The Personal Is Digital: Exploring Race, Beauty and Hair Online

Briana Barner/ University of Texas at Austin

Hair care company Shea Moisture quickly learned the power of a viral ad when one of their recent digital commercials caused much controversy. It debuted on the heels of another viral ad that caused similar controversy: Pepsi’s ill-fated protest commercial that starred Kendall Jenner. What the two commercials have in common is that there was an almost-immediate online backlash to the ads’ content: both attempted to deal with racially sensitive issues. Pepsi’s ad staged a protest that ended with Jenner handing a cop…a Pepsi. Shea Moisture’s ad featured a concept they called “hair hate,” which will be explored throughout this article.

According to scholar Joanna L. Jenkins, Black women have had a contested relationship with advertising. During enslavement, they were advertised in local media as commodities and wenches to be both physical and sexual property during slavery. Jenkins writes that “advertising proliferates portrayals of people of color, such as Black women, that reflect the perceived values and norms of general market audiences”1 Images are a key component of advertisements, and are also key components of ideologies about race present in media. Media then helps to construct ideas about race.

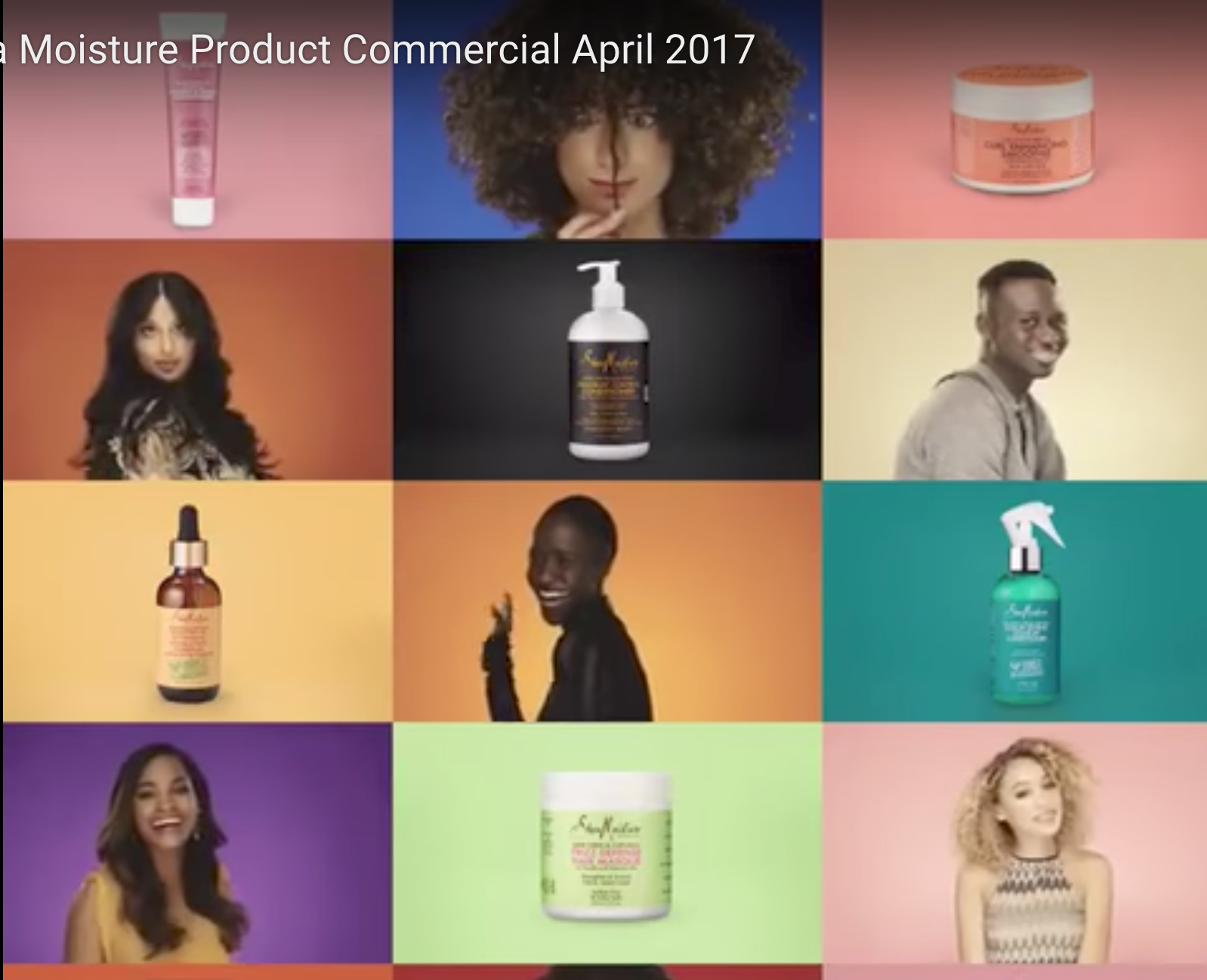

The Shea Moisture commercial was released on their social media platforms on April 24, 2017. Within hours of its release, the company removed the commercial and quickly released an apology on their Facebook page. The company has utilized social media as a way to connect with its loyal users, who they said in one Facebook post, utilized their brand even when they were selling their merchandise on the streets of New York. Those same customers took to the company’s Facebook page to express their hurt and disappointment over the commercial by leaving very detailed 1-star reviews. One of those reviews, which was written the day after the commercial was released, stated the following:

