Power-Knowledge in a ‘Post-Truth’ World

Roopali Mukherjee / CUNY, Queens College

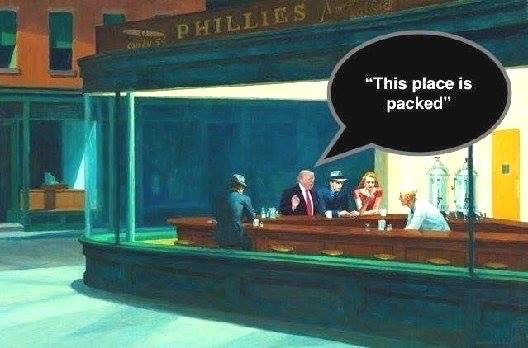

Days after the 2016 US elections, The Poke invited readers to send in renderings of famous Western artworks that photo-shopped or otherwise incorporated newly elected Donald Trump into them. Collected under the hashtag #TrumpArtworks, scores of images, smarting with sarcasm and contempt, poured in, among them Joe Heenan’s revision of the 1942 Edward Hopper work, Nighthawks. In a send-up of Trump’s “alternative fact” about the size of the crowd at the inaugural ceremonies, Heenan’s revision seats Trump at the iconic late-night diner, announcing to the few patrons there: “This place is packed!”

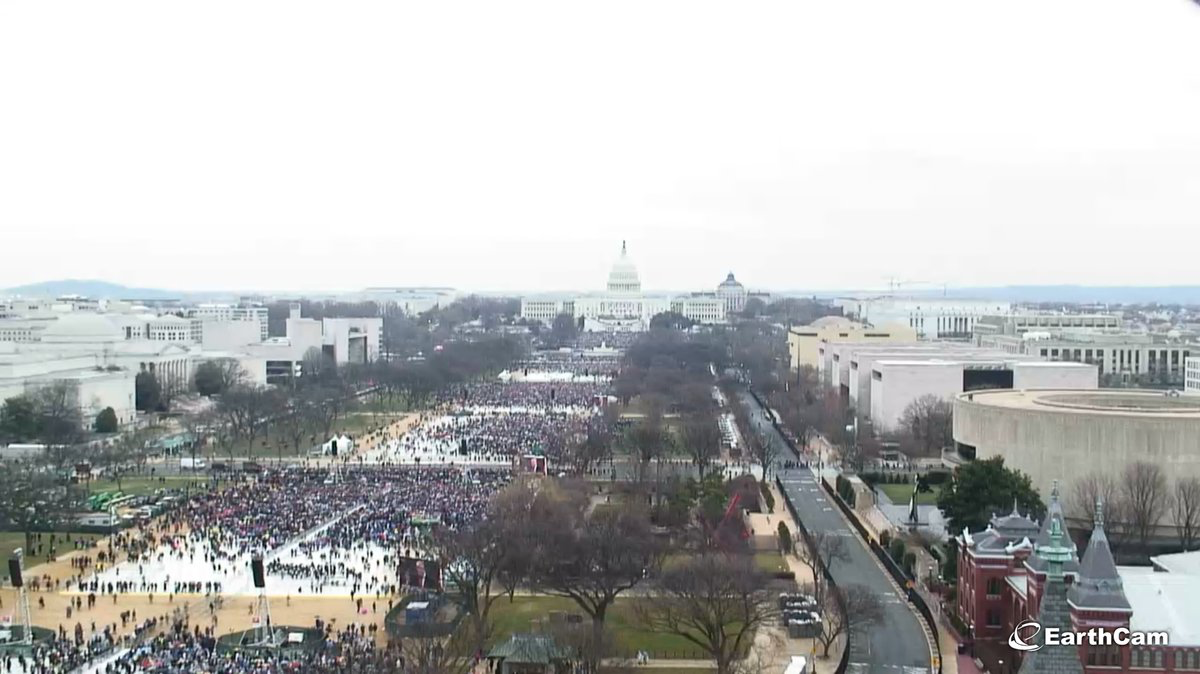

Answering Trump’s bluster that the inaugural ceremonies would gather his supporters in a rally that “would be the biggest of them all!,” mild-mannered Bernie Sanders responded with a side-by-side visual comparison, tweeting a rare jab: “They didn’t. It wasn’t.”

