Shake My Turban: Alter Egos and Altering Perceptions in Trump’s America

Suzanne Enzerink / Brown University

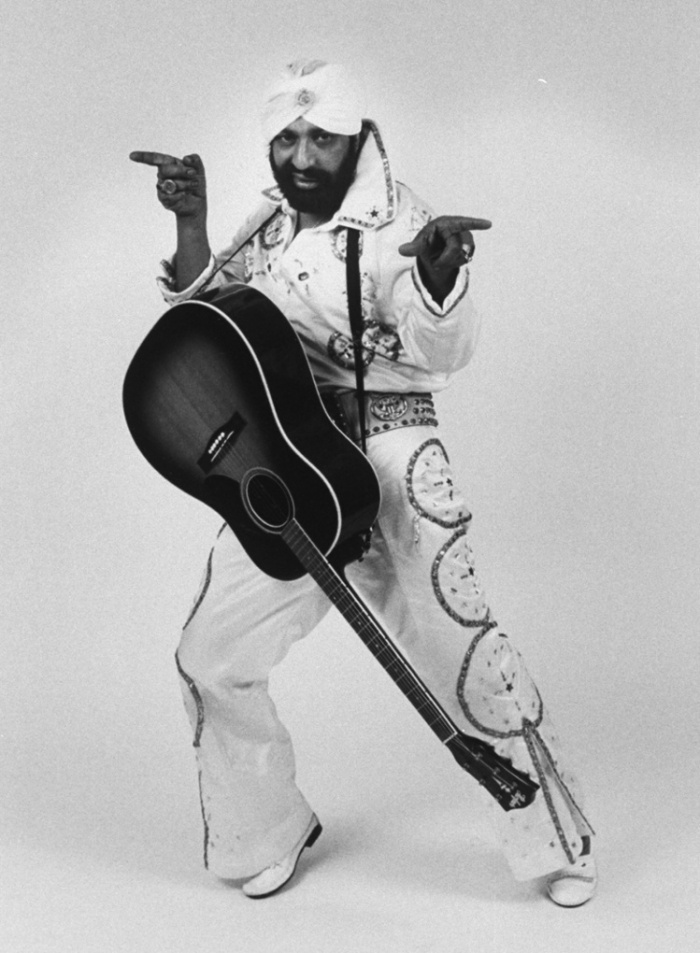

In the midst of this year’s election season, a 1986 short documentary called Rockin’ with a Sikh resurfaced on social media. The twenty-six minute profile starred Peter Singh, an Indian-born Sikh who ran a hybrid curry/English takeaway restaurant in Swansea, England, by day, and transformed into a Sikh Elvis at night. With songs like “Turbans over Memphis” and “Who’s Sari Now,” Singh modeled that being a devout Sikh and idolizing mainstream American pop cultural icons were not mutually exclusive—in addition to the turban, Mr. Singh sported a full beard in adherence to kesh, one of the five outward manifestations of Sikhism, the practice of allowing hair to grow naturally. “I don’t smoke dope/ I don’t drink Bourbon/ All I want to do/ is shake my turban” became Mr. Singh’s most popular catchphrase, garnering him a cult following that remains to this day. Sikh Elvis was a positive enunciation of a Britain that was globally-oriented and could embody difference without demanding full assimilation. It was a facile multiculturalism, in a way, one able to celebrate ethnic difference superficially whilst ignoring the racism that already permeated Britain and the U.S. in the 1980s— “Everyone especially loves my spicy food. I wish Elvis could taste my spicy foods. I’m sure he would love the papadums,” Singh said for example—but the move remains powerful, symbolically accommodating both religion and popular culture, the national and the global, rather than casting these metrics as in tension.

Fast forward to 2016, and these tensions have yet to be resolved definitively. Large segments of the population still need to be reminded that being an American and being a Sikh — or a Muslim, a Buddhist, a Hindu, etc., for that matter — are not mutually exclusive or oppositional identities. They are, in fact, wholly compatible, yet the vitriol aimed at Captain Khizr Khan’s family by Donald Trump and his supporters readily demonstrates that the potent mix of Islamophobia and Anglo-Christian entitlement still produces a highly exclusionary idea of who can lay claim to the label of “American.” Tangled up in this is an injurious stereotyping of Muslim and Muslim-perceived Americans as terrorists, circulated widely in cultural productions in the aftermath of 9/11. Members of this group are guilty until proven innocent: Donald Trump’s proposed registry and loyalty test are the most blatantly Islamophobic incarnation of this, yet even Hillary Clinton’s suggestion that we need “American Muslims to be part of our eyes and ears” and “part of our Homeland Security” dangerously fuses patriotism with surveillance. As Jasbir Puar and Amit Rai note in their study of how contemporary media has constructed the South Asian, the turban works to “produce the terrorist and the patriot in one body, the turbaned body.”[1] It is through excessive nationalism and self-surveillance that the turbaned subject must seek to redeem itself, but always in vain within this exclusionary white vision of America.

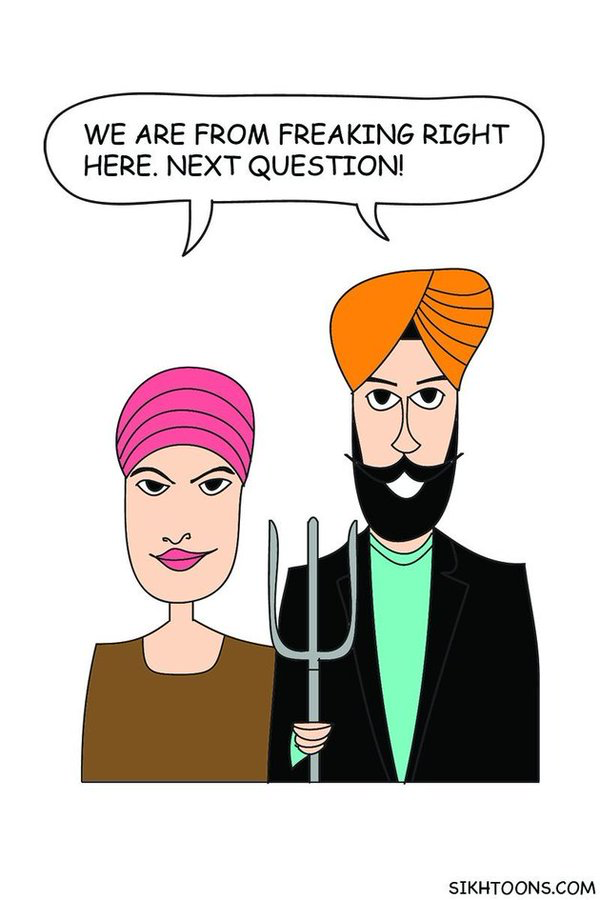

What could be a more powerful critique, then, than taking one of the nation’s dearest and most widely-circulated characters, the very embodiment of American values, as a way of challenging this wounding and decentering its monolithic whiteness? The most compelling and viral challenge to white nationalist definitions of Americanness during this election season came in the form of a beloved American hero, Captain America. Like Sikh Elvis, the iconicity of Captain America lends itself perfectly to show that the idea of Brits or Americans as white males was always a fiction, and an increasingly fantastical one. Sikh Captain America, the alter ego of Vishavjit Singh, a cartoonist from Washington, wears the classic star-spangled costume with a turban, an “A” boldly emblazoned on it. His cartoons—or Sikhtoons—challenge the rhetoric of fear espoused by Trump, the myth of the perpetual foreigner, and misconceptions about turbans, all crucial elements that render Sikh and Muslim Americans “suspect” in the eyes of many Trump supporters.

The former are especially vulnerable, as their turbans made them targets for profiling even before 9/11. Sikh Captain America’s role reversal, from terrorist to hero, then powerfully resonated. #sikthoons trended on social media, and sources like Slate, The Washington Post, and The Huffington Post covered Singh during the primaries, and during his trip to the Republican National Convention. With Trump in office, he feels his mission more urgently than ever; his presence is more needed than ever to counter the overt racist displays circulating widely.

Social media propelled Sikh Captain America to fame, but with its relative lack of oversight and lightning quick dissemination, it has also been one of the main outlets for perpetuating stereotypes. After the attacks in Nice, a photoshopped selfie of a Sikh Canadian man named Veerender Jubbal was circulated identifying him as an “Islamic terrorist.” The same thing had happened to Jubbal after the 2015 Paris attacks. Only by bringing into circulation competing narratives, and challenging who gets to define what America(n) is, the turbaned terrorist will begin to erode as the dominant image. By giving the turban positive visibility, Sikh Captain America is simultaneously educating Americans and debunking racist associations.

He is not fighting alone. Actor Riz Ahmed and Heems of rap duo Swet Shop Boys also tackle profiling, both lyrically and visually. Their 2016 song, “T5,” tongue-in-cheek remarks that they “always get a random check when [rocking] the stubble,” highlighting again that hairstyles can impact how others read us racially or ethnically, and how they attempt to glean our political leanings from such readings. The visual work of Sikh Captain America, the uncoupling of the beard and turban with terrorism and coupling it instead with patriotism, thus has direct effects.

The trope of the terrorist is not unique to the United States, and the Swet Shop Boys also ask us to consider how stereotypes travel. Ahmed is British Pakistani, Heems is Indian American. In “T5,” they reference newly-elected London mayor Saadiq Khan as a positive model while simultaneously disparaging Trump. The video opens with audio describing Trump’s proposed “loyalty test” for Muslims, while Riz MC later raps that “Donald Trump wants my exit, but if he press the red button to watch Netflix, bruv, I’m on.” The South Asian diaspora is equally affected by xenophobic impulses, not confined to national borders for inspiration or protected by them from threat. The line also highlights a central irony: Americans will consume productions starring Muslim or Muslim-perceived Americans without hesitation, but this has not yet translated into shifts in thinking that can see beyond stereotype and accord them complexity, diversity, and humanity.

Certain representations complicate things, raising the specter of terrorism only to then challenge it. Scripted shows, for example, have also made efforts to stop the equation of terrorism with brownness, but more mutedly so. ABC’s Quantico, for example, resorts to hypernationalism to offset its criticisms—the FBI trainees of season 1, and CIA recruits of season 2, are willing to risk their lives to protect the safety of the United States, even if the country has conspired against them and wronged them. Priyanka Chopra’s Alex Parrish, an FBI agent of mixed Indian and American descent, is framed for a terrorist attack on Grand Central station. Yet when asked by an Anonymous-inspired group aiming to exonerate her what she would like to tell the 12 million viewers of the live broadcast, she replies: “I love this country.” Even though Alex knows that the real attacker chose her because “in this country I’m an easy person to blame,” a move that relies on an association of brownness with terrorism (as Alex says, “they framed the brown girl”), she never faults the country as a whole for its structural inequalities or racism. In the realm of Quantico, America is not to blame, but certain malevolent actors within it are. It is thus through a hypernationalism that they frame their critique, but for a primetime TV show, it is a gesture at challenging the stereotype of the brown terrorist nevertheless.

Such efforts are especially crucial to diversity and increase the representation of brown Americans who are hypervisible as terrorist stereotypes yet often marginalized when it comes to discussions of discrimination. In October, New York Times-writer Michael Luo was told to “go home to China” by a woman unknown to him on the street. In response, the Times collected and chronicled racist incidents of a similar nature via #ThisIs2016. The hashtag was so powerful—flooding Twitter for days—that The Times invited some respondents to star in a video to tell their story. None were South Asian or Filipino. Invisible again, a group of brown Americans wrote an open letter, noting that their erasure was painful as “our brown skin activates different kinds of stereotypes in this country.”

The stereotypes are generalizing and dangerous. When asked by Lt. Brian James Murphy, who was shot fifteen times by a white supremacist when he responded to calls of an ongoing massacre at a Sikh gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, how he would protect the rights of minority groups, Trump’s answer only included the need to combat “radical Islamic terror.” Even Murphy’s remark that 99% of turban-wearing men in the United States are Sikh and not Muslim, was cast aside by Trump. Muslim or Muslim-perceived, American or not, right-wing media and candidates make all of them potential terrorists. The first victim of the last spike in hate crimes in the U.S before Trump., in the aftermath of 9/11, was not coincidentally also a Sikh—Balbir Singh Sodhi, a gas station owner, was killed on September 15 by a man on a mission to shoot “some towelheads” in retaliation for the attacks.

Caught between such spectacular misrepresentation and invisibility, Sikh Captain America really is the hero these United States need, and brown Americans especially. I taught his ‘toons this semester, together with music by Swet Shop Boys. Their transnational archive highlights the interconnectedness of global crises that have seen a rise in hate crimes and increased popularity of the far right (white supremacy) across nations. It is not just Donald Trump or Steve Bannon. The global reach of contemporary media, be it social or entertainment, has provided complexity and visibility where it was lacking. It also supplements scholarly works that have dealt with the same question—by showing their prevalence in current political and media discourses, students were able to discern and dissect stereotypes constructed across genres, that powerfully and detrimentally determine how groups of people are perceived.

Twenty years after Sikh Elvis asked the Brits to embrace his turban as part of the British fabric, rather than at odds with it, #sikhtoons and #ThisIs2016 effect the same here for (South) Asian Americans—but rather than a question, it is now a demand for the full humanity that Trump and his ilk seek to deny them.

Image Credits:

1. The Sequined Sikh Elvis

2. Vishavjit Singh’s Sikhtoons

3. Quantico‘s Critique (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Jasbir K. Puar and Amit S. Rai, “The Remaking of a Model Minority: Perverse Projectiles under the Specter of (Counter)Terrorism.” Social Text 22.3 (Fall 2004): 82. [↩]