Saving New Sounds: Podcasts and Preservation

Jeremy Wade Morris / University of Wisconsin-Madison

We are, as commentators have noted, in the midst of a “Golden Age of Podcasts”; a moment where the choice for quality digital audio abounds, and where new voices and listeners connect daily through earbuds, car stereos, home speakers or office computers. Depending on how you define it, podcasting is either just over 10 years old, more than 20 years old, or merely the latest soundwave in radio’s much longer history. [1] However you date it, in the decade since 2004 when the term “podcasting” was inadvertently coined the format has exploded: there are now over 300,000 podcasts and 8 million episodes in over 100 languages, with new ones launching every day. [2]

Given how ubiquitous and available podcasts are, you might assume they would not face the same preservation risks as, say, old radio tape reels, transcription discs or celluloid film stock. Podcasts are largely free and their near-instant availability on multiple devices makes them seem as if they are in endless supply. They take up relatively few megabytes, which makes it easy to store a lot of them, and they are often available through multiple channels and aggregators (iTunes, Stitcher, SoundCloud, etc.).

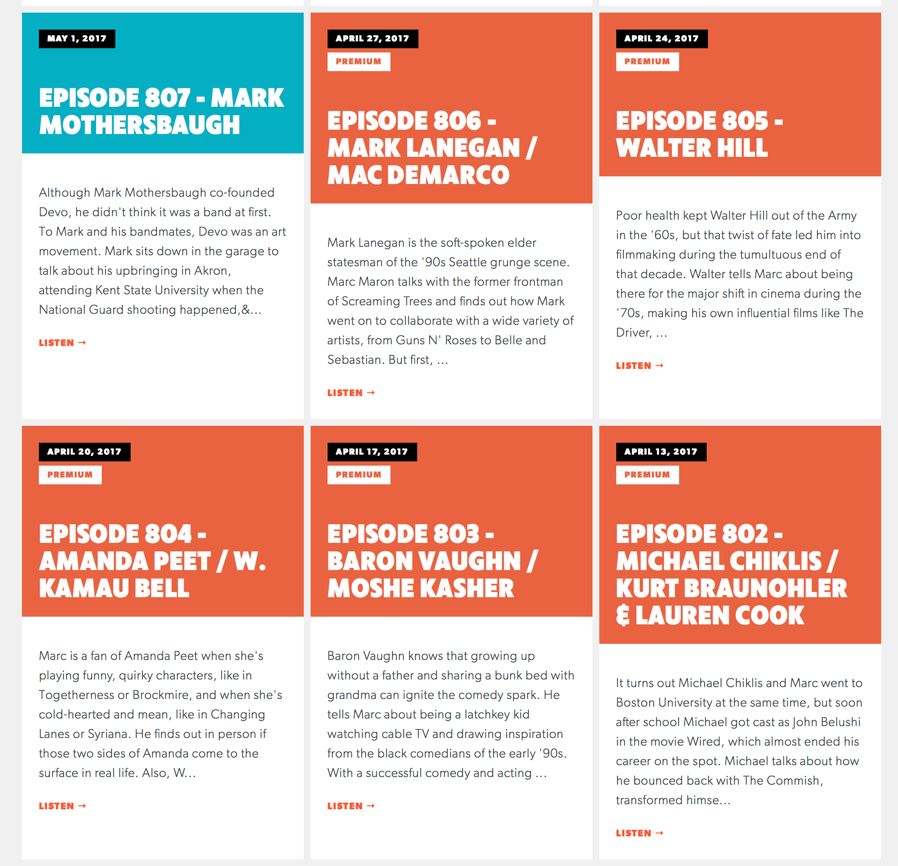

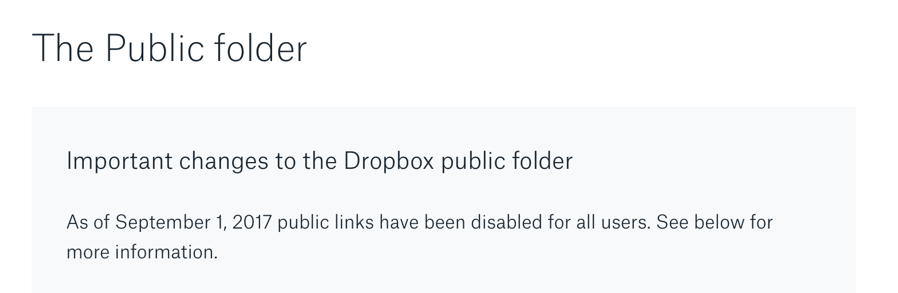

But podcasts are surprisingly vulnerable; podcast feeds end abruptly, cease to be maintained, or become housed in proprietary databases, like iTunes, which are difficult to search with any rigor. Many podcasts get put behind paywalls as they get popular, or as back catalogues become a potential source of revenue. Then there’s the precarity of the very platforms that help make up podcasting’s diffuse and sometimes DIY infrastructure: I recently heard from an independent podcaster who had been hosting their show via the file management app/website Dropbox, but once that company made significant changes to its “public folder” feature, the podcaster was left scrambling to find another solution for where to host their files (and had to return to older shows to update the URLs and locations of new files).

It’s not just under-resourced independent podcasters whose files are at risk though. Well-known Internet entrepreneur and former MTV VJ Adam Curry shares a similar story. In 2014, he sent out a tweet asking his 40,000+ followers a relatively straightforward question: “Looking for a full archive of Daily Source Code mp3s.” The podcast he was trying to track down, the Daily Source Code, was an early (2004), and relatively popular podcast, that helped shaped the emerging format. It was an odd request, in some ways, since Curry was the creator, host and producer of the Daily Source Code (which ran from 2004-2013 and over 860 episodes). It’s not entirely clear what happened to Curry’s original copies of the shows; but it’s clear he doesn’t have them: “For a number of [stupid and careless] reasons, I am not in possession of most of these.” [3] If the very people producing these new artifacts of audio culture aren’t necessarily saving their work, who is?

