Comics ↔ Media: Comics Aren’t Literature, and That’s Fine

Benjamin Woo / Carleton University

As a life-long reader of superhero comic books, I have an abiding belief in the importance of origin stories.

When I was an undergraduate student, I was told a story about the history of my field—in Canada, at least. It was a story of how a tradition of inquiry based in fandom became institutionalized in universities when faculty in English departments began to grapple with the cultural forms that were competing for their students’ attention. First came the cinema, and then the panoply of newly “new media”: television, video games, web-based video, social media, and so on.

This origin story is not unlike that of comics studies. [1] It, too, has its robust tradition of fan scholarship. And it too has been deeply shaped by its association with literature departments, but, notwithstanding the comics studies groups within the Society for Cinema and Media Studies and International Association for Media and Communication Research and the growth of standalone learned societies like the Comics Studies Association and the Canadian Society for the Study of Comics, it remains essentially a branch of literary studies. Moreover, because of their relatively marginal position within the more established discipline, many comics scholars (especially, students in programs that lack a deep bench of supervisors working in popular literatures) end up reproducing literary studies’ most conservative paradigms, staking a claim for comics’ inherent quality to justify their place in a university classroom or scholarly journal. [2]

I fear that this equation of aesthetic with scholarly value impoverishes the field at precisely the time when it needs to be its gutsiest. This is not a time for retreat into media-specific silos. So, as Flow goes through a similar process of re-orientation, I want to use my columns this year to reflect on the relationship between comics studies and media studies, more generally: What would it mean to consider comics as media, and what might we gain by drawing comics studies and media studies into closer alignment?

The gentrifying labels of “graphic novels” and “graphic narrative” seek to re-shape comics into plausible texts for literary study. But, as media and as culture, they quickly overflow the container of the literary text. [3]

Literature is, perhaps first and foremost, the product of an author, and authorship remains a key organizing concept. Comics almost systematically frustrates this. Most comics have been the product of creative teams of writers and pencillers and inkers and colorists and letterers, to say nothing of the editorial, production and business staff who make publishing a comic book possible. Some traditions of cartooning do offer figures that can be taken for authors or auteurs. Someone who both writes and draws their comics—a Spiegelman or Bechdel, for instance—seems to exert the level of autonomy and control we demand of a literary author. Even then, the literary framing tends to focus scholars’ attention on the words they write more than the pictures they draw or the myriad interrelations of text and image in space.

In doing this work, most comics creators have been more oriented to the market and audience demand than the ideal-typical literary author is imagined to be. In Bourdieusian terms, comics as a whole lies closer to the heteronomous pole than the autonomous one. Grappling with this means accounting for seriality, circulation, and the fact that most comics are not remarkable or even all that good. We need to look not only at the few, precious pearls but also the big pile of empty oyster shells. Dale Jacobs’s current project to analyze every comic book published in America during the bicentennial year of 1976, the critic Douglas Wolk’s effort to read every Marvel comic book, and the What Were Comics? project are all attempts at a different mode of reading and a different method for apprehending comics as eighty years of output from a cultural industry.

