Can you imagine Mary Richards as a radical queer?

Gerald Walton / Lakehead University

I have a bone to pick with Mary Richards. [1]

It is not that I did not love The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Forty years after its finale, I still do, often binging on the DVDs. The show was, and continues to be, acclaimed as a milestone in feminist-representations on American network comedy television and a showcase for women’s equality and agency beyond the home.

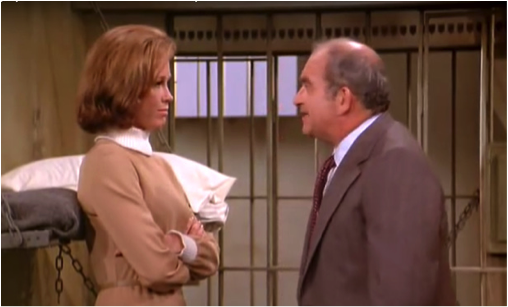

Not only was The Mary Tyler Moore Show a beacon of modern White feminism, it was also hailed for its inclusion of contemporary, liberal ideals. For instance, Mary Richards was also a small screen gay icon. A 1973 episode featured a gay character, one of the first television shows to do so that did not pander to homophobic stereotypes and swishy mockery for cheap laughs. The politics of depicting a gay man in a respectful and multi-dimensional way on network television was beyond my grasp, given that I was 9 years old at the time of broadcast and not knowing what a “gay icon” was in the first place or even that I was gay myself. As significant as that moment was in the history of queerness in American pop culture, her being a gay icon involved more.

For me, The Mary Tyler Moore Show was a refuge from the loneliness and torment of my exile from other boys my age. I was not rough-and-tumble, aggressive, or, as it turned out, sexually interested in girls. Ultimately, I came to see Mary Richards as a role model for women, yes, but also as hope for “failed” boys like myself. She would have championed and protected failed boys rather than tormented and further alienated us.

She was resilient but timid, self-effacing, socially-conscious. If Mary could be emboldened to make it on her own, perhaps we could, too. Like Mary, I wanted my own apartment, enjoying both friends in my building and friends at work. I wanted to be Mary Richards. Though it may be a gay cliché, yearning to be Mary was about more than her fabulous apartment and impeccable fashion sense, although of course that was part of it; after all, young queerling boys tend to respond positively to aesthetics. Beyond surface appearances, what resonated so deeply was her insistence that she not be secondary to men in any context. It was her ability, even with trademark hesitation, to go head-to-head with men for the sake of her dignity as a woman pursuing a career.

There were, of course, other female sitcom leads in network television. Lucy, for instance, was a Chaplinesque clown with impeccable comedic timing, Maude was a caustic, liberated woman who was a verbal bulldozer when she needed to be, and Roseanne was crude and uneducated, but took the risk of standing up for social justice as a working-class mom. Lucille Ball, Beatrice Arthur, and Roseanne Barr, respectively, were unique by virtue of the fact that most sitcoms were headlined by men. They were determined and ambitious but, especially in the case of the latter two, they were also scorned by men and women alike for being, unlike Mary, too brash, too loud, too political, too in-your-face. In them, however, some women, and even some men, found role models that gave them inspiration and hope for agency, a life on their terms.

Mary Richards represented such agency, but in a more conservative way than Maude and Roseanne did, and in a less zany way than Lucy did. In Mary Richards, failed boys witnessed possibilities for finding a place where we belonged, where we could stand up for ourselves, where we could call some of the shots and determine who we were and what we wanted to be even if other men stood in our way. Mary could goof things up and still be loved by her friends. She made mistakes. Such vulnerability was comically depicted in an episode that could have been entitled “Bad Hair Day.” Despite her foibles, she was not the target of ongoing bullying that attacked her deeply and personally on the basis of her gender. The fictional world of Mary Richards is where failed boys could find solace. Some of us saw in Mary what we yearned to be in real life.

