Comics ⟷ Media: What’s a Comic Book Fan Worth?

Benjamin Woo / Carleton University

In our age of massively marketed transmedial mega-franchises, fans are routinely portrayed as holders of uniquely valuable symbolic capital. Entertainment reporters cover the Comic Con beat and trawl social media for some indication of whether “the fans” will bestow their blessing on the latest round of blockbusters. As both reliable consumers and enthusiastic brand ambassadors, they are no longer poachers stealing textual pleasures out from under producers’ noses: they are the quarry.

Given the vital role intellectual property derived from comic books plays in Hollywood today, we might well expect their fans to be the most prized game of all. But, while superhero characters are more central to popular culture than perhaps ever before, comic books themselves and the practices that make up comic-book fandom clearly haven’t been mainstream for a long time. As a result, it is not clear how valuable comics fans actually are to the media conglomerates.

When I returned to reading periodical comic books after a long time as a trade-waiter, I was struck by the advertising, which is routinely cut from collected editions. There was so much of it and to so little purpose. I perceived a contradiction between how we talk about the value of fans and how companies talk to us through these promotional paratexts.

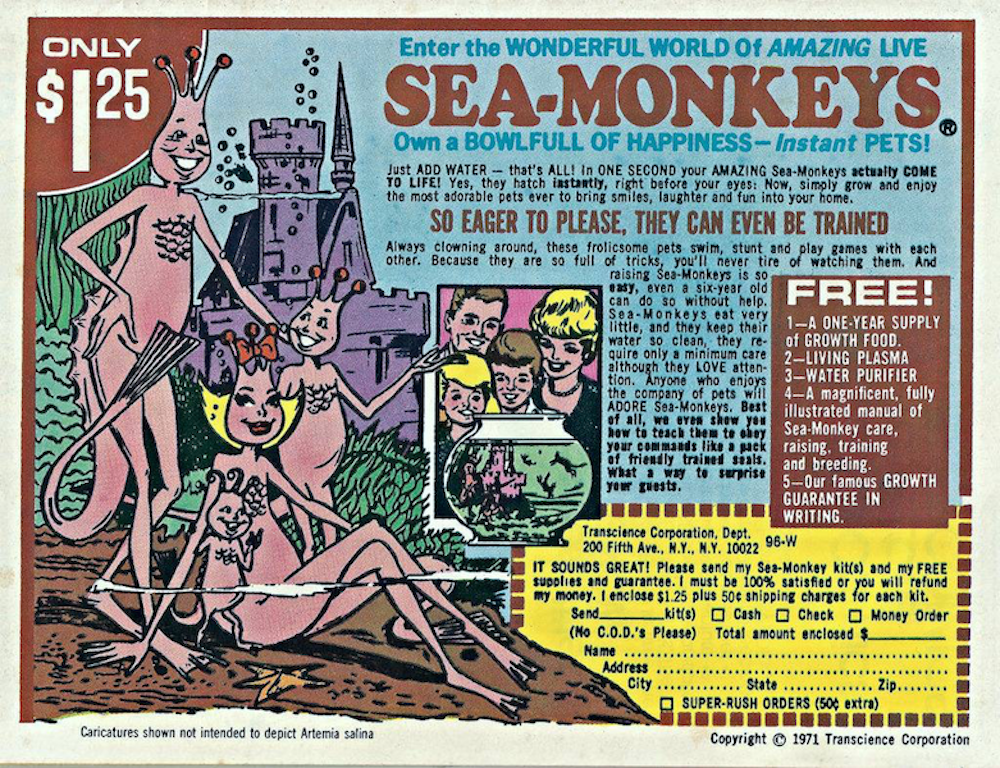

According to surveys conducted when comic books were still “new media,” virtually all children read comic books regularly. [1] Sales peaked in 1952, the year when American comic-book publishers sold a billion issues, [2] and we know anecdotally that a single copy would likely circulate among multiple young readers. This was all prior to marketers’ recognition of children’s influence on household product choices, and now-classic ads for Charles Atlas’s physical culture program, x-ray glasses, and the like point towards an understanding of comic book readers as a massive audience of children who were able to exercise some agency in the marketplace but had very little individual purchasing power—the perfect consumers, in other words, for a packet of freeze-dried brine shrimp and a cheap, plastic aquarium.

Compared with the children of the 1940s and ’50s, the average comic book reader of today is older and has more disposable income. Internal research on DC Comics buyers conducted in 2011 found most were white men between the ages of 25 and 44 who made an above-average income. This ought to be a highly desirable demographic, but an exploratory examination of the ads in one year’s worth of an ordinary DC Comics series suggests otherwise.

