Comics ⟷ Media: Bam! Pow! Comics Aren’t Just for White Men Anymore!

Benjamin Woo / Carleton University

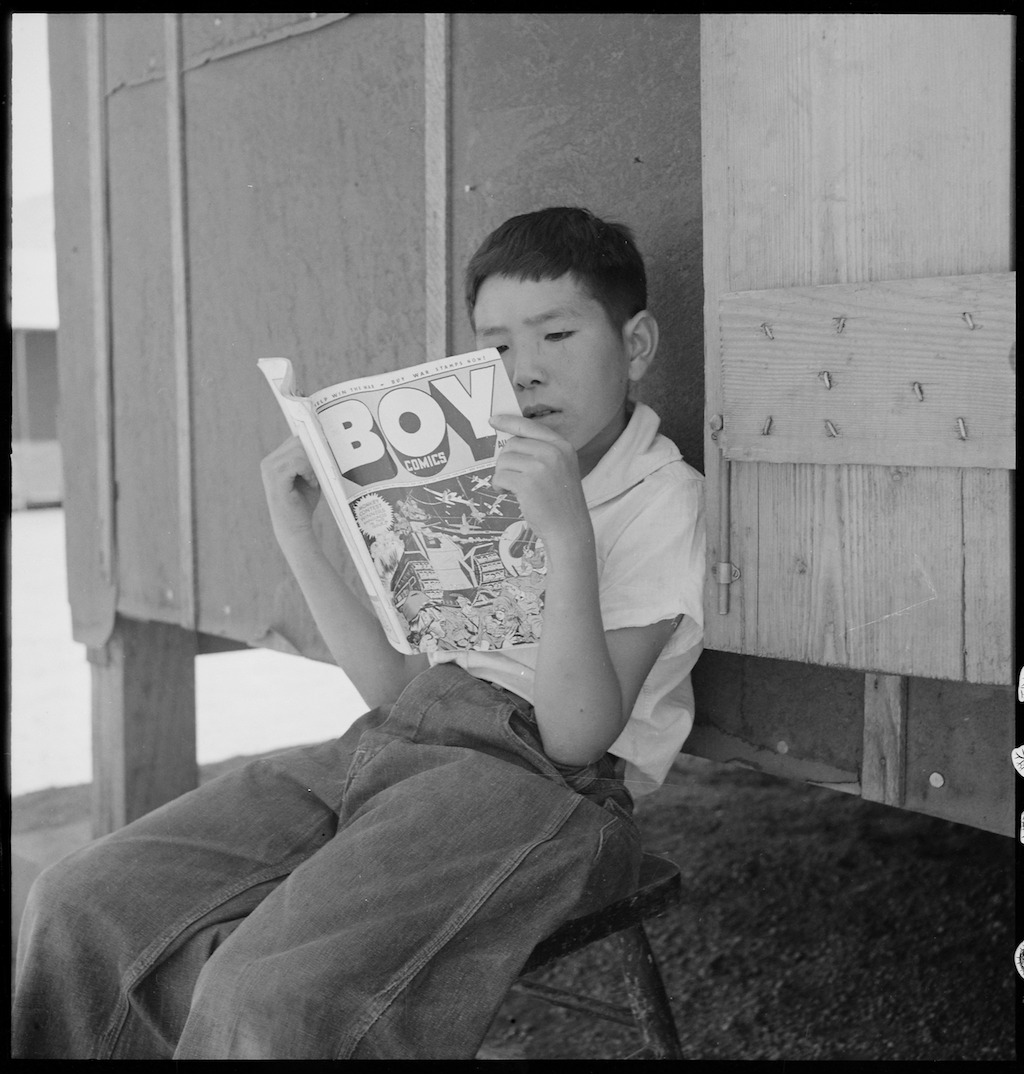

In 1942, the War Relocation Authority hired photographer Dorothea Lange to document the internment process following Executive Order 9066. Lange took this picture at the concentration camp in Manzanar, California, where roughly ten thousand Americans of Japanese ancestry – including a hundred orphans in the “Children’s Village” – were imprisoned. It and all the rest of Lange’s pictures were suppressed during the war. They remained largely forgotten in the National Archives for some time afterwards; some have suggested that her camera was too sympathetic or that she showed too much of the conditions in the camps – despite not being allowed to shoot the fences, watchtowers, or soldiers that presided over the camp.

