Live Piracy: New/Old Directions in TV Flow

Evan Elkins / Colorado State University

Most people probably experience TV piracy as a time-shifted practice. [1] That is to say, it either involves leaks of TV episodes ahead of their official airing or, more likely, after-the-fact viewing via familiar methods: file-sharing, illegal streaming, password-sharing and even the extant practice of trading “physical” media like DVDs. This temporal relationship can vary, but most forms of unauthorized media consumption generally exist out of sync with scheduled television broadcasts.

But as internet speeds have grown faster and streaming technologies have become increasingly sophisticated, unauthorized online livestreams have gained prominence as a way for viewers to enjoy television programs and events as they air. Live piracy asks us to consider several issues: the continued importance of live television in a supposed era of time-shifting and a la carte delivery, the oft-ignored relationship between liveness and media piracy, the labor involved in creating and finding illegal livestreams, and the potential impacts of these practices on legacy media institutions. Indeed, while many have suggested that live broadcasts (sports, usually) represent the final tether keeping TV viewers from cutting the cord, liveness no longer seems to be the exclusive property of the major broadcasters—if it ever was.

Pirate Portals

Pirate livestreaming represents an uneasy mixture of residual, dominant, and emergent television technologies and cultures. This is apparent not only in the experience of watching traditionally live television through unauthorized digital means, but also in the ways livestream services present their offerings to the viewer. Take the many link-aggregation sites that provide unauthorized streams of sporting events, award shows, and other programs sourced from decrypted satellite signals, adapters that enable online transmission of TV feeds, and repurposed feeds of official services like MLB.tv, NBA League Pass, or Sky Go. At first glance, many of these sites look and operate like the curatorial VOD platforms that Amanda Lotz calls “portals”—services like Netflix, HBO Now, Hulu, and CBS All Access. [2] Like portals, unauthorized livestreaming services present a series of intentionally selected programs and streams to viewers. However, the curation process on these services is more contingent—informed by what illegal streams are made available through the elusive informal economies of unauthorized TV distribution and exhibition.

As Lotz argues, portals are distinct from TV channels in part because of their emphasis on curation over scheduling. So, while pirated livestreams do indeed recall portals in their range of selection, they also resemble TV Guide listings or digital cable menus in their invocations of individual television channels as well as their chronological listing of programs on offer. In other words, if a VOD platform like Netflix incorporates TV programming from various channels and locales under the Netflix brand and promotes the experience of watching whatever you want whenever you want, pirated livestreaming brings to mind the more traditional TV experience of tuning into a particular channel at a specific moment in order to watch something that’s happening right now.

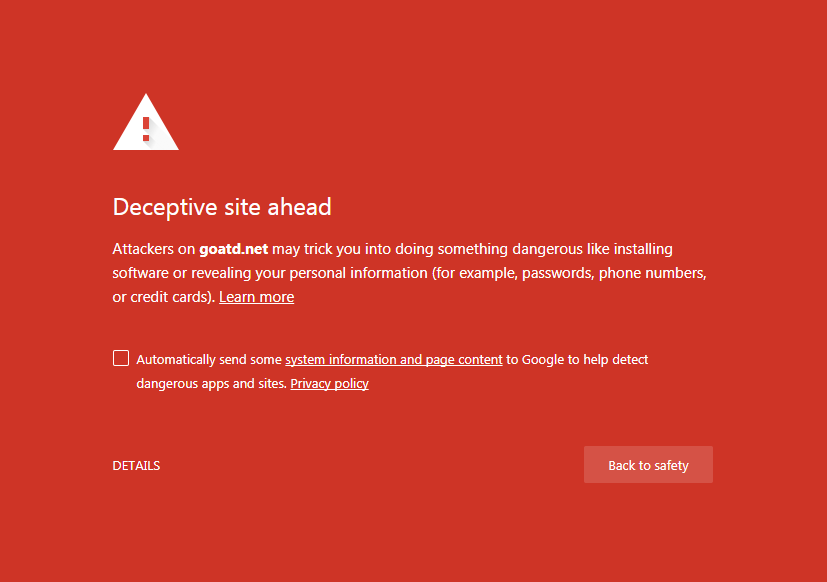

As with many forms of unauthorized media, watching a pirated livestream is a practice marked by hiccups, failures, and interruptions. Pop-up ads, in-browser malware warnings, and variable video quality all reveal the absence of the slick, expensive infrastructures that bring HD images to us via (relatively) user-friendly platforms like Netflix and Hulu. When the streams do work, they are still marked with reminders that the viewer is accessing something that is not, strictly, meant for her. Soccer matches are emblazoned with onscreen bugs for Sky Sports and European satellite channels, and baseball games are accompanied by affiliate call signs and local advertisements from New York or Kansas City. Emblems of US TV’s network-affiliate structure evoke longstanding broadcasting traditions, but the experience of watching a television program meant for a different local market can be a jarring reminder of the deterritorialization inherent in contemporary online viewing. Other streams contain additional signifiers of forbidden viewing. A common source of unauthorized pro basketball livestreams, NBA International League Pass replaces commercials with internal jumbotron feeds portraying arena entertainment like halftime shows, cheerleaders, tee-shirt cannons, and kiss cams. Viewers are also liable to hear the occasional announcer speaking into a live mic and witness the production team testing out post-commercial-break highlight reels.

