Support Your Local Daughter: Celebrating Mary Tyler Moore’s Glimpse at Maternal Anxiety

Emily Hoffman / Arkansas Tech University

For a show with a single, childless, thirty-something woman as its protagonist, The Mary Tyler Moore Show grapples with the often fraught dynamic between mothers and daughters. Initially, Mary Tyler Moore teems with maternal anxieties in a way that overtly challenges the fallacy tacitly perpetuated by so many family sitcoms—that mothering comes naturally to women. Conflicts regularly arise from female characters’ struggles to parent their daughters and forge fulfilling relationships. Initially, the subject is introduced through Phyllis and Bess Lindstrom in “Bess, You Is My Daughter Now” (Season 1, Episode 3). Phyllis relies on “creative child rearing” books to encourage Bess’s independence, but when Bess chooses to live with Mary instead, she worries about being supplanted, about being just “the old drudge who cooks her meals and mends her tattered little clothes.” Moreover, she worries that Bess will “hate me for being weak.” Her fear that Mary thinks she is “a lousy mother” is clearly an opinion she has of herself.

Like many adoring fans of Mary Tyler Moore born too late to experience the show in its original cultural context, I began watching the endless loop of reruns airing on Nick at Nite in the 1990s. I laughed at Ted’s incompetent yet confident bluster, all the clever put-downs Murray and Lou made at his expense, and Mary’s disastrous dinner parties. Plus, Mary just seemed nice, and her wardrobe—all bold colors and bell bottoms—looked casually glamorous even from the considerable vantage point of two decades later. Now, however, as a single, childless, nearly forty-year-old woman, I still laugh at Ted and envy Mary’s style, but I am struck by its poignant, at times painful, insight into how mothers (and sometimes fathers) struggle to maintain a comfortable relationship with adult daughters living on their own.

Traditionally, sitcoms have focused on the mothering of pre-adolescent and adolescent children like Bess Lindstrom. They need weekly discipline and lessons reiterating the difference between right and wrong. But what happens to those relationships when the children grow up? Sitcoms have tended not to deal with this except through distorted, atypical circumstances like the domineering-mother-next-door that was the plot engine for seemingly every episode of Everybody Loves Raymond. Instead, sitcoms contrive new (inevitably shark-jumping) plotlines that will re-set the cycle of precocious children growing up under the gentle guidance of loving parents. This means that sitcom parents on the verge of becoming empty-nesters must brace themselves for a return to child rearing thanks to middle-aged pregnancy (Family Ties and Growing Pains). If not that, they become guardians to orphans (The Donna Reed Show) or grandchildren/ step-grandchildren (The Cosby Show). Narratively speaking, these relationships are so appealing because of the stark imbalance between the parents’ maturity and the child’s immaturity. From this dynamic it is easy to wring sitcoms’ favored brand of light didacticism.