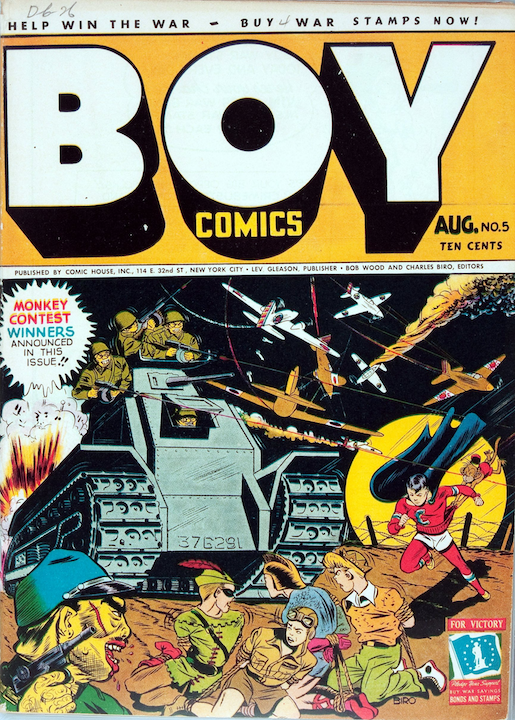

Lange originally captioned the image, “Evacuee boy at this War Relocation Authority center reading the Funnies.” There’s enough polite euphemism here that I feel a little odd pointing out that he’s not actually reading the “funnies” – that is, newspaper comic strips – he’s reading a comic book. More specifically, Boy Comics #5, which was published by Lev Gleason’s Comic House in August 1942.[1] In the photograph, you can make out the shape of a tank and airplanes, signalling that it’s (at least in part) a war comic. The comic is as larded with jingoistic messages as you would expect: several stories pit their plucky young heroes against Nazis and their fifth-column supporters; exhortations to buy war bonds appear throughout; and one of the mottoes printed at the bottom of the page reads, “If you’re a red-blooded American boy—read Boy Comics!” But the black and white image simply doesn’t do it justice. Here it is in colour.

When I look at Lange’s photograph, I can’t help trying detect some trace of this red-blooded American boy’s response: What did he make of the Little Wise Guys accusing the local butcher of sheltering a “Jap”? How did he feel seeing the likes of Crimebuster, Young Robinhood [sic], Bombshell, and Swoop Storm menaced by buck-toothed, Day-Glo monsters that were supposed to somehow represent him? How did the comic’s celebrations of (white) American boys’ bravery, cleverness, and decency look from inside a prison camp where he was being held for no other crime than his Japanese ethnicity?

I’ve been thinking of this photograph a lot in recent weeks as the field of American comic books appears to have, once again, reached a boiling point around diversity and “identity politics.” Men who call themselves comic book fans and “comic book skeptics” have taken to Twitter and YouTube to complain about changes in superhero comic book publishing that temporarily placed different kinds of bodies in the costumes of characters like Spider-Man, Thor, and Wolverine, and about new series like The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl and Ms. Marvel that seem intended to appeal to … someone different from them. They cheered when a Marvel executive blamed diversity initiatives for declining sales (an interpretation that has been disputed within the comics press and the mainstream media) and when every one of their GLAAD-nominated titles had been cancelled. The watchword is “forced diversity”: They’re not opposed to women, people of colour, or LGBTQ characters, they just don’t want them shoehorned into perfectly good books with perfectly good stories for “political” rather than narrative reasons.[2]