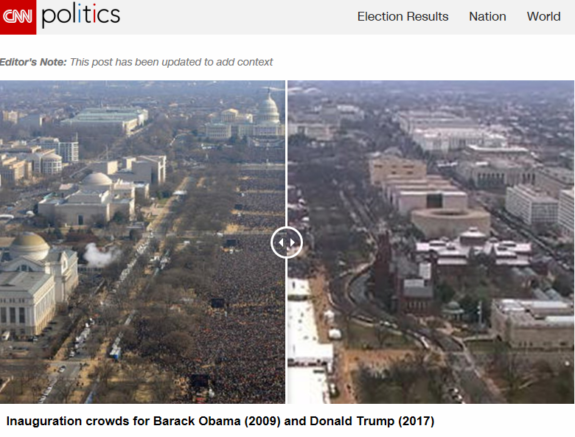

Within hours, CNN unveiled the now famous split-image comparison of aerial shots of Trump’s 2017 and Obama’s 2009 inaugurations, which showed, quite unequivocally, that the Obama crowds far outnumbered those that had assembled for Trump.

Gleefully re-tweeted across social media circuits worldwide, these responses join a nightly barrage of sharp-tongued television satire as well as a string of public condemnations – Meryl Streep, John McCain, and others – contributing to a glut of blistering commentary and satire. A catalogue of Trump’s characteristic lapses into invention and exaggeration, these rejoinders track prognoses of an alarming new “post-truth” or “post-fact” world. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] The willful spread of “rumor bombs” [8] [9] and “contrary facts of dubious quality and provenance” [10], the dangerous masking of propaganda as “fake news” and “alternative facts” [11] [12], each underscores the stakes of the post-truth/post-fact crisis. A sign of its permeation within the cultural milieu, popular use of the term “post-truth” grew by approximately 2,000 percent over the year, a spike that so distinguished the term that Oxford Dictionaries named it the 2016 Word of the Year.

