Sonic Cute: An Overview

Anthony P. McIntyre / University College Dublin

In this my final column on the theme of cuteness for Flow, I’m going to give a brief overview and sketch out some possible avenues for further research in an area relatively neglected by scholars of the aesthetic: cuteness and popular music. Even a cursory consideration of pop music reveals how intrinsic cute aesthetics are in terms of both sound and image. Sonic cute, as I term it, has exerted a considerable influence on popular music and its associated visual texts for some time in ways that index complex questions of gender, power and representation.

A useful study by David Huron, in an analysis clearly influenced by the ethological roots of cuteness scholarship (notably the work of Konrad Lorenz), foregrounds how the high–pitched sonic emissions of young animals are liable to elicit “parenting behavior” and music or sounds that emulate this elicit a similar response from the listener.[1] As the author notes: “auditory cuteness appears to be a particular combination of acoustical features involving high spectral resonances and low amplitude. But the distal cause of auditory cuteness is the promoting of parenting behaviors — presumed to be directed at human infants.” In our recent volume, The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness, my co-editors and I have sought to consolidate existing scholarship and push the understanding of cuteness beyond one that is predominantly centred on the notion of parental response (not to say that this is not sometimes the case) and open up critical analyses to elements such as the assymetrical power relations (Ngai), invocations to play (Sherman and Haidt), as well as the vast array of sexual and racial connotations that cohere in a wide variety of cute texts. It is this set of conceptual concerns that I briefly seek to position in regard to cute pop music and its associated set of visual texts in this article.

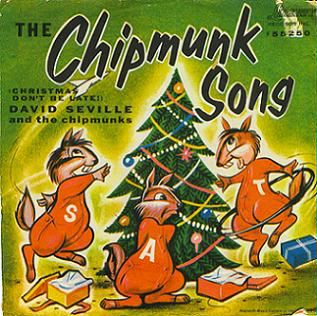

If we return to Huron’s description of cute sound, we see its value in tracing a history of sonic cute in popular music. Taking as a prime example Alvin and The Chipmunks, a pop cultural phenomenon that began in 1958 when Ross Bagdasarian Sr. recorded and released “The Chipmunk Song (Christmas Don’t Be Late),” we can see the “high spectral resonances” Huron identifies are in this case manifest in Bagdasarian’s pioneering usage of the “varispeed” recording technique that produced the distinctive high-pitched “Chipmunk sound”[2]. The hit record spawned a franchise featuring the anthropomorphic cute rodents that thrives to this day with current animated television series Alvinnn!!! And the Chipmunks (2015–) and the recent feature Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip (2015) just the latest in a long line of Chipmunk media texts. I’ve previously written of cuteness’s connection to anthropomorphized animated animals, and the longevity and transmedia success of The Chipmunks are indicative of the commercial logics identified as key features of the aesthetic.

Bagdasarian’s creation also suggests that cuteness is a viable aesthetic strategy in the creation of fluid identity positions that reject standard markers of rock and pop authenticity. Bagdasarian, U.S. born and of Armenian heritage, voiced not only the three chipmunks (Alvin, Simon and Theodore), but also their companion, David Saville (the producer’s long-standing stage name). In this way, we can see how the Chipmunks with their cute-ified vocals were a precursor to many of the experimental and often critically lauded developments in pop music in recent years. Indeed, composer and musicologist Nick Collins accords the Chipmunks a seminal position in an article tracing a genealogy of “virtual musicians,” seeing the high-pitched children’s favorites as precursors of contemporary post-human pop entities such as Gorillaz (the fusion of animation and collaborative music perhaps best-known as a side-project of Blur frontman Damon Albarn) and the “virtual idols“ who top the music charts in Japan.[3]

This confluence of technological development and cute-ified pop cultural aesthetics is also evident in the self-consciously artificial audio-visual style of artists associated with British music label PC Music. “Hey QT” by QT, for instance, an underground hit from 2014, clearly has Bagdasarian’s varispeed vocals in its sonic DNA, and is representative of a whole host of artists on the label whose common denominator seems to be pushing cute aesthetics to their limits. Artists such as GFOTY (Girlfriend of the Year), Hannah Diamond, and the producer largely responsible for “Hey QT,” SOPHIE (who despite the female-gendered name is a London-based male) all use high-pitched vocals and channel a plethora of influences such as J-Pop, happy hardcore and UK garage into their music and for a while polarized opinion as to whether they constituted, in the title of one article, “the future of pop or [a] contemptuous prank?” This polarity of response, is perhaps to be expected, given the centrality of cute to PC Music’s sound. Sianne Ngai, for instance, categorized cuteness as an aesthetic that transparently manipulates our responses, leading as much to aggression on the part of the perceiving subject (squishing the cute frog face of a sponge in her example) as a positive care-giving response.[4] While this aesthetic judgement occurs within reason (as Joshua Paul Dale wittily puts it, “the world is not knee-deep in dead babies and puppies” [5]), it does go some way to explaining the extreme love-hate positioning much of the music press took toward PC Music’s roster of artists, or even why Alvin and the Chipmunks are commercially successful but, for the most part, critically held in contempt, an attitude that might account for the dearth of scholarship on the band/brand.