New Super-Man (re-titled New Super-Man and the Justice League of China with issue 20) was created and is written by the award-winning cartoonist, former Library of Congress Ambassador for Young People’s Literature and MacArthur “Genius,” Gene Luen Yang, who is best-known for the graphic novel American Born Chinese. The series stars Kong Kenan, a brash Shanghainese teenager who receives powers thanks to a qi-transplant from Superman. He and his compatriots in the Justice League of China eventually break with their government sponsors and strike out as independent heroes.

Although significant as an American comic series foregrounding Asian characters, New Super-Man is unremarkable in terms of sales. I just so happened to have a complete run to hand for this exercise. The January 2018 issue sold just over 10,000 copies to comic book stores according to John Jackson Miller’s monthly sales estimates at Comichron.com. Thirteen other DC series were in that ten to nineteen thousand sales band that month. I counted the pages of advertising, including “editorial” paratexts that were obviously promotional in nature, over the series’ most recent twelve issues (nos. 11–22):

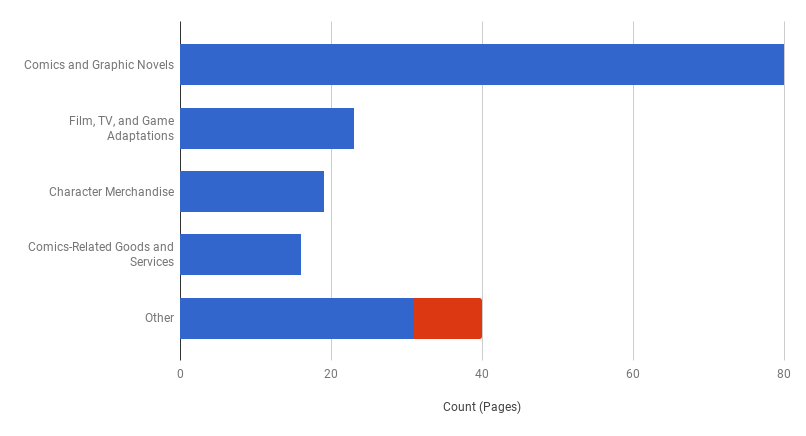

There were, in total, 178 pages of advertising, or slightly less than fifteen pages per issue. For context, a typical DC comic book costs US$3.99 (I pay about $6 in Canada after taxes) and contains a twenty-page story. As we can see, the single largest category is the eighty pages of advertising (just over six per issue, on average) devoted to promoting other comic books and graphic novels. Of course, this is almost exclusively for comics published by DC and its imprints—the one exception being an all-ages graphic novel from Scholastic.

Just under two pages in the average issue were used to advertise adaptations of DC Comics characters and properties in other media, including films like Justice League, video games like Injustice 2, and even novelizations of the CW television series The Flash and Supergirl. Slightly less space was devoted to selling character merchandise, including action figures and statuettes produced by DC Collectibles and t-shirts produced under licence by Graffiti Designs. Slightly less again promoted comics-related goods and services such as back-issue dealers, conventions, and the Kubert School; these ads typically use a comic book–inspired aesthetic, and several actually feature art of DC characters.