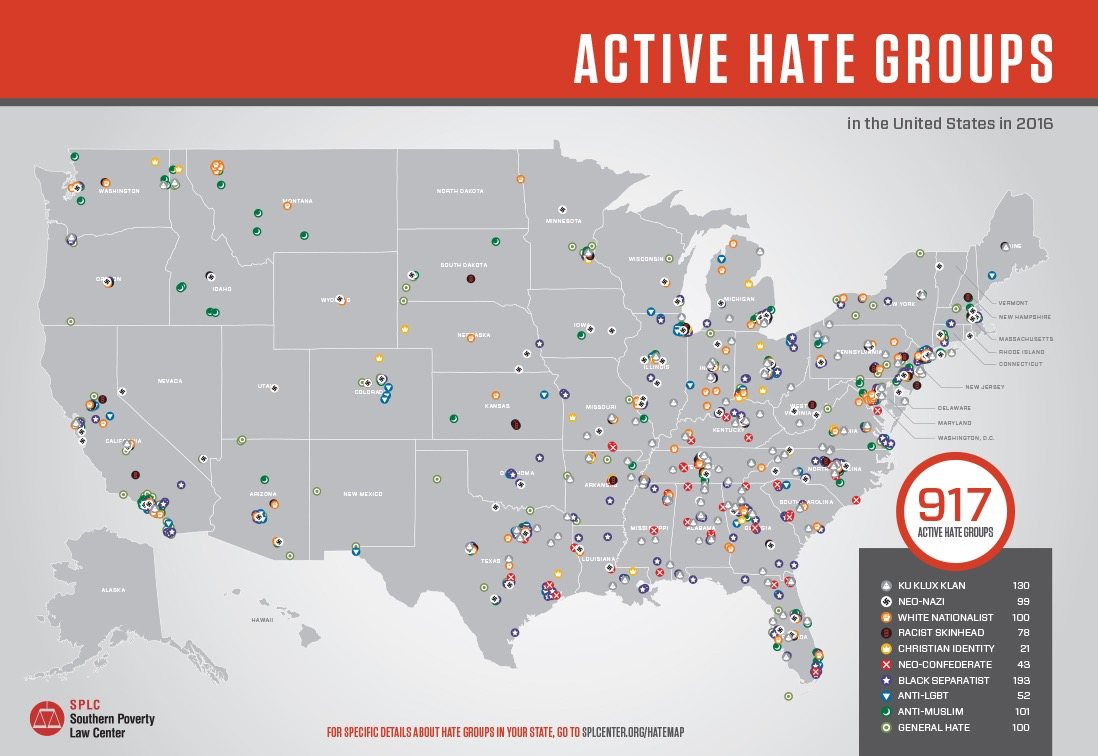

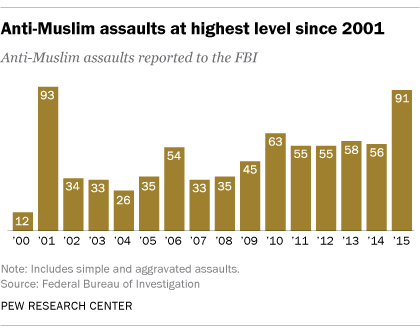

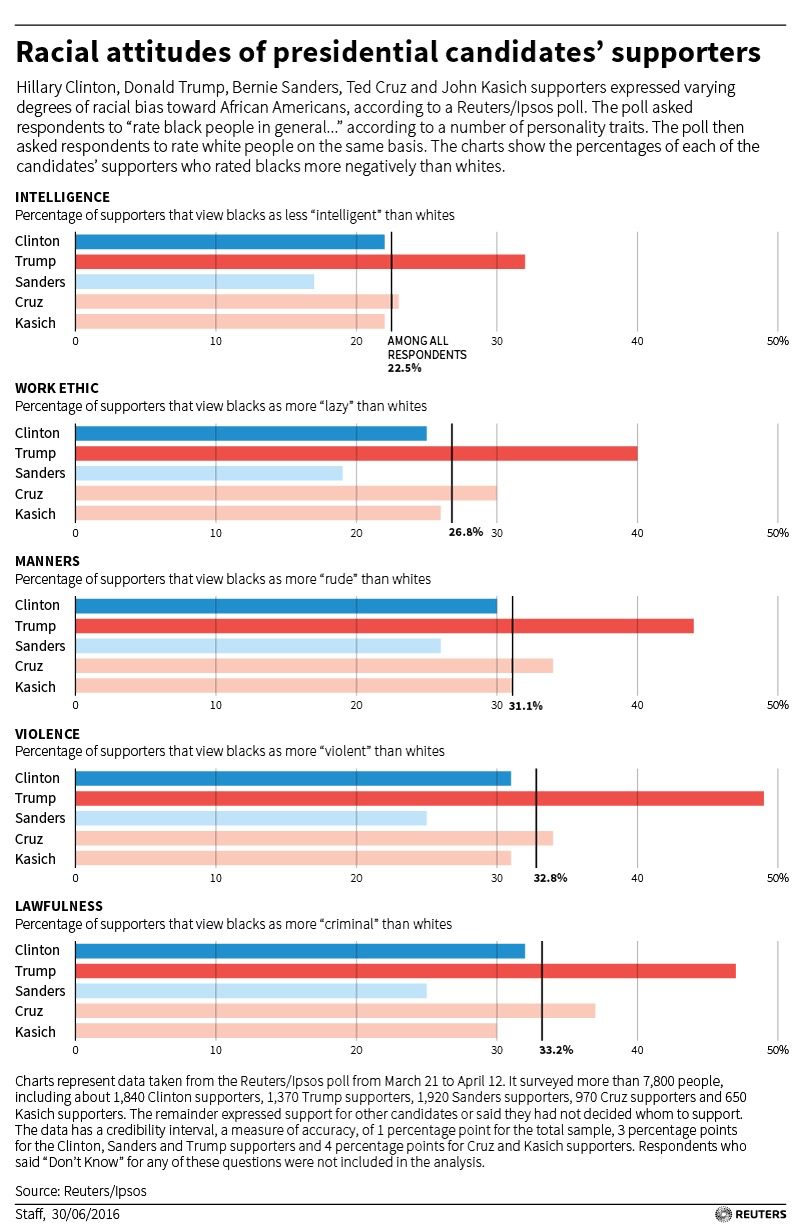

These shifts toward distortion, misrepresentation, and hyperbole have, in turn, spurred reprisals of a vehement facticity – vigilant repositings of verified and verifiable claims – via news reports, blog posts, social media updates, op-eds, scholarly commentaries, fact-check services – and a parade of data-heavy empirical forms including charts, graphs, interactive maps, timelines, testimonials, photographs, video and audio recordings, surveys, and interviews. Thus, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s HateWatch maps [13], Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King’s crowd-sourced USA Election Monitor [14], the Pew Research Center’s sobering graph showing anti-Muslim hate crimes escalating to post-9/11 levels [15], the Center for American Progress’s fact sheet on the costs of Trump’s deportation policies [16], the Reuters/Ipsos poll that documents high levels of anti-black sentiments among Trump supporters [17], each offers a painstaking compilation of figures, statistics, records, and documents as a demonstration of, and a prophylactic against, the administration’s dangerous disregard for facts and evidence.

The steady drumbeat of these data-heavy responses suggests a foreboding, a widespread unease, as if their testimonies must bark to drown out Trump’s machinery of dissemblance and exaggeration. Belting out refrains of reliable and replicable evidence, they labor to assert the disciplinary modalities of facts and truth as if, somehow, the formidable authority of these epistemic forms now needs shoring up and reassurance. Reiterating the ethical necessity of empirical, fact-based truths, each is, at once, an inoculant against and a wary admission of the bewildering specter of a post-truth/post-fact world.

Certainly, the fast-and-loose proclivities of the new administration deserve nothing less than relentless vigilance for they are, quite without doubt, opportunistic, irresponsible, and dangerous. But the post-truth/post-fact crisis also invites insights about a whole terrain of epistemic contestation that marks the authority of official knowledges precisely in their encounters with unpalatable counter-knowledges. The stakes of the current crisis, then, also allow us glimpses of the disciplinary modalities of facts and falsehoods themselves as categories of power-knowledge embedded within struggles authorizing some truths and repressing others, and enlisted to maintaining the dominant order.

The earliest salvo in Trump’s arsenal of reckless “truthiness,” as Stephen Colbert terms it, repeated the widely discredited but viscerally effective birther lie that the nation’s first black President was foreign-born. His assertion that Mexican immigrants are “rapists” and “criminals,” likewise, struck a chord, needing little factual footing to cement support for his candidacy. His claim to have watched “thousands and thousands of people” cheering in Jersey City as the World Trade Center buildings collapsed on 9/11 drew discursive life not from any basis in truth but from its cynical wink-and-nod appeal to anti-Muslim sentiment. Each of these declarations links Trump’s spectacular ascent to a series of racial, and reliably racist, assertions, each one resting not on the power of evidence but on that of gut-level, intuitive beliefs. The propagandist, know-nothing excesses of the Trump edifice, then, track, and are themselves tracked by, the genealogies of racial, and racist, epistemic orders, which with visceral obduracy – in the face of incontrovertible countervailing evidence – have long organized truth and fact as profoundly raced categories of power-knowledge.

How does the post-truth/post-fact crisis engage and mediate this racial order of things? How might we understand the predicaments of truth and fact, marked and haunted by racial counter-knowledges, which remain, in the main, repressed, dismissed as laughable, odd, impossible?

In a January 11, 2017 episode of the ABC sitcom Black-ish, the protagonist Dre Johnson (Anthony Anderson), confronted by a white co-worker despairing after the election, responds with an impassioned enumeration of bleak everyday truths about black life. [18] In a monologue accompanied by a montage of images representing black experiences, and featuring Billy Holliday’s brooding anti-lynching anthem Strange Fruit on the soundtrack – in effect, dossiers of stirring visual and sonic evidence – Johnson reposits the shameful record of the nation’s racial crimes to explain that Trump’s victory is no cause for heartache to a people for whom the system has rarely worked, and who have long suffered its brutality.

The scene choreographs a spectacular encounter between dominant and marginal truths, dramatizing the epistemic force with which empirical, fact-based evidence of enduring and persistent racial inequalities remain, for the most part, subordinated to dominant national scripts of a square deal and a fair share bolstered by smug Obama-era conceits of racial progress. Like the “Election Night” skit on NBC’s Saturday Night Live that aired days after the election, in which host Dave Chappelle pokes fun at the visceral sway of authorized truths about racially tolerant rather than blinkered white liberals, and sentimental attachments to an innocent rather than shameful national past, these are counter-knowledges that resonate within black public spheres but which remain, for the most part, assiduously silenced and marginalized.

Labored reiterations of empirical, fact-based truths in the current moment, then, are symptomatic, as the Black-ish episode proclaims, of “knowing what it [feels] like to be black,” of knowing the truth – about climate change, mass deportation, the Muslim ban – despite its dismissal or repression as laughable, odd, impossible. Confronted with challenges that have long bedeviled unpalatable racial knowledges, the current crisis underscores the ethical necessity of “deconstructive jolts” to the disciplinary modalities of what counts as fact and falsehood, and the hard work of opening to skepticism the armature of distortion and erasure necessary for maintaining the epistemic order of a post-truth/post-fact world.