“Hey QT” was initially posited as a song about a fictional energy drink, evident in the website set up to promote the track, with an added twist being that its eventual underground success enabled the production of the canned drink (albeit in a limited and high-priced run). This development led some to suggest that the whole enterprise was a marketing stunt by Redbull, the energy drink brand who sponsored some subsequent PC music events, an interpretation denied by the label. [6] With QT, whose real name the website credits as “Quinn Thomas, Founder of QT,” discerning truth from fiction seems to be part of the attraction, with one journalist describing her as “an artist who seems halfway between a product and a prank.” [7] While it might be overstating the case to label the song subversive, it does seem to be particularly timely, suggesting through the construct of QT that, in accordance with Sarah Banet-Weiser’s assessment of contemporary postfeminist media cultures, cultural participation is “increasingly only legible in the language of business.” [8] The song’s overtly manipulated vocal track, borrowing heavily from the kawaii conventions of J-pop (see Keith and Hughes [9], for a detailed analysis of vocal styles in this pop genre) combined with the strangely flattened affect of the central performance in the video, denoting artificiality through the virtual reality space within which QT seemingly exists, foreground the ambivalent positioning of the piece, a quality that further corroborated interpretations of the song and QT as a thinly veiled critique of contemporary consumer society.

The final artist I consider speaks to the ambivalence of cuteness and how this aspect of the aesthetic can resonate with the star text of a recording artist, becoming central to both image and sound and in the process recalibrating existing gender scripts. While the artists associated with the PC Music label have their own ambivalent positioning within the realm of gender politics, Shamir, the recording name of Las Vegas singer and performer Shamir Bailey was for a time around the release of his 2015 debut album, Ratchet, fêted both for the fresh pop sound on his record, but also the “post-gender” cultural trend the young singer supposedly seemed to encompass. The title of a prominent feature in The Advocate, for instance, asked, “Is Shamir the Post-Gender Pop Star for Our Time?” while many other features on the young musician quoted an emoji-ed tweet he posted reading, “To those who keep asking, I have no gender, no sexuality and no fucks to give.”[10]

Perhaps most notable in this coverage of the musician was the sustained emphasis on how well-adjusted this genderqueer artist was, a discourse discursively linked in most pieces with his generational status as a millennial. An article in the Guardian, for instance, described Shamir as “a post-gender, androgyne angel of a millennial” and commented on how he hadn’t been bullied in school, was voted “best dressed”, “most likely to appear on the cover of Vogue”, and even nominated for “Prom King” in his final year in high school[11]: All seemingly indicators of the balanced and likable nature of the young performer. Likewise, a Pitchfork article on Shamir opines, “image work is easy for millennials, who can often seem omnivorous and guided less by the dividing lines of politics than the universal high of being really into stuff. Shamir knows who he needs to be for the camera and transforms without suffering” (final emphasis mine)[12]. Perhaps implicit in this commentary seems to be an acknowledgement of the distance between Shamir’s poppy sound and upbeat attitude and that of genderqueer performers of an earlier generation such as Anohni, from Antony and the Johnsons, whose melancholic records such as 2005’s I am a Bird Now circled themes of transformation and duality.

This discursive construction of Shamir as well-adjusted and fluidly transformative, is closely imbricated, I would argue, with the qualities of sonic cute evident in his recorded music of this era and also in the surrounding texts that matched image to sound. Just as in the examples of Alvin and the Chipmunks and QT detailed earlier, vocal timbre is a key factor in this aural iteration of cute aesthetics. Shamir ‘s voice is often termed “androgynous falsetto” and while not as high pitched as the two earlier examples, it is often multi-tracked (layered) to give it a girlish quality, as in “On the Regular”. If we consider the screenshot from the music video for On The Regular (above) we see how in keeping with the rest of the video, bright colors are used to complement the song, an arrangement that makes ample usage of the “high spectral ranges” Huron previously noted as common to sonic cute. Similarly, the use of a Fisher-Price toy fits with a lyric in the song, but also connotes an invocation to play, a feature that psychologists Gary D. Sherman and Jonathan Haidt posit as a more accurate representation of cuteness’s power over a perceiving subject than the “parental instincts” suggested by early ethologists. [13]

This quality of cuteness is foregrounded even more in the video (above) for “Call It Off,” where the artist is literally cute-ified over the course of the video, transformed into a puppet, or more specifically a Muppet as it was Jim Henson’s workshop responsible for the manufacturing. Again, the video’s aesthetics rely on the use of day-glo and primary colors in its later sections, matching the high-range foregrounded in this recording and the cumulative effect of these initial songs and videos created a cute star image for the young singer.