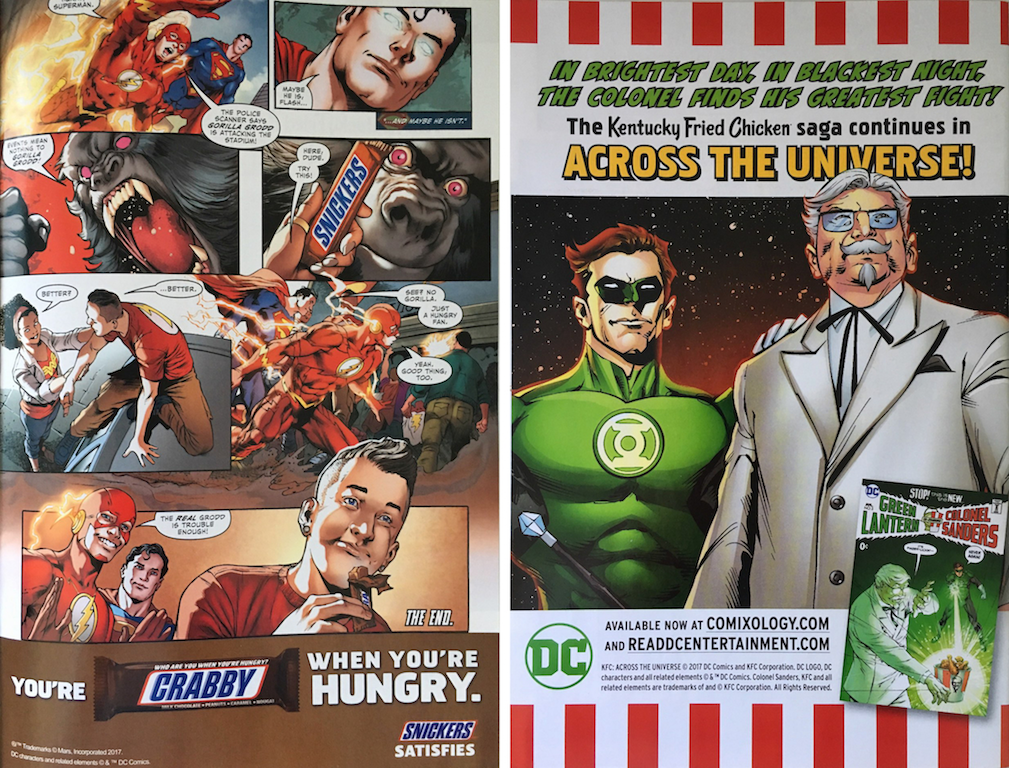

The second-largest category is a catch-all for “other” products, which comprised forty pages of advertising. Notably, most were for Warner Bros. media products, including TV networks and programs, films, and video games produced by other units within the Warners family. A further nine ads (in red in the figure above) had some kind of tie-in to DC Comics, such as a Snickers campaign featuring an apparent attack by the homicidal Gorilla Grodd that turns out to just be a hangry teenager or a curious Green Lantern / Colonel Sanders team-up comic. Across the twelve issues of New Super-Man / New Super-Man and the Justice League of China I examined, only a handful—a campaign for Steve Jackson Games’ Munchkin and a single page of advertising for Schick razors—weren’t to some extent in-house ads.

So, while comic book fans seem to be very useful subjects within the Warner Bros. entertainment conglomerate in much the way Eileen Meehan argued Star Trek fans served as backstop consumers for Paramount, DC does not seem able to convince advertisers of their value. [3] Of course, advertising is in crisis across virtually all media, but it is nonetheless striking that comic book fans, constructed by so much industry discourse as the ideal consumer of convergence culture, garner so little attention from major retailers, car companies, telecommunications providers, and other top advertisers. While much more research is obviously needed on the financial arrangements that result in this situation, it seems to lend credence to the hypothesis that comic book publishers are principally “licence farms” for transmedia IP. [4] The comic books themselves are, at the level of corporate strategy, almost an afterthought, and their readers are worth about $3.99.

As this is my final column for Flow this year, I want to take a moment to thank the editors for the invitation to contribute. I’ve really appreciated the opportunity to bring comics studies and media studies into dialogue in this venue. In particular, Maggie Steinhauer has been helpful throughout the process, sending me due-date reminders, catching embarrassing typos, and running down alternate sources for images when they disappeared from the web. 🙏

Image Credits:

1. Amazing Live Sea-Monkeys (Caricatures Shown Not Intended to Depict Artemia Salina),”

2. Bernard Chang variant cover to New Super-Man 19 © 2018 DC Comics

3. Advertisements in New Super-Man / New Super-Man and the Justice League of China, nos. 11–22, coded by the author (don’t @ me) (author’s screen grab)

4. Ads for Snickers (left) and Kentucky Fried Chicken (right) featuring DC Comics promotional tie-ins scanned by the author (scan from author’s collection)

Please feel free to comment.

- Zorbaugh, Harvey. 1944. “The Comics—There They Stand!” Journal of Educational Sociology 18: 197-98. [↩]

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. 2010. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Translated by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. [↩]

- Meehan, Eileen R. 2000. “Leisure or Labor?: Fan Ethnography and Political Economy.” In Consuming Audiences? Production and Reception in Media Research, edited by Ingunn Hagen and Janet Wasko, 71–92. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. [↩]

- Rogers, Mark C. 1999. “Licensing Farming and the American Comic Book Industry.” International Journal of Comic Art 1 (2): 132–42. [↩]

As a regular comic book reader myself, I am explicitly aware of the languishing comic book fandom nowadays. I remember reading Manga as my regular recreation when I was in my middle school, and I has a monthly routine to follow one of a comic magazine in China which is the only agency back then to have the copyright of my favorite Manga. But as the digital revolution taking place, my peers and I find reading Manga a time-consuming activity, while there are better way to entertain ourselves, so the animation gradually has more influence on the teens. The magazine stoped publication for over 5 years now. I think the relation of Manga and its adaptations for animation is very similar to the relation of comic books in American popular culture and superhero characters in visual media including animation and movies. The latter is derived from the former, but eventually outdone the value of its originals. I think the reason is primarily due to the nature of the medium, while the digital and forms are more acceptable than the physical forms.