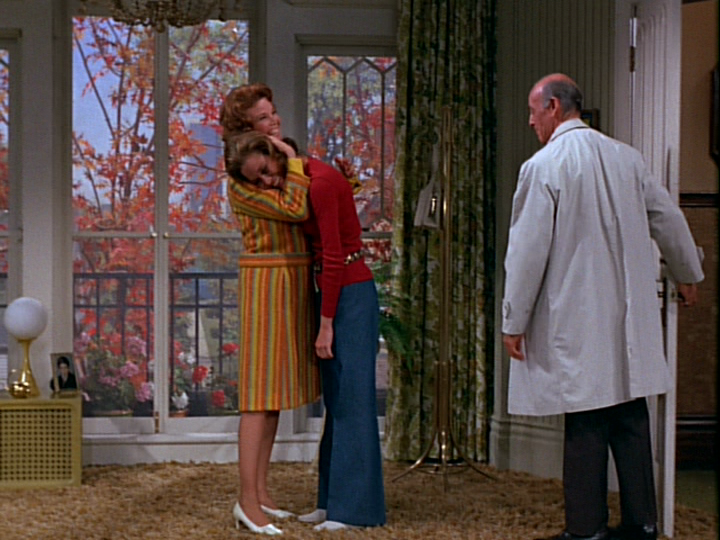

Mary Tyler Moore, however, operates from a more complex premise in which the children—Mary and Rhoda—are well-adjusted, self-sufficient adults. In effect, when it comes to maturity, they are their parents’ equals. Despite this, these relationships are messy in ways that offer no simple solutions and call into question Mary and Rhoda’s autonomy. “Just Around the Corner” (Season 3, Episode 7), the episode famous for revealing that “good girl” Mary has an active sex life despite her singleness, forces Mary to confront the fact that she still occupies a liminal—to borrow a pet word in academic discourse—space. She is financially stable. She is a valued employee and beloved by her coworkers. She has a host of supportive friends. As her knowing comments in “You’ve Got a Friend” (Season 3, Episode 11) about Ed, the sportscaster who clearly expects sexual favors in exchange for baseball tickets, prove, she knows how to read men. In other words, her parents have no logical reason to be concerned, yet when they move to Minneapolis, they treat her as an adolescent. Mary’s father may be the one who keeps checking on her with his early morning phone calls, but it is Mary’s mother who struggles to find a way to relate to her unconventional daughter. At first, she repeatedly emphasizes her own relative youth, seemingly in hopes of establishing a kind of sisterly bond with Mary. “A Girl’s Best Mother Is Not Her Friend” (Season 2, Episode 5) later rejects mothers and daughters as sisters/friends in part by having Ida Morganstern appear ridiculous for wearing clothes identical to Rhoda’s because “it’s nice.” One could argue that Dottie Richards is envious of Mary and believes she could pass as a single career woman herself. Standing in Mary’s apartment, she says she wants “a place just like this.” That strategy, though, is short-lived, and she reverts to being an embarrassingly hands-on mother prone to awkward hugs. She insists on renting an apartment in Mary’s neighborhood, fusses with Mary’s hair before she goes out, and reminds her not to stay out too late on a work night. She uses a meatloaf she’s made for Mary as an excuse to get into her daughter’s apartment when she isn’t home. She admits to Mary she does these things because “I like you,” but she lacks the ability to translate that liking into a satisfying relationship for both mother and daughter. Her smothering actions are a product of her anxieties: she wants to maintain a close connection to Mary, but their relationship seems to lack a comfortable context.

What goes unspoken is that Mary’s mother treats her like a child because she cannot treat her as a wife and mother, the ways she “should” be traditionally treated as a woman over thirty. In fact, this is apparently a longstanding, latent issue between Mary and her parents because when Rhoda asks her if they ever bring up the fact she is not married, Mary says, “not directly.” (For Rhoda, things are not so obscured. Her mother, she says, “holds a grudge” against her because she is not a housewife.) The episode implies that Mary’s life choices do not meet with the greatest resistance in the public sphere of work where the more groundbreaking attributes of the series reside, but in the private sphere of family. When it comes to Mary’s parents, and Rhoda’s, too, being a wife and mother are the silent prerequisites for accepting their daughter as fully adult. Rhoda experiences the same over-protectiveness. Every time she moved in the Bronx, her parents moved too, and her mother makes regular visits to Minneapolis to monitor her husband-hunting progress.

The inherent vulnerability that comes from being a woman in a world full of predatory Eds is at the heart of the matter. When Mary laments feeling as if she has to call her parents if she is going to be late, I recognize my own frustrations. I make these same calls myself out of a combination of respect and consideration. It pains me to imagine my own parents worrying because I know that for them, like Mary’s parents, lateness equals danger, the hostilities of the world unleashed on an unprotected woman. However, I resent them as Mary does because they challenge my otherwise deep, inarticulable affection for my parents. Despite my mother relaying her displeasure at an acquaintance asking how I cope with not being married as if I have a disease, I often think while dialing, I wouldn’t have to make this call if I was. If Mary and Rhoda had husbands, their mothers would not be so oppressively attentive. A husband would stand in the gap between them and the world and shield them from harm. He would be constant, reliable, chivalrous. Put simply, a husband would relieve them of their parental duties. Moreover, without husbands, they are without children, denying Dottie and Ida the ability to communicate with their daughters as fellow parents. Surprisingly, this fact is revealed through Lou Grant in “You’ve Got a Friend.” He has no trouble sustaining lengthy conversations with his daughters because they share one inexhaustible subject: his grandchildren.

Nearly fifty years after its premiere, Mary Tyler Moore still illuminates truths about womanhood. The easy response would be to express anger at such apparent stasis. What I find remarkable is that it not only acknowledges the messiness of motherhood and daughterhood but doesn’t bow to sitcom conventions in doing so. “Just Around the Corner” ends with Mary standing her ground, unapologetically refusing to share details of her personal life with her parents. Her chastened mother appears to have learned the lesson that Mary does not owe them an explanation, a fact she and Mary’s father will have to get used to. Just as a tidy sense of resolution sets in, she adds, “We’ll never get used to that.” Family harmony is not restored according to sitcom convention. The tension lingers, masked by Nanette Fabray’s comically resigned reading of the last line. While offering little in the way of hope and reassurance, it offers something better, something beautifully yet frustratingly real.

Image Credits:

1. Mary Richards and her mother, Dottie Richards (author’s screen grab)

2. Rhoda and her mother in matching outfits (author’s screen grab)

3. Dottie Richards, “We’ll never get used to that.” (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.