Perhaps, however, the color-saturated extremes of cuteness as exemplified in much of the artist’s work of this time were too blunt to fully encapsulate the complexity of Shamir’s vision, or overwhelmed other aspects of the artist’s oeuvre. A feature-writer for music website Pitchfork certainly picked up on this, and the imposition of this image on a neophyte artist by older professionals in the industry, when on location for the filming of “Call It Off”.

“I see the puppet and suddenly the video shoot seems farcical and weird, an expensive ordeal orchestrated by a bunch of market-savvy people in their 30s and 40s trying to harness the natural charisma of a 20-year-old kid who is grateful for the fairytale his life has become and yet who at times seems supremely bored by it, or at least confused as to what the fuss is about.” [14]

Certainly, Powell’s analysis seems poignant and insightful given the fact that, as I was writing this article Shamir, dropped from British label XL, self-released a free album, Hope, along with a message suggesting a discomfort with how his image had previously been presented. The artist relates how he recorded the present album over the course of the week after a period where he almost quit making music as “the wear of staying polished with how im presented and how my music was presented took a huge toll on me mentally. I started to hate music, the thing i loved the most!” While as I suggest, cute aesthetics, may, in a pop setting, enable a certain conceptual latitude that stretches the acceptable bounds of pop authenticity, in Shamir’s case it arguably presented an overwhelming, playful public persona that failed to tally with a heterogenous output that was intrinsic to the artist’s sense of artistic integrity.

Conclusion

While it is tempting to see in the manifestations of sonic cute charted in the case studies above evidence of cuteness’s ability to push the boundaries of notions of identity and gender (and species) performativity, this highly ambivalent aesthetic also displays an ability to flatten out expression so that it perhaps lacks nuance and can in its own way be restrictive and reinforce prescriptive social scripts. So, while some commentators have found the artists associated with the PC Music label as turning “the macho culture of so much dance and house music on its head”[15] others see the label as yet another instance of Svengali male producers’ appropriation of female artists and aesthetics [16], a phenomenon that has a sonic cute antecedent in Ron Bargdasian’s ability to technologically innovate and self-voice a set of anthropomorphized rodents and in the process instigate a family business and pop cultural phenomenon. Shamir’s initial records channeled a zetitgeist appetite for cute-inflected “post-gender” optimism that arguably restricted the artist’s own vision. It is perhaps this ambivalent power and the proximate aesthetic corollaries that are generated that mark sonic cute out as a topic worthy of further academic explication.

Image Credits

1: The Los Angeles Times

2: The Guardian

3: ADVOCATE

Please feel free to comment.

- David Huron. “The Plural Pleasures of Music.” Proceedings of the 2004 Music and Music Science Conference. Ed. Johan Sundberg and William Brunson. Stockholm: Kungliga Musikhögskolan & KTH (Royal Institute of Technology), 2005. 1-13. Print. [↩]

- Carpenter, Susan. “‘Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Squeakquel’ Soundtrack Scores.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 23 Dec. 2009. Web. 17 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Collins, Nick. “Trading Faures: Virtual Musicians and Machine Ethics.” Leonardo Music Journal 21.21 (2011): 35-39. Web. [↩]

- Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard UP, 2012. Print. [↩]

- Dale, Joshua Paul, Joyce Goggin, Julia Leyda, Anthony P. McIntyre, and Diane Negra, eds. The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness. New York: Routledge. 2017. Print. [↩]

- Vozick-Levinson, Simon. “PC Music Are for Real: A. G. Cook & Sophie Talk Twisted Pop.” Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone, 22 May 2015. Web. 17 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Wolfson, Sam. “PC Music: The Future of Pop or ‘contemptuous Parody’?” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 02 May 2015. Web. 17 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. Authentic TM: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture New York: NYU Press, 2012. Print. [↩]

- Keith, Sarah, and Diane Hughes. “Embodied Kawaii: Girls’ Voices in J-pop.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 28.4 (2016): 474-87. Web. [↩]

- Vivinetto, Gina. “Is Shamir the Post-Gender Pop Star for Our Time?” ADVOCATE. N.p., 14 May 2015. Web. 17 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Hoby, Hermione. “Shamir : ‘I Never Felt like a Boy or a Girl, That I Should Dress like This or That’.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 11 May 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Powell, Mike. “The Charmed (and Charming) Life of Shamir Bailey.” Pitchfork. N.p., 11 May 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Sherman, Gary D., and Jonathan Haidt. “Cuteness and Disgust: The Humanizing and Dehumanizing Effects of Emotion.” Emotion Review 3.3 (2011): 245–51. [↩]

- Powell, 2015 [↩]

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. “PC Music at SXSW Review – Good Taste Goes out the Window in Pop Makeover.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 20 Mar. 2015. Web. 18 Apr. 2017. [↩]

- Kretowicz, Steph. “You’re Too Cute: Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, SOPHIE, PC Music and the Aesthetic of Excess.” The FADER. The FADER, 01 Aug. 2016. Web. 17 Apr. 2017. [↩]