Of course, we can’t fault Curry for not saving the shows. If you’ve ever produced a podcast, you know that just getting the audio up and running, day after day, week after week, is accomplishment enough. There are countless hosts, producers and engineers without the foresight, budgets or means to label, store and archive their audio. Also, because of the mundane nature of a lot of podcasts, many podcasters probably do not realize the audio they are making is shaping the early stages of this emerging format, and doing so in a way that media historians, scholars and hobbyists might later want to analyze, research, teach and reference.

Unfortunately, we know this from precedent. Much of radio’s history has been lost to vagaries of time and only now are we starting to make sense of what we’re missing. The Radio Preservation Taskforce, for example, is working hard to try and preserve what remains of radio’s past, but claims that close to 75% of historical radio recordings in the U.S. have already been lost, destroyed, or are otherwise inaudible. The numbers are similar, if not worse, for silent films.

Podcasts might be newer than pre-1975 radio, and more digital and accessible than silent films, but this alone doesn’t ensure their continued existence. We are deep enough into our experiences with technologies like the world wide web, spinning disc hard drives, and error 404s to know that digital objects bring new challenges for saving, locating and retrieving data over time. [4] Thankfully, sites like The Internet Archive are addressing some of these challenges, and providing new tools for thinking through, and doing, digital histories. The Internet Archive also has a growing audio database, part of which is devoted to podcasts. There are also a number of libraries that are beginning to bolster their digital audio collections and to take podcasts seriously as a format that deserves attention and long-term stewardship.

For the last few years, I’ve been coordinating a revolving team of students, technicians and faculty (primarily Dr. Eric Hoyt), in order to build a site to preserve podcasts and make them more researchable for audio scholars and enthusiasts. You can try out the beta version of PodcastRE (short for Podcast Research) to search for keywords and metadata associated with the 240,000+ audio files and over 1300 podcast feeds. There are also several thousand interactive transcripts (thanks to the good folks at AudioSearch). It’s far from comprehensive, but it’s growing daily and it will, when it’s complete, make podcasts and other born-digital audio as easy to use and research as textual resources you’d find in a library. It’ll also create a repository for these often vulnerable and ephemeral media texts.