Race and beauty have become digitized, to echo Lisa Nakamura, and in the wake of this, online spaces have become spaces to share information but to also exercise buying power and to influence others to do the same.2 Several bad reviews on social media is bad business for any business—Shea Moisture now has thousands of them. Joanna Jenkins states, “The Internet has become a form forum for communities to mobilize their collective voices to support causes they care about, increase philanthropy and use consumerism for good…Advertising has become increasingly participatory. As a result, advertisers are being held accountable for their choices in real time.”3

The ad featured three women discussing “hair hate.” Two of them were White women—one with blonde hair and one with red hair. The third woman had long, curly dark hair and appears to be a woman of color. The commercial begins with her saying, “People would throw stuff in my hair and there would be like, little paper balls in my hair. I hated it because I have this (pointing to her hair) and people make fun of me for it.” The next image are words that say, “Fact: Hair hate is real.” This implies that the treatment that the previous woman described is to be understood as “hair hate,” though it is never explicitly defined.

Next, the woman with blonde hair states, “It was a lot of days of staring in the mirror going, ‘I don’t know what to do with it.’” She points to her hair, similar to the previous woman with the curly hair. Finally, the woman with the red hair says, ‘I didn’t feel like I was supposed to be a red head. I dyed my hair blonde for seven years of my life. Platinum blonde.” She emphasizes the last two words with a knowing glance toward the camera, to signal the incredulity of dying her hair that color. The camera returns back to the woman with darker hair as she says, “I didn’t embrace my hair. But as I got older I learned how to do it and learned how to love it.” The following scene has these words in big letters: “Break free from hair hate.”

The commercial ends with the hashtag #EverybodyGetsLove. #EverybodyGetsLove, the commercial insists, but there is a noticeable absence of the women of color who made the product popular. “Embrace hair love in every form,” the commercial states before including brief images of a more diverse group of people. But there is not an embrace of a variety of hair types in the commercial. The main models all have long hair, and the only one with curls, has very loose, almost wavy curls—unlike the tighter coiled hair of many of the Youtube hair vloggers who do reviews of Shea Moisture’s products. There is a small but growing portion of health and beauty aisles in major stores like Walmart and Target that cater to “Ethnic Hair Care.” For Black women, wearing their hair in its natural state requires not only the right hair products but acceptance in some form. Being “natural” is an identity that connects Black people to others doing the same, wearing their hair in styles that are in direct opposition to mainstream ideals of beauty.

In a Facebook post written in 2016 after there were concerns that the company would no longer prioritize the women of color consumers the brand seemed to target, the company stated:

The hair hate discussed in the commercial minimizes the actual discrimination and prejudice that Black women face solely because of their hair. Congresswoman Maxine Waters provides a great example of this. Despite challenging an administration that puts the lives of many at risk with their racist, sexist, ableist, Islamophobic and homophobic rhetoric, Waters was disparaged by Bill O’Reilly because he did not find her hair appealing. We can also look at the many states in which dreadlocks can be a reason to discriminate against a potential employee.

It is important to acknowledge the role that the Internet played in this controversy. Lisa Nakamura writes: “Mediated conversations about race, whether on the Internet with human interlocutors or with the torrent of digitized media texts, have become an increasingly important channel for discourse about our differences. Race has itself become a digital medium, a distinctive set of infomatic codes, networked mediated narratives, maps, images and visualizations that index identity.”4 Black women have used their collective voices to fight back against harmful ideologies of erasure and the minimizing of issues important to them. Within hours of both the release of the commercial and the apology, many declared on various social media platforms and thinkpieces that Shea Moisture had been “cancelled,” and began highlighting other Black-owned hair care lines. Only time will tell if this does long-term damage to their brand, but it is a lesson that harmful ideologies can now be addressed and protested within hours of them spreading.

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screen grab.

2. Author’s screen grab.

3. Author’s screen grab.

4. Author’s screen grab.

Please feel free to comment.

- Jenkins, Joanna L. “Apparitions of the Past and Obscure Visions for the Future: Stereotypes of Black Women and Advertising during a Paradigm Shift” in Black Women and Popular Culture, ed. Adria Y. Goldman, Lexington Books, London, 2014, pp. 199-233. [↩]

- Nakamura, Lisa and Chow-White, Peter A. “Introduction: Race and Digital Technology.” in Race after the Internet, eds. Lisa Nakamura and Peter A. Chow-White, Taylor and Francis, Hoboken, 2011, pp. 5. [↩]

- Jenkins, 217. [↩]

- Nakamura and Chow-White, 5. [↩]

Hello, Just a great article or information. Hope you will sharing new article or post in future. Great post. I found your website perfect for my needs. Thank you for sharing with us. I would like to thank you for the efforts you have made in writing this article. I am hoping the same best work from you in the future as well. Company Registration Services in India I enjoy the content and in particular the content where you’re making clear explanations of things that no one else really makes clear…

If a system is occurring in the digital realm that collects private statistics, publishes non-public facts, tracks personal actions, shares non-public facts, enters private space, and/or implements your personal identification, then I could say privacy concerns arise.

Hello! I have got great news for people who struggle with writing papers. You can apply to the writing service and find there all the necessary information.

thanks a lot for this wonderful information. I really liked it a lot.