Informational Infidelity: What Happens When the “Real” News is Considered “Fake” News, Too?

Melissa Zimdars / