Make Room for Alexa

Germaine Halegoua / University of Kansas

The Consumer Electronics Show (CES) held its annual tradeshow last weekend. Reports from the “smart home” front heralded 2017 as the year of where voice and gestures will control Internet-connected household appliances, robots, and artificial intelligent agents. Whirlpool, and an extensive list of other companies, showcased prototypes and devices that interact with the Amazon Echo’s voice-controlled, digital personal assistant, Alexa. Journalists declared that that Alexa was “everywhere” and that “we’ve seen the future and it’s Alexa enabled.” Although there are other smart home systems on the market including Google Home, ivee, Apple HomeKit, and Athom Homey, at present, the connected home seems to be connected to Amazon. In approximately 5.1 million living rooms, kitchens, and bedrooms across the United States people have made room for Alexa.

Previous media studies scholarship has attended to the culture and architecture of domestic spaces where television, radio, desktop computers, mobile devices, or other electronic media or audio/visual/digital technologies are installed and engaged. Television, radio, telephony, and the Internet have all been regarded as “windows on the world,” which blur public and private space and re-organize participation in everyday life. [1] The voice activated smart home console that ruled CES this year is also a “window” or portal to the world. But what kind of screen-less window is this? How do users make sense of and make room for intelligent agents like Alexa within quotidian, domestic spaces and activities? And what type of interaction and engagement with the world, and with each other, do these responsive information managers present?

The advertised intelligence of the smart home is reminiscent to that of the smart city – domestic space is enhanced with Internet connected sensors, cameras, and digital devices that recreate the home as a sentient, predictive, and responsive environment. Smart home devices remember, anticipate, or respond to residents’ requests and preferences in the service of efficiency, safety, convenience, and/or sustainability. Like the smart city, most smart homes are retrofitted to be smart. The average middle or upper middle-class home is never entirely smart like the Gates’ House, Slow House, Wired Home, or luxury homes of tomorrow. More frequently, a household will have piecemeal Internet of Things technologies, or a few networked appliances or “accessories” that render the home “smarter.” The convergence of various smart accessories like lighting systems, thermostats, refrigerators, water leak detectors, security cameras, music and media systems tend to be coordinated by central concierge services controlled by residents. The Amazon Echo and Google Home are two of these convergent, intelligent agents.

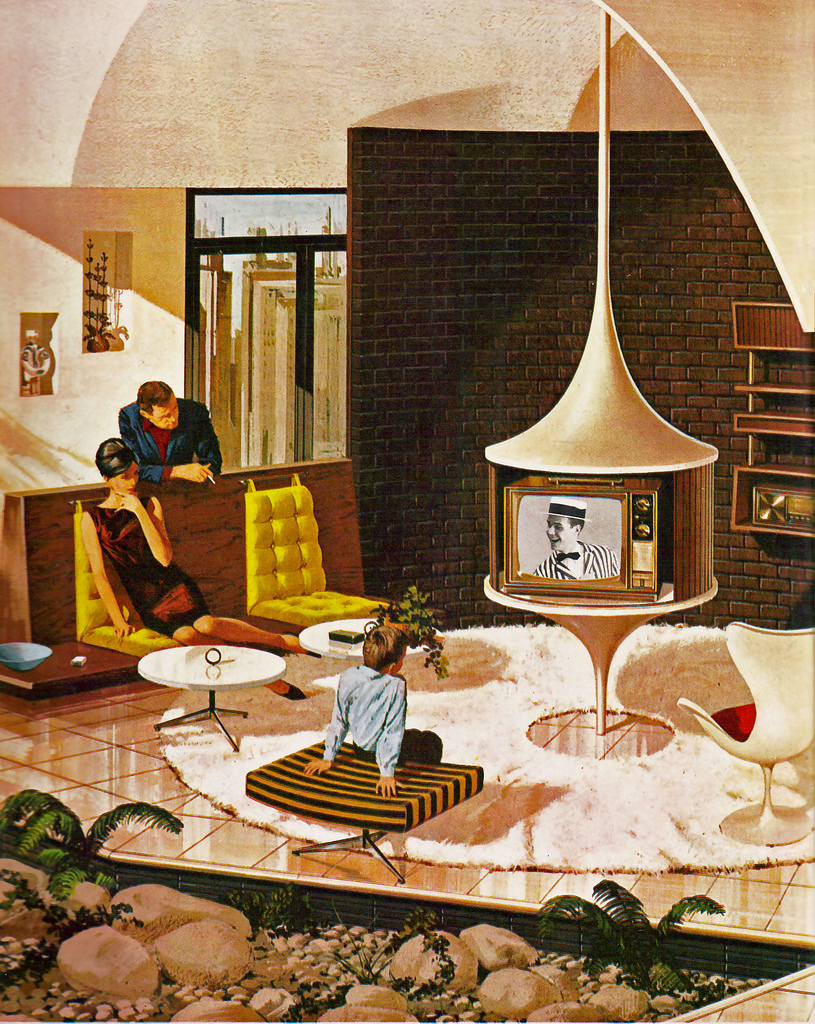

As Lynn Spigel and others have contended, media “homes of tomorrow” are built on negotiating or highlighting incompatible binaries which might include: public and private, mobility and sedentariness, future and nostalgia, innovation and familiarity, liberation and control. For example, Spigel notes that 1990s visions of smart homes imagine residents who “have it both ways” – “domestic comfort and stability” as well as “futuristic fantasy of liberation and escape.” [2] Spigel’s research on the media home emphasized these binaries within new forms of theatricality and spectatorship in middle class domestic spaces and emerging forms of ambient and active audiences of screens (televisions, video walls, control panels, visual ubiquitous computing interfaces). Smart homes present additional binaries to be negotiated: visible and invisible, presence and absence, transgression and maintenance, interaction and distance.

New media homes maintain these concepts of theatricality, mobility, and sentience in the form of sensors and monitors rather than screens — through listening rather than seeing. Virtual assistants like Alexa represent a shift from the imagination of the smart home as a space of ambient screens to ambient interfaces for continual background listening. The living room is still a stage but the theatricality of the televisual home shifts from home theater to an interactive performance, a play of call and response between human, machine, and information. Spectators watch Alexa, a calm, disembodied, feminine voice housed in a cylindrical encasement, complete requested tasks and tricks.

While some ambient interfaces are designed to be invisible or remain unnoticed, Google Home and Amazon Echo are the opposite, they’re personified and emphasize a desire to be heard and responded to. Although these devices are “always listening” in the background, the user “wakes” the device through direct address, calling it by name. Customers in unboxing videos, reviews and comments, and discussion forums commonly anthropomorphize the Echo and refer to Alexa as “she” and “her.” People comment on the Echo or Google Home’s look, weight, measurements, and design as if they were referring to a body. The gendered devices are given voice but are expected to serve their users and speak only when spoken to.

Amazon’s advertisements for Alexa depict households where stereotypical domestic roles are upheld. Women are shown using Alexa in the kitchen while cooking or caring for children, while men are heard ordering Alexa to buy roses for their partner instead of the dinner or cake they attempted to bake. Men are shown to treat Alexa as a concierge or personal assistant and utilize app and remote functionality to control environments at a distance (turn on lighting fixtures or lower speaker volume). Comments and blog posts by women discursively construct Alexa as a companion, a member of the household, or even a best friend. Even Alexa’s transgressions and unruliness are gendered. When Alexa “goes rogue,” she tends to buy merchandise (presumably from Amazon.com) or maybe “goes wild.”

In one promotional video introducing Amazon’s Echo, a suburban family lounges around Alexa with the fireplace at their backs. Directing their attention to the console, watching it work and waiting for curated information to be brought into the home. Mobile privatization or privatized mobility works differently in new media smart homes. Travel outside the home is optimized or made more efficient by setting alarms and alerts, providing up to date information about weather, traffic, or creating automatic to do lists. Unlike the portable radio, the Echo’s cord prevents mobility outside of the home, and unlike the home theater Alexa’s responses do not necessarily transport residents somewhere else. Instead, Alexa offers the mobile privatization of the world instead of the subject or audience member. Goods and services are packaged or ordered and sent to your door, the delivery of encyclopedic amounts of information is not a click, but a question away. The Echo doesn’t promise to take us where we need to go, but bring what we need, or at least what we ask for, to us. Although smart home accessories rely on high-speed connectivity, motion-activated sensors, and the anticipation of activity and alerts, the consoles that control and manage these devices belie the smart home as far more ambient than active. Unlike past “homes of tomorrow” it’s the feminine voice of an on-call background listener, rather than the lights and sounds of a simulation screen that invites us to sit back, stay in our place, and just stay home.

Image Credits:

1. The Amazon Echo

2. A media home as envisioned by Motorola.

3. A Samsung booth at a consumer electronics show in 2013 displays smart home technologies.

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Fart Jokes, Pranks, Selfies and Other Applications of Smart Technologies Germaine R Halegoua / University of Kansas – Flow