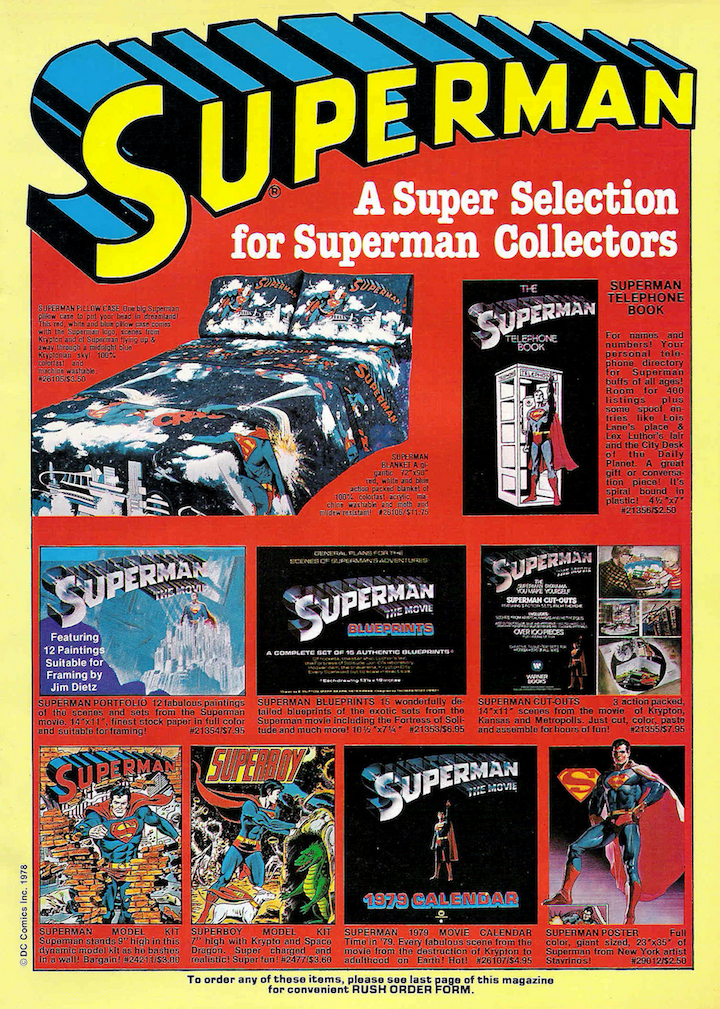

But the comic book industry is not exactly like other publishing industries, and it would be a mistake to think its products are “books” or “magazines.” Ian Gordon’s recent book on Superman, for instance, raises questions about just what Superman is. Gordon eventually settles on the term “icon” to describe the bundle of symbols, characters, settings, narrative devices, and themes brought together under the sign of a big red S. [4] If the concept of transmedia represents a network of adaptations in which no text has the privileged status of “original,” then comics were transmedia avant la lettre. Their publishers are in the business of maintaining a database of narrative and aesthetic elements that can be endlessly recompiled into new media products: one Harley Quinn for tween girls and another for allegedly grown men appearing across a range of platforms. [5]

Scholars have pointed to the increased articulation between the comic book industry and Hollywood in the form of adaptations of superhero comic-book franchises. [6] There is undoubtedly something to this, but histories of early comic art show this is hardly a new phenomenon. [7] Within two years of Superman’s debut, for example, the company that would become DC Comics had already established Superman, Inc. (later known as the Licensing Corporation of America) to manage its valuable intellectual properties, and its business manager Jack Liebowitz was one of the architects of the Warner Communications conglomerate. [8] “Comics” don’t stop at the edge of the page; we have to follow the transmedial object as it spreads promiscuously through our media culture.

In “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” Michel Foucault warns that a focus on origin stories makes for a bad philosophy of history. The comics-as-literature discourse provided comics studies a point of departure but it can’t remain our primary frame of reference. After all, comics isn’t a genre of literature.

Comics is a cultural form that circulates through a range of media (newspaper strips, periodicals, codex books, and web sites, apps and social media) and enrolls various publics—creators, industrial actors, retailers, critics and scholars, audiences and fans, re-mediators and adaptors—into specific media-oriented practices. Consequently, we’ll need a big and truly interdisciplinary toolkit to apprehend it.

Image Credits:

1. Still from Adventures from Superman TV series, (1952-1958).

2. Ad for novelization of The Death and Life of Superman.

3. Cover, Superman Salutes the Bicentennial (DC Comics, 1976).

4. “Superman merchandise, 1979” uploaded to Flickr by Tom Simpson.

Please feel free to comment.

- Bart Beaty, introduction, IN FOCUS: Comics Studies: 50 Years After Film Studies, Cinema Journal 50, no. 3 (2011): 106–10. For some resources towards an alternative genealogy, see Matthew Smith and Randy Duncan, eds., The Secret Origins of Comics Studies (New York: Routledge, 2017). [↩]

- Bart Beaty and Benjamin Woo, The Greatest Comic Book of All Time: Symbolic Capital and the Field of American Comic Books (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). [↩]

- Christopher Pizzino, Arresting Development: Comics at the Boundary of Literature (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016); Andrew Hoberek, “Coda: After Watchmen” in Considering Watchmen: Poetics, Property, Politics, 159–83 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2014). [↩]

- Ian Gordon, Superman: The Persistence of an American Icon (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017). [↩]

- Adam Arvidsson, Brands: Meaning and Value in Media Culture (New York: Routledge, 2006); Hiroki Azuma, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals, trans. Jonathan E. Abel and Shion Kono (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009). [↩]

- See, e.g., Liam Burke, The Comic Book Film Adaptation: Exploring Modern Hollywood’s Leading Genre (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015); Blair Davis, Movie Comics: Page to Screen / Screen to Page (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017); Alisa Perren and Laura Felschow, “The Bigger Picture: Drawing Intersections Between Comics, Fan, and Industry Studies,” in The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom, eds. Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott (New York: Routledge, 2017). [↩]

- Jared Gardner, Projections: Comics and the History of Twenty-First Century Storytelling (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012); Ian Gordon, Comic Strips and Consumer Culture, 1890–1945 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998). [↩]

- Gordon, Superman, 106, 9. [↩]

Pingback: Listening—Finally—to Soundtrack Albums Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University – Flow

I appreciate you sharing this article.Thanks Again. Much obliged.

its a nice article.traveling is the best thing that makes you enjoy very well. to explore the magic of Dubai by the ba href=”https://www.ubltravels.com”>best travel agency in Dubai with low price . enjoy every moments in life by traveling

It’s bizarre how a comics article is full of spammy comments. I see that, in the English speaking community this topic is still not resolved, where the discussion goes to minutiae. Either the quality of comics (there is tons of bad literature) or the fact that one reads it (a Shakespearean play should not be considered literature, then, because the public is watching it, not reading) are the main “arguments”. Both are shaky at best.

I think the best argument is that comics need images, whereas literature consists on words. There are some intermixing (a book can be illustrated, a comic book can have text), but overall they have different languages.