the early 2000s noted,

“in providing a venue and support for alternative visions and critiques, Black-owned media can provide important loci for critiques of mainstream media and foster Black efforts to define and redefine Black images that circulate in wider public spheres” [2]

To be sure, this still holds true over fifteen years after the publication of Squire’s work, however, adoption of Twitter by black users, especially between the ages of 18-29, has helped migrate many of these discussions to the platform. This phenomenon provides further evidence for the designation of “Black Twitter” as a counterpublic space. [3] Black users’ engagement in Twitter discussions about the cancellation of a slate of black television shows illustrates both the creation and circulation of counterhegemonic discourses about television; specifically, that white television shows are not the only relatable narratives and that there is an audience for black cast dramas.

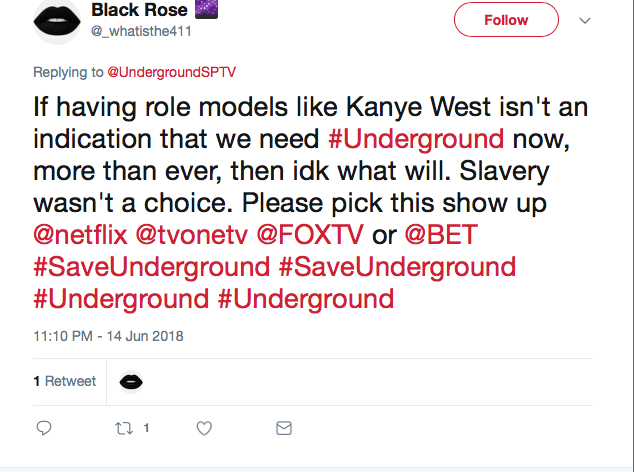

In addition to expressing grief, black viewers use Twitter to attempt to fight show cancellation; most notably through circulating petitions and collectively using hashtags like #SaveUnderground and #RenewPitch. The platform conventions and design of Twitter make black challenges to white helmed studios and networks more visible and easily identifiable. #SaveUnderground was started by John Legend (one of the executive producers of Underground) after Sinclair Broadcast Group bought out WGN America, the network that aired the series, and decided to scrap the entire network’s slate of original programming in favor of cheaper to produce procedurals. Fans of Underground quickly latched on to the hashtag and used other media like gifs and memes (which are easily integrated into tweets) to convey their disappointment with the news that the network was abandoning one of its most successful programs. In addition to using the hashtag, several fans created petitions and tweeted at several other outlets to pick up the show for its third season, including black owned networks like Oprah Winfrey’s OWN as well as streaming platforms Hulu and Netflix. The calls to #SaveUnderground or #RenewPitch were frequently paired with calls for greater diversity in Hollywood or emphasis that these stories were especially needed for the current times.

The discourses black Twitter users utilize to attempt to save shows from cancellation or to grieve the loss of black programming exude a palpable fear of losing the ground black viewers feel they have gained in the television landscape. This tangible fear is not without historical precedent. Much has been written about the “Golden Age of Television” ushered in by series like Mad Men and Breaking Bad, but recently many black viewers and critics believe that we are entering a Golden Age of Black TV. In an article for The Atlantic at the start of 2017, Angelica Jade Bastien declares that “2016 was a banner year for black people in front of and behind the camera” and credits showrunners Shonda Rhimes and Mara Brock Akil with opening the doors for a surge in black programming. [4] Notably, many of the series that were a part of the boom of black television in 2016 were dramas, some of which attempted to match the aesthetics of the white prestige cable dramas that had received much critical acclaim and cultural cachet. However, as Alfred L. Martin has argued, despite attempts, the “prestige” label seems to elude many black cast dramas. [5] The inability of many black cast dramas to secure the label of “prestige TV” and in some cases a lack of sufficient “crossover appeal,” — both, of course, rooted in raced, gendered, and classed structures of taste — likely heavily contributed to the cancellations of many black television shows in 2017. Addressing the sustainability of black television series, Bastien argues that this surge might potentially follow the boom and bust trend of black programming from the 1970s and 1990s. For the black Twitter users that expressed grief or dismay with huge losses to black programming in 2017, they likely remember the black television shows from the 1990s and early 2000s that swiftly disappeared after the end of United Paramount Network (UPN). Recalling the absence of programming that followed periods of relative abundance, black audiences are using Twitter to intervene in a repeated trend. Unlike the 1980s and late 2000s, black audiences have a direct way to demonstrate to networks that they have a deep investment in black programming and are willing to fight to see themselves represented on screen.

Relatedly, amidst news of black shows being cancelled, black audiences have also had to contend with the rise in reboots of classic white television series like Roseanne and Murphy Brown. Despite several sitcoms with predominately white casts returning to television, the trend of television reboots has elided black television sitcoms that were immensely popular in the 1990s. In fact, after Roseanne was cancelled following the star’s racist tweet about Obama White House senior advisor Valerie Jarrett, many black Twitter users took to the platform to ask why ABC would greenlight the television show of a known racist, while ignoring several popular black shows from the same era. Further, it is impossible to disentangle race from television reboots and the politics of nostalgia. While shows like Will & Grace and Full House enjoy a second run, black audiences are left asking why many of their classic shows aren’t even available on Netflix.

Recent scholarship in the field has looked at Twitter to research black audience reception. [6] However, to understand the range of black audience reception, research should extend beyond looking at live tweeting and second screen viewing to encompass the entire life course of black-oriented programming from the initial promotion of a series to news of its cancellation. Lastly, I return to Rebecca Wanzo’s assertion that black viewership has ideological stakes; mourning the loss of a show or fighting to save it are actions black audiences take to showcase their commitment to better representation on screen.

Image Credits:

1. Promotional Photo of Cancelled Series Survivor’s Remorse.

2. Tweet from Filmmaker Matthew A. Cherry

3. Tweet from Underground Fan

4. Tweet about the Necessity of Underground from Fan

Please feel free to comment.

- Wanzo, Rebecca. “African American Fandom and Other Strangers: New Genealogies of Fan Studies.” Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 20, 2015, n.p.” [↩]

- Squires, Catherine. “Black Audiences, Past and Present: Commonsense Media Critics and Activists.” Say It Loud! African-American Audiences, Media, and Identity, Edited by Robin R. Means Coleman, Routledge, 2002, pp. 45-76 [↩]

- See, Graham, Roderick and Smith, Shawn. “The Content of Our #Characters: Black Twitter as Counterpublic.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, vol. 2, no. 4, 2016, pp. 433-449 and Jackson, Sarah J. and Foucault Welles, Brooke. “#Ferguson is Everywhere: Initiators in Emerging Counterpublic Networks.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 19, no. 3, 2016, pp. 297-418.” [↩]

- Bastien, Angelica Jade. “Claiming the future of Black TV.” The Atlantic, 29, Jan. 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/01/claiming-the-future-of-black-tv/514562/. Accessed 16, June 2018” [↩]

- Martin, Alfred L. “Notes from Underground: WGN’s Black-Cast Quality TV Experiment.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 31, May 2018. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/notes-from-underground-wgns-black-cast-quality-tv-experiment/ . Accessed 16, June 2018. [↩]

- See, Chatman, Dayna. “Black Twitter and the Politics of Viewing Scandal.” Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World, edited by Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington, New York University Press, 2017, pp. 299-314. and Gonlin, Vanessa and Williams, Apryl. “I Got All My Sister with Me (On Black Twitter): Second Screenings of How To Get Away With Murder as a Discourse on Black Womanhood.” Information, Communication & Society, col. 20, no. 7, 2017, pp. 984-1004. ” [↩]

Thanks a lot. This have been more than important to me.