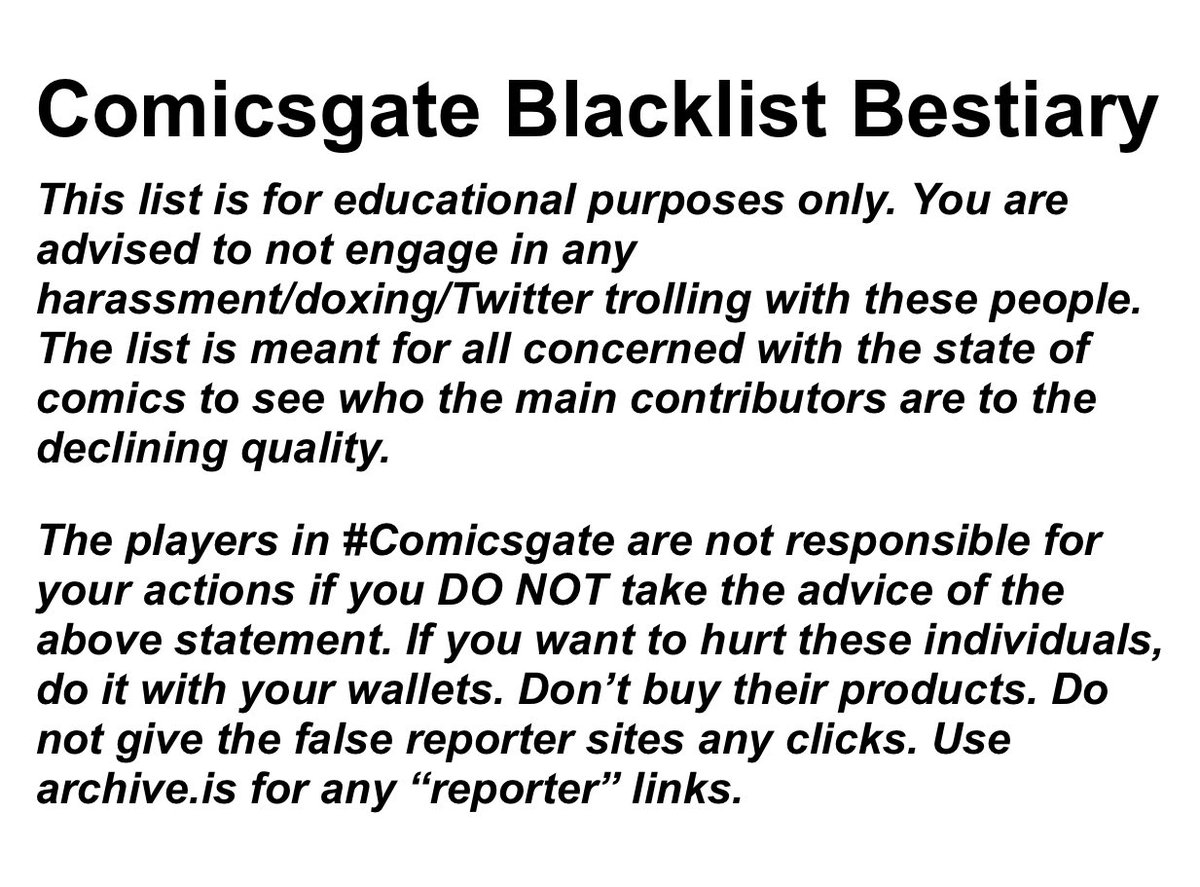

This is another instance where we need to see “comics” as part of the broader media culture, rather than a corpus of texts defined by the specific properties of their cultural form, and as part of society, rather than subculture insulated from social and political currents. Indeed, at least some participants have explicitly modelled themselves on the Gamergate movement. When it was still white hot, there were already calls for a parallel “Comicsgate” to take comic books back from the social justice warriors. It didn’t quite take off at the time, but that name has begun to recirculate. On the one hand, the moniker seems apt, as the lists of women, people of colour, and self-described liberals described as “contributing to the declining quality” of the comic book industry have been posted online – always with the proviso that this is definitely not a call to harass them. On the other hand, as Inverse’s Eric Francisco points out in a Comicsgate backgrounder, they lack a specific “ethical controversy” to provide the post hoc motivation for their campaign: they “seems to just want less diversity, both in characters and creators, in an attempt to save comics and keep the medium white, male, and familiar. That’s it.”

In my latest book, Getting a Life: The Social Worlds of Geek Culture, I discuss how widely circulating discourses about authorship, gender, and play contribute to the embrace of what Michael Kimmel calls “aggrieved entitlement” within some corners of geek culture. These discourses are not inherently toxic, but they have shaped the emotional texture of this specific politics of white masculinity:

- First, many of the fan communities composing geek culture remain highly invested in particular conceptions of authorship. They are, in Herbert J. Gans’s terms, a creator-oriented public of popular culture. Interviewees frequently deployed ways of thinking and speaking that identify with authors, and the confidence with which the Comicsgaters deputize themselves to police the meaning of characters and who they’re for relates to this creator-orientation.

- Second, I found a lot of gender talk. Some of it was of the “fake geek girl” variety, but more of it focused on stereotypes about “nagging” wives and girlfriends. Many men spoke specifically of the women in their lives forcing them to get rid of collections and spend less time engaged in their hobbies. In this way, women were discursively constructed as a constraint on their free time.

- Third, the wide-ranging use of irony and play obfuscates the intent and effects of speech acts. Moreover, the playful “troll mask” serves to insulate their self-concept by placing these activities within a “magic circle” separate from their “real” lives and selves.

In the last year or so, Gamergate and other troubles within geek culture have been seen as an early warning – missed by too many of us – of the rise of the authoritarian alt-right in the United States and other western nations. Comparing the nascent Comicsgate community with its analogues in other fields is an opportunity to investigate what conditions determine how these controversies work themselves out. Without minimizing the harms experienced by specific targeted creators and critics, why hasn’t the comics version taken off to the same degree as Gamergate, yet refuses to burn out? Might it be, for instance, related to the demographic composition of the comics workforce? Or to the way that publishers are caught in between a business model that privileges graphic novels and trade paperbacks that circulate in trade bookstores and libraries and one that remains tethered to the “floppy” periodical format and its basically subcultural audience?

Let’s be crystal clear. Harassment and bullying are wrong. Racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia are wrong. I’m not trying to empathize with the Skeptics. My attempts to understand them are more selfish – as Pierre Bourdieu was fond of saying, “sociology is a martial art, a means of self-defense.” But, importantly, they’re not only wrong but also incorrect. In a paper delivered at this year’s International Comic Arts Forum, Aaron Kashtan pointed to the “direct-market centrism” that blinds the Injustice League to the full breadth of what’s happening in comics today. And of course any media critic worth their salt knows that culture and politics are always intertwined. That boy in Manzanar certainly didn’t have the luxury of believing comic books didn’t have an agenda.

Image Credits:

1. Reading the Funnies, Dorothea Lange

2. Cover, Boy Comics #5, by Charles Biro

3. Preamble to the Comicsgate Blacklist Bestiary

Please feel free to comment.

- You can read the whole thing at the Digital Comics Museum. [↩]

- For an account of these events from their point-of-view, see Encyclopedia Dramatica’s ComicGate entry. Note how the site’s hedging as “parody” and “satire” provides cover for its aggressive framings of these events and the people involved. [↩]

We all know how to get the chrome browser online.

Now we are all knowing about this game here.