Ultimately, we hope the database will allow media and sound researchers to ask questions about podcasts and podcasting: how do podcasts differ, sonically and aesthetically, from radio? What new voices and perspectives do podcasts make audible and which ones do they silence? In what ways are the traditional conventions of the broadcasting industry shaping this new outlet? How are producers and consumers reimagining the broadcasting in light of podcasts? But we’re also hoping researchers from a broad array of disciplines and fields will be able to use podcasts and audio as resources to address a wide range of humanistic and scientific questions.

Whether we’re in some new golden age of audio, or whether we’re just hearing the vibrations of radio reformatted, we can at least hopefully agree that podcasting is a vibrant and growing space for new kinds of listening publics. [5] If so, you’d think we’d have a more comprehensive strategy for saving these new sounds than optimistically assuming podcast producers are keeping proper backup copies of their shows, or that platforms like Dropbox, iTunes or SoundCloud will continue to provide the same kinds of services for the foreseeable future.

By virtue of the fact they are taking part in a format’s infancy, today’s podcasters are making history by default. What today’s podcasters are producing will have value in the future, if not for its content, but for it tells us about radio and audio’s longer history, about who has the right to communicate and by what means. [6] If we’re not making efforts to preserve podcasts now, we’ll likely find ourselves in the same sonic conundrum many radio historians now find themselves in: writing, researching and thinking about a past they can’t fully hear.

Luckily for Curry, shortly after his tweet for help, he discovered that a “super friend of the show” had a copy of the entire Daily Source Code archive and was uploading it and making to available to fans through Bit Torrent Sync. As with much of what we have left of radio’s golden age, fans and enthusiasts were helping rebuild the missing archive. As a result, one of podcasting’s first big shows wasn’t lost to time. The same can’t be said for many other feeds that have already disappeared and the many more that might if we don’t make preserving podcasts a priority.

Image Credits:

1. Golden Age of Podcasts for Everyone!

2. Author screenshot of the premium paywall for the WTF with Marc Maron podcast.(author’s screen grab)

3. Author screenshot of a contingent platform, from a Dropbox press release. (author’s screen grab)

4. Author screenshot of a tweet by Adam Curry looking for archives of his own show. (author’s screen grab)

5. Author screenshot of http://podcastre.org, the beta version of the database we are building to help preserve podcasts and make them more useable for researchers. (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Bottomley, Andrew J. (2016) “Internet Radio: A History of a Medium in Transition.” [Dissertation] Order No. 10154207. The University of Wisconsin – Madison. ProQuest Dissertations. [↩]

- Hammersley, Ben. (2004, February 12). “Audible Revolution.” The Guardian. Section T1. Accessed July 13, 2007 http://www.theguardian.com/media/2004/feb/12/broadcasting.digitalmedia. [↩]

- Curry, Adam (2014, January). “The Daily Source Code Archive Project: Bringing The DSC Back”. [blog] Accessed October 22, 2016 http://blog.curry.com/2014/01/15/theDailySourceCodeArchiveProject.html [↩]

- Brügger, Neils (ed.). 2010. Web History. New York: Peter Lang [↩]

- Berry, Richard. 2016. “Podcasting: Considering the evolution of the medium and its association with the word ‘radio’.” Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media 14 (1):7-22. doi: 10.1386/rjao.14.1.7_1.; Hilmes, Michele. 2013. “The New Materiality of Radio: Sound on Screens.” In Radio’s New Wave: Global Sound in the Digital Era, edited by Jason Loviglio and Michele Hilmes, 43-61. New York: Routledge.; Lacey, Kate. 2013. Listening Publics : The Politics And Experience Of Listening In The Media Age. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press. [↩]

- Sterne, Jonathan, Jeremy Wade Morris, Michael Baker, and Ariana Moscote Freire. 2008. “The Politics of Podcasting.” Fibreculture (13). Available at http://thirteen.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-087-the-politics-of-podcasting/ [↩]

This publication is interesting.