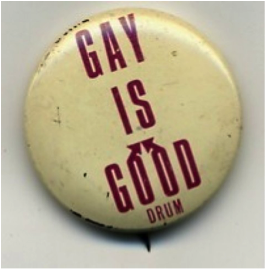

In the days after Moore’s death on January 25, 2017, columnist and radio host Colin McEnroe described Mary Richards as “just one of us,” meaning everyday folks. But fitting in as “just one of us” has dangerous implications. Fundamentally, Mary represented respectability, which is certainly one of the reasons The Mary Tyler Moore Show was such a hit. Across queer communities, Mary’s approach to finding her place in the world mirrors conservative gays and lesbians who do their best to appeal to the majority by saying in behavior and demeanor, if not actual speech, “We’re like you, straight people, so there is nothing to fear from us.” Liberal gay politics emerged from the gay civil rights uprising of the late 1960s and 1970s. In those early years, “gay is good” was the adage that sought to build equality with straight people. [2] Although the phrase is an artefact of that particular social and political time, [3] the ideology of sameness = equality pervaded later queer rights campaigns, most notably marriage equality. The position that “We’re not different from you, so we deserve the same rights under the law” had, and continues to have, political currency, largely because many queer people want to be included as “just one of us” and many straight people do not feel threatened by the logic of sameness. The result is that queers have become mainstream. We are out and proud, have supportive families and co-workers, and deserve equal rights under the law with straights.

I now see Mary Richards through older, more politically mature eyes. As much as she was a beacon of feminism, hers was a White liberal version. Mary sought to fit in and slowly work towards change, from the inside. She was not out to rock the boat, even when she landed herself in jail for not revealing a journalistic source. Being socially conservative and caring about what others thought of her, and being able to understand a reasonable argument, Mary Richards would have supported marriage equality if The Mary Tyler Moore Show were in production today instead of the 1970s. She might not have comprehended flamboyant drag queens of colour, radical faeries, bull dykes, gender-fuckers, or other marginalized groups within the broad spectrum of queer communities. Such marginalized queers were the ones who truly rocked the boat, most famously sparking the Stonewall riots of 1969, one year before the debut of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. The riots were about revolution and refusal to be pushed around by the cops who made raiding bars and hauling queers to jail a routine. The queers who fought back were unconcerned with respectability. They were angry and visceral. [4] Their uprising against the cops, and society broadly, was a foreshadowing of the now-hackneyed jingle, “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” that Queer Nation made famous two decades later. [5] Fighting back was a refusal to gain a place at the table by capitulating to the politics of sameness.

Respectability is where I, as a 50-something gay man, depart company with Mary Richards. Pandering to respectability through campaigns of marriage equality is fine. It is our right to say “no” to marriage rather than having the state do it for us. But I do not trust the politics of sameness on which equality with straights is built. In the 1970s, I did not feel the same as other boys. I was different from them. I was treated like shit because of it, as those on the fringes usually are. The message from other boys was that I was not “just one of us,” but if I wanted to be, I had to straighten myself out under the weight of sameness. After several failed attempts to fit in, I eventually had my personal Stonewall moment and replied, “fuck you.”

I found a hero in Mary Richards when I was young, and I continue to celebrate The Mary Tyler Moore Show today. Yet, I can now see the political limitations of Mary Richards. Respectability might result in fitting in, but it also goes hand-in-hand with the regime of sameness that marginalizes unconventional queers.

Image Credits:

1. Mary Tyler Moore as Mary Richards in The Mary Tyler Moore Show

2. Phyllis introduces her brother Ben to Mary in the 1973 episode, “My Brother’s Keeper”

3. In the late 1960s, “gay is good” was the adage that sought to build equality with straight people

4. Mary Richards represented a feminism that was never out to rock the boat

Please feel free to comment.

- With thanks to Aaron Wilson and Özlem Sensoy for helpful feedback. [↩]

- Capehart, J. (2011, October 12). Frank Kameny: American Hero. Washington Post . [↩]

- The adage also followed the “Black is Beautiful” motto of the 1960s Black cultural movement, a significant component of the Civil Rights movements. [↩]

- The 2015 film, Stonewall, was widely criticized for its focus on white, attractive, male, middle-class gay young men rather than on marginalized queers who were the actual epicenter of the uprising. [↩]

- Retrieved from http://queernationny.org/history. [↩]

this is the thing that all need for us.