It’s the Political Economy Stupid: The Case for Media Industries Studies in an Era of Fake News

Christopher M. Cox / Georgia State University

Alex Jones describes himself as a “trailblazer of new media.” He is less apt to apply the moniker of “fake news” to his affiliated brands (such as websites InfoWars.com), even though CBS News shows less restraint – it recently counted InfoWars among fake news sites.

Fake news itself isn’t a recent phenomenon. Disingenuous information has long plagued journalistic inquiry and endured despite efforts to instantiate professionalized ethics, institutions, and training related to news reportage. These undertakings seek to curb the deleterious effects of information that has no reliable claim to empiricism yet flourishes as a means of ascertaining truth, as in the case of the recent Pizzagate conspiracy theory that identified Hillary Clinton and her 2016 presidential campaign chairman John Podesta as participants in a child sex-trafficking ring operating through Comet Ping-Pong Pizza, a Washington D.C. pizzeria.

While these claims have been thoroughly debunked by outlets ranging from The New York Times to Fox News, the widespread dissemination of this fake news led to real material consequences in the form of a gunman who entered the pizzeria with an assault rifle and fired a shot in order to “investigate the claims” made by Pizzagate adherents, including Alex Jones. Even after the incident, the shooter “refused to dismiss outright the claims.”

Indeed, much of the online commentary around fake news focuses on the need for such dismissal, particularly on the importance of developing tools for media consumers to identify fake news, dismiss the underlying claims, and seek out reliable sources. To the extent that these efforts address what constitutes fake news and what to do about it, this essay seeks to widen the lens in order to address how and why fake news originates and the motivating factors as to its inception.

With this in mind, I argue for media industries as a disciplinary and methodological framework highly adept at accounting for the underlying circumstances that shape the production, dissemination, and consumption of fake news. In what follows, I make some brief observations about fake news and suggest some ways in which media industries studies’ indebtedness to political economy paves the way for a more assured assessment of circumstances that make fake news a profitable commodity and venture, circumstances that in turn illuminate how fake news can be distinguished from reliable journalistic enterprises. To the extent that Trump’s election was an economic mandate, political economy is a necessary mandate for scholars and critics as a counterbalance to the forces that enable fake news to shape political and economic realities.

Fake News is Clickbait.

As Melissa Zimdars recently noted after her list of fake news sites received widespread online attention, “fake news is cheap to produce…and profitable.” This profitability stems from a digital ecosystem that enables clickable interaction (searches, shares, likes, etc.) to become part of a broader commodity reflective of consumer interest and therefore attractive to third-party advertisers and marketers. Content, then, is often tailored to what will garner the greatest number of clicks, whether it’s clicking on an article itself or clicking a like or share button. Even though journalistic enterprises undertake internal checks and balances to help ensure informational integrity, professional news reporting on social media competes for clicks with entities that neither internally scrutinize their content nor find themselves subject to scrutiny by the platform in question.

While professional journalism has long wrestled with a tension between profit motivation and pro-social aims, fake news encounters no such tension. In the absence of institutional values, ethics, and gatekeeping mechanisms applied internally or externally, fake news is the neoliberal dream writ large: minimal production costs and practically zero regulatory measures. In this way, economics is the most drastic distinction between journalistic enterprise and its facsimile. Nothing distinguishes the online spread of real news from fake news more than the economics on which they thrive. Tracing economic relations thus not only helps to discern between fake and trustworthy information, but also identify connections and motivations behind emergent industrial actors that have an economic stake in the promulgation of fake news.

Fake News is Vertically Integrated.

InfoWars is more than just a space for Alex Jones to exult his worldview – it’s also a storefront that sells a diverse array of products from coffee to teeth whitening gel to apparel promoting Trump. The diversity and prolificacy of products offered through InfoWars suggests a commercial enterprise undergirded by an economic structure in which mediated content is both product and promotion, a digital commodity form in its own right and a means to advertise more tangible goods.

As one example, the below video dedicates the bulk of its runtime to discussing the Pizzagate conspiracy theory, yet opens with Alex Jones himself inducing watchers to visit the InfoWars storefront. It’s also not an isolated incident, as Jones’ YouTube videos regularly promote products for sale on the InfoWars site.