Image Credits:

1. Joe Heenan, January 23, 2017. “This place is packed!” @ThePoke #TrumpArtworks. Author’s screen grab.

2. Bernie Sanders, January 20, 2017. Twitter.

3. CNN, January 20, 2017.

4. Southern Poverty Law Center, Spring 2017.

5. Pew Research Center Fact Tank, 2016.

6. Reuters/Ipsos. June 30, 2016.

7. Black-ish (TV series, Season 3, Ep. 12, “Lemons”), ABC, January 11, 2017. Author’s screen grab from YouTube.

Please feel free to comment.

- Belluz, Julia. June 28, 2016. “Do Brexit and Donald Trump prove that we’re living in an era of fact-free politics?” Vox. http://www.vox.com/2016/6/28/12046126/brexit-donald-trump-facts-politics [↩]

- Drezner, Daniel W. June 16, 2016. “Why the post-truth political era might be around for a while.” Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/06/16/why-the-post-truth-political-era-might-be-around-for-a-while/?utm_term=.9d9bce8b42bc [↩]

- Egan, Timothy. November 4, 2016. “The post-truth presidency.” New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/04/opinion/campaign-stops/the-post-truth-presidency.html [↩]

- Holland, Justin. November 30, 2015. “Welcome to Donald Trump’s post-fact America.” Rolling Stone. http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/features/welcome-to-donald-trumps-post-fact-america-w452917 [↩]

- Krugman, Paul. December 22, 2011. “The post-truth campaign.” New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/23/opinion/krugman-the-post-truth-campaign.html [↩]

- Manjoo, Farhad. 2008. True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society. New York: Wiley. [↩]

- Sirota, David. March 3, 2007. “Welcome to the post-factual era.” Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-sirota/welcome-to-the-postfactua_b_42527.html [↩]

- Harsin, Jayson. 2010. “That’s democratainment: Obama, rumor bombs and primary definers.” Flow, 13(1). http://flowtv.org/2010/10/thats-democratainment/ [↩]

- Harsin, Jayson. February 2015. “Regimes of posttruth, postpolitics, and attention economies.” Communication, Culture & Critique, 8(2): 327–333. [↩]

- Fukuyama, Francis. February 23, 2017. “The emergence of a post-fact world.” Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-emergence-of-a-post-fact-world-by-francis-fukuyama-2017-01 [↩]

- Soll, Jacob. December 18, 2016. “The long and brutal history of fake news.” Politico.com. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/12/fake-news-history-long-violent-214535 [↩]

- Stanley, Jason. 2015. How Propaganda Works. Princeton University Press. [↩]

- Southern Poverty Law Center, Spring 2017. Active Hate Groups in the United States in 2016 (Map). https://www.splcenter.org/hate-map [↩]

- King, Shaun. 2016. USA Election Monitor (Interactive Map). Ushahidi.com. https://usaelectionmonitor.ushahidi.io/views/map [↩]

- Pew Research Center Fact Tank, 2016. “Anti-Muslim assaults reach 9/11 era levels FBI data show.” http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/21/anti-muslim-assaults-reach-911-era-levels-fbi-data-show/ [↩]

- Edwards, Ryan and Ortega, Francesc. September 21, 2016. “The economic impacts of removing unauthorized immigrant workers: An industry- and state-level analysis.” Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/reports/2016/09/21/144363/the-economic-impacts-of-removing-unauthorized-immigrant-workers/ [↩]

- Reuters/Ipsos. June 30, 2016. “Racial attitudes of Presidential candidates’ supporters” (Chart). http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/rngs/USA-ELECTION-RACE/010020H7174/USA-ELECTION-RACE.jpg [↩]

- “Black resilience in America” (Post-election Anthony Anderson monologue). Black-ish (TV series, Season 3, Ep. 12, “Lemon”). ABC, New York, January 11, 2017. [↩]

I noticed that almost every example of counter-knowledge here is delivered through humor, from Heenan’s version of Nighthawks, to Biden’s burn of Trump, and Chappelle and Chris Rock’s pre-election awareness of racism on SNL. Dre Johnson delivers his speech on a sitcom comedy, not a drama. Is humor the most direct way for counter-knowledge from alternative public spheres to deliver “deconstructive jolts” to the mainstream?