Unpredictable viewing experiences are a by-product of the work that goes into producing and distributing livestreams. Ranging from relatively cheap practices like plugging coaxial cables into digital adapters to more complex forms of signal hacking and decryption, unauthorized TV circulation requires new kinds of intermediaries who are willing and able to transmit television feeds by whatever means available. While pirated livestreams are occasionally lacking in audiovisual definition, they are characterized by often-ingenious procedures that blur the lines among production, distribution, and consumption. For instance, livestreamers may go so far as to patch together hijacked signals of arena video feeds with audio from radio broadcasts and then circulate links via message boards and Reddit threads.

The Personal is Piratical

Other sources of live piracy do not require such technological know-how, nor are they as closely connected to the extensive, global shadow economies of livestreaming that have developed over the last several years. Increasingly, one major way that people access pirate feeds of events like the Olympics, English Premiere League soccer matches, or pay-per-view programs is by watching individual users’ feeds on nominally personal livestreaming platforms like Periscope, Facebook Live, and the now-defunct Meerkat. By pointing a phone’s camera at the TV set, anyone can theoretically become a de facto broadcaster—at least until the stream is discovered and shut down.

These streams are not only live in a temporal sense, but also in their experiential, personalized liveness. As Adam Rugg and Benjamin Burroughs have pointed out, Periscope livestreams are characterized by a tension between the intimacy of the individual livestreamer and the potentially global circulation of streaming video. [3] Shaky, handheld iPhones, background noise, ad hoc commentary, and other markers of small-scale, amateur media production commingle with the massiveness of a media event like, say, the Super Bowl.

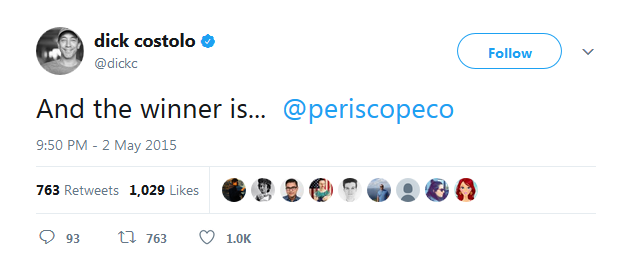

Because this kind of livestreaming blends television broadcasting with the more banal, personalized act of social sharing, it’s easy to presume that individual users share livestreams for the familiar goal of exposure. A New Yorker piece on the widely livestreamed 2015 Floyd Mayweather/Manny Pacquiao fight suggested that one Periscope user who streamed the event from inside the arena risked ejection and legal troubles all “for the glory of a stream and some followers.” At the same time, pirated livestreaming inverts social media’s usual economy of attention and likes. Because Periscope and Facebook locate unauthorized broadcasts in part by tracking which streams receive higher numbers of views and likes, the entrepreneurial work of posting pirate livestreams must toe a line between offering viewers something they want and staying somewhat discreet.

Disruptive or Traditional?

Pirated livestreaming might strike us initially as a disruptive technology, and there’s an argument to be made that in many ways it is. After all, it potentially draws viewers away from formal media economies and makes an antenna or cable subscription less essential. At the same time, it articulates digital piracy—again, a nominally asynchronous experience—to a traditional understanding of television as a live, communal experience. Thus, unauthorized livestreaming evokes familiar TV experiences even as it forsakes the television industries’ dominant economic models.

Pirate livestreaming also fits into a deeper history of unauthorized media practice. While the specific forms of illegal livestreaming discussed here are relatively new, they recall earlier intrusions on the television industry’s careful management of spatial and temporal control. For instance, pirate radio, analog television signal hijacking, and tapping cable lines were also based in logics of liveness and simultaneity. In a pre-time-shifting era, practices like stealing cable and decrypting satellite feeds served the same purpose as the livestreaming platforms discussed here. But because piracy over the last couple of decades has been considered primarily in the context of illegal digital commodity exchange, it has at once become disassociated with liveness and invoked as a symptom of individualized (or, less charitably, selfish) on-demand media culture. This ignores a long tradition of pirate media as a live, collective experience sustained in part through the work of everyday users and hobbyists—a tradition that continues in today’s unauthorized livestreaming.

Image Credits:

1. Digital Piracy

2. Popular Illegal Streaming Site (Author Screenshot)

3. Malware Warning Image (Author Screenshot)

4. Periscope Image

5. Costolo Tweet (Author Screenshot)

Please feel free to comment.

- I recognize the loaded ideological nature of the term “piracy,” and I don’t want my use of the term to suggest a value judgment on the practice. After all, informal media circulation and use are diverse and multitudinous in their practices and politics. I use the term here primarily for the sake of simplicity and readability. [↩]

- Amanda D. Lotz, Portals: A Treatise on Internet-Distributed Television (Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9699689. [↩]

- Adam Rugg and Benjamin Burroughs, “Periscope, Live-Streaming and Mobile Video Culture,” in Geoblocking and Global Video Culture, eds. Ramon Lobato and James Meese (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2016), 65. [↩]

Pingback: IPTV Piracy and Global Television Distribution Ramon Lobato / RMIT University – Flow