On Dec. 7, 2016, the channel posted a 5-minute video dedicated to Jones promoting the InfoWarsLife brand of ingestible supplements, a line of products regularly promoted as breakaway embeds within the Alex Jones Show. The Dec. 8, 2016 show, for instance, breaks away at just over one hour to briefly roll video of InfoWarsLife products. InfoWarsLife is also promoted in the description accompanying the video, as more than 20 InfoWarsLife products are listed with accompanying links to their respective page on the InfoWars store.

The commercialization of news reportage has long troubled the institution of journalism and its critics and remains a locus for critical analysis. But whereas the economics of journalism often place commodities and their promotion at a remove from news content, the InfoWars example demonstrates no such buffer, neither between the commodification of content or commodities promoted within such content. The integration of vertical markets and associated products is therefore a critical means of assessing the motivations to develop tight relays between content and commodity and the economic drivers that make such relays a profitable venture.

Political economy is especially important when such content and commodities situate among technologies that can be gamed to replicate journalistic forms.

Fake News is Code.

Melissa Zimdars’ documentation of misleading and clickbaiting sources includes a caution against URLs that end in “.com.co,” since they are often fake versions of legitimate news sources, advice echoed by FactCheck.org in their guide to spotting fake news. URL suffixes such as “.co” are available to anyone who registers a site name not currently taken, even if a portion of that site name replicates the URL for existing news sites.

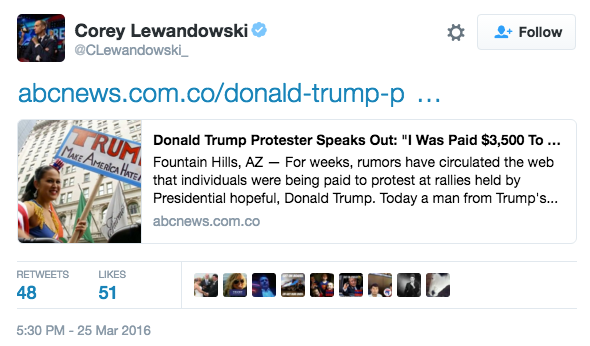

A prominent example is ABCNews.com.co, a site created by noted fake news propagator Paul Horner, who typically earns $10,000 a month in advertising sales from the uptake of his fabricated content. The site reproduces the URL, look, and form of ABC News, with only slight variations to the logo and other indicators of institutional affiliation. Its allegation that Trump protestors were paid $3,500 to protest Trump rallies caught the attention of former CNN contributor and Donald Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, who (as shown in the below screencap) spread the post via Twitter before later deleting it, but not before it found widespread purchase in the social media ecosystem.

Given that 62 percent of U.S. adults get their news from social media, the majority of news is not consumed from the source itself but from secondhand aggregators such as Facebook and Google, each of which perform algorithmic generation often agnostic to content that emanates from ABC News or ABCNews.com.co. In the wake of the election, both Facebook and Google have made gestures towards altering their technical configurations to weed out fake news, including Facebook updating the language of its Audience Network Policy to more directly account for fake news.

In their own way, they seem to be taking steps to address their role as informal regulators of aggregated content. What remains to be seen is whether or not – in the spirit of Lawrence Lessig’s admonition that “code is law” – more formal regulation is placed on entities such as domain registry services and third-party hosting services that enable fake news to mimic the URL, form, and function of legitimate news sources.

Going forward, emphasizing media industries approaches that examine the role of regulatory frameworks (both governmental and informal), in conjunction with the economic incentives that underpin digital platforms and their technological affordances, can not only cut through the complications of an increasingly nebulous media ecosystem, but offer tools to better understand relationships among various enterprises (journalistic and otherwise) increasingly bound within an expanding market of commodifiable digital forms.

What I have offered here is by no means exhaustive. It is, however, a means to underscore the fact that understanding the foundations of media industries methodologies runs parallel to the ability to understand and address deleterious effects of fake news.

Image Credits:

1. The Fake News of InfoWars

2. “Pizzagate” Moral Panic

3. Spreading the Fake News

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Special Issue of FLOW: Media Activism in/for the Age of Trump « Erkan's Field Diary

I am blown away by the depth and detail in your posts Keep up the excellent work and thank you for sharing your knowledge with us