Friction Points in Influencer Marketing

Cynthia Meyers / College of Mount Saint Vincent

Recently the YouTube star Logan Paul’s vlog featured a dead body; in the resulting public outrage Paul (15 million YouTube followers) lost some lucrative advertising and production deals. Last year anti-Semitic jokes similarly affected YouTube star PewDiePie (59 million followers). Logan Paul and PewDiePie are two of the most successful “influencers,” social media stars who are paid to promote brands to their fans. Fearing that traditional celebrities who endorse products may be dismissed as “inherently inauthentic,” advertisers have turned to these influencers instead. Their seeming authenticity is, as Faris Yakob points out, “predicated on the idea that what they are saying is something they believe, an expression of who they are, because that’s what we want to imitate.” The public outrage they excite, which might seem to pose a risk to advertisers, is in fact a feature, not a bug: such outrage is more likely to cement these YouTubers’ bonds with young fans than to weaken them. This is one of many ways in which the new “influencer” system departs from traditional advertising. A few of the resulting issues or “friction points,” in industry jargon, are the subject of this article.

Influencers provide content that attracts audience attention, which they sell directly to advertisers, without involving the media companies such as networks that once mediated such transactions. To find and manage influencers, advertisers have turned instead to new agencies and platforms that are springing up for the purpose (Famebit, Niche, Collective Bias, Revfluence). Some allow would-be influencers to seek brand deals through automated platforms. The evolution of these new supply chains of audience attention is difficult to predict: many assume a shake-out looms, and though it seems likely that such matters as pay rates and content control decisions will become more standardized, it remains to be seen to what extent such standardization is possible or desirable in a system which invented itself in conscious opposition to the advertising conventions of the past.

Traditionally, in most culture industries, a talented few at the top of the pyramid get almost all the money and fame. In the influencer industry, however, some advertisers have turned away from those with vast followings and are instead cultivating “microinfluencers” (with 10,000 to 100,000 followers) whom they believe more credible and relatable. The “friction point” for brands, however, is having to manage hundreds of “brand ambassadors” instead of one celebrity endorser or one ad agency. Many brands cycle through hundreds of microinfluencers, who must themselves must constantly contract with new brands for new deals (Juliette Borghesan, personal interview, Dec. 14, 2016). Is this churn a transitional phase in influencer marketing or a sign of structural precarity?

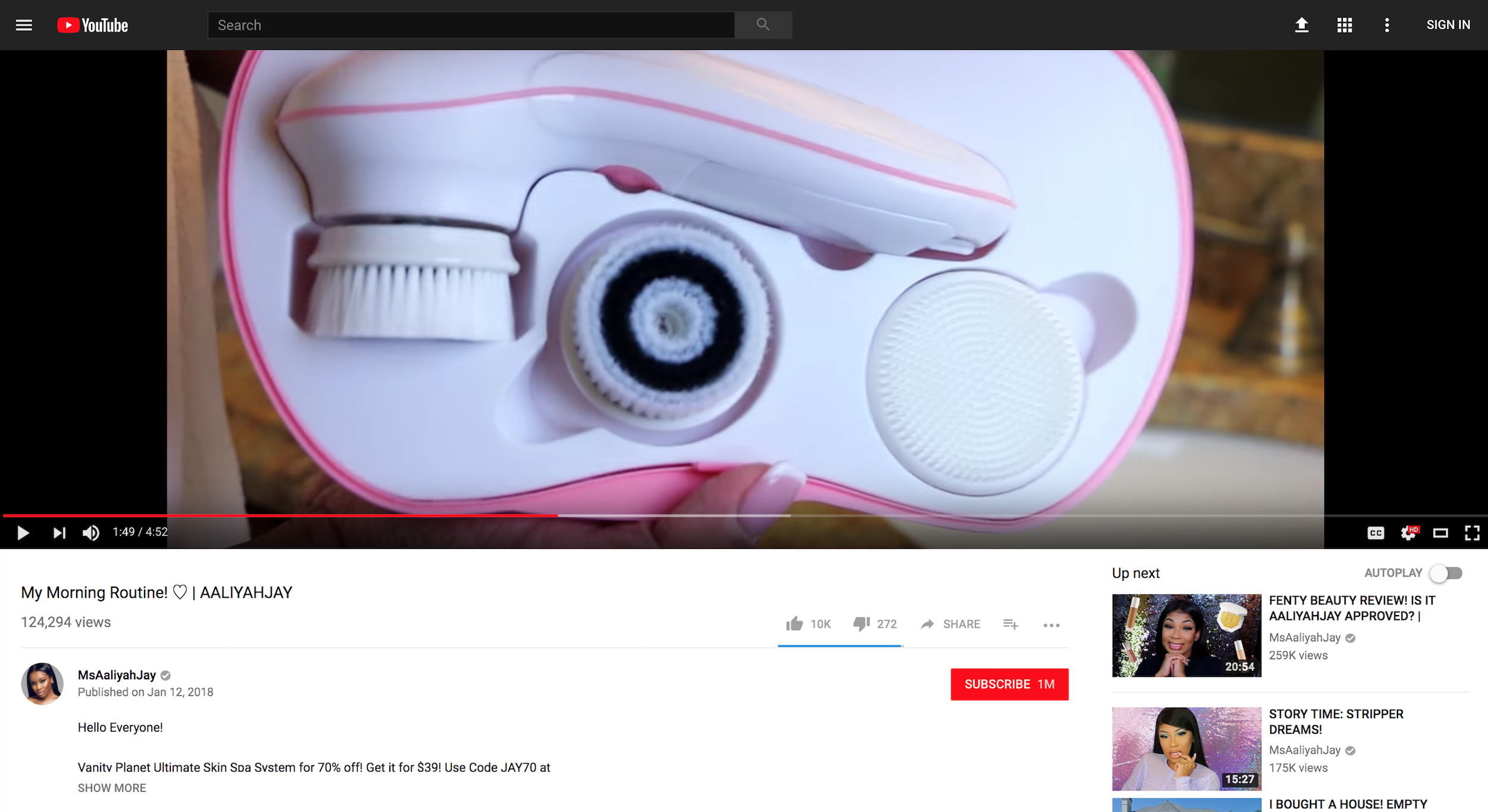

Media metrics for negotiating the price of media time and space, such as audience size and demographics, are not clearly settled for the influencer market. Brands, of course, want proof of “return on investment” (ROI). Initially brands evaluated the effectiveness of influencers by measuring numbers of followers, clicks, likes, shares, and other easily gathered data. But inflated metrics, fake influencers, and bots undermined the trustworthiness of such data. Furthermore, advertisers in this new market seek not just exposure but “engagement,” which is even harder to define or measure. Influencers, advertisers assume, can provide this engagement because of their intense parasocial bonds with their fans, who see them as peers speaking the truth about products. Some advertisers provide promotional codes to influencers so that when their fans purchase with the code, they can measure sales and calculate influencer commissions.

Accountability, that is, who is responsible for the brand message in the content, is another major “friction point.” Ad agencies had always been accountable to clients for aligning advertising with the brand’s image. The first loyalty of influencers, however, is to their own content “brand” because that is what attracts their fans. They must be careful to integrate the product in an “organic” way within their own content—in, for example, their tips on cosmetics, fashion, healthy living, cooking, or athletic achievement. The amount of content control exercised by the brand depends on both the brand and the influencer. Certain brands, such as Coca-Cola, send specific instructions to influencers (Borghesan); others are entirely hands off. Some influencers, such as Casey Neistat, insist that they must have complete content control when integrating brands; others, especially microinfluencers, simply post what is sent them by the brand. On the one hand, advertisers want to control their brand image; on the other, influencers want to seem independent and authentic, and, in fact, must succeed in this if they are to sell products. The matter is further complicated by the blurring of the once-sharp line between content and ad. While both brands and influencers assume they have much to gain by such blurring, they also have much at risk—control on the one side, credibility on the other.

Both brands and influencers have a motive to hide their transactional relationship from consumers. In the 1920s the Federal Trade Commission cracked down on advertising “testimonials” for deceptiveness when an endorser did not actually use the product. Likewise, recently the FTC has been issuing guidelines that paid social media posts be tagged or labeled as ads. Yet brands employ influencers to circumvent audiences’ avoidance of traditional advertising; labeling an influencer’s content as “ad” may undermine that goal. Viewers who skip a Taco Bell commercial may happily watch Tyler Oakley vlogging about eating a Taco Bell product, so long as it’s not labeled a Taco Bell commercial. And yet many fans value the influencer precisely because she is earning revenue from brands. As one Jake Paul fan explained, “He makes a lot of money off YouTube!” For those fans, their influencers model an aspirational vision of a life of creativity, passion, and wealth, of which extensive product consumption is a necessary and desirable part.

To reduce their dependence on advertisers, some influencers have developed their own “merch”: t-shirts, shoes, athletic wear, cosmetics, jewelry, nutritional supplements and other products made cheaply and sold for a high price resulting from artificial scarcity and exclusivity. The influencer’s pop-up shop or one-time online “drop” may be a fan’s only opportunity to buy this merch. Some influencers, then, are not only disintermediating the media business by being their own content producers, distributors, and media agencies, but are also exploiting direct-to-consumer retail strategies to distintermediate traditional retailers. If advertisers are driven off by daring, “authentic” content, these merch empires provide a good hedge for influencers.

Advertisers have always searched for ways to overcome consumer cynicism. In the 1920s and 1930s, they cultivated “sincerity” to convince cynical consumers that their ads were not like fraudulent patent medicine ads. In the 1960s, the Creative Revolution’s emotional appeals, humor, and irony grew up in contrast to the dubiously factual “hard sell” of which consumers had grown suspicious. Today, when audiences can avoid altogether the traditional ads they suspect, the simplest solution for advertisers seems to be integrating their brands into the most authentic-seeming content, content that looks user-generated. The YouTube aesthetics of shaky hand-held camera work, jump cuts, and bad shot compositions signal authenticity. If the definition of “content” is what audiences want to see and “advertising” is what brands want audiences to see, then influencer content seems to marry these categories. The marriage may not last. Audiences may become jaded by the constant pitching and promoting, and brands may come to doubt the efficacy of influencers. At present, however, it seems to be working beautifully. Audiences may be revising their definition of “content” so as to expect it to include advertising: as one observer notes, “entertainment for adolescents currently consists of unvarnished requests for money and devotion.” We may in fact be returning to the type of branded sponsored content common from the 1930s through the 1950s, when audiences eagerly tuned in to watch Arthur Godfrey sip and joke about Lipton Soup.

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screen grab

2. Author’s screen grab

3. Author’s screen grab

4. Tyler Oakley: “My First Cool Ranch Doritos Locos Taco”

5. Author’s screen grab

6. Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts Lipton Commercial

Please feel free to comment.

So this is a useful way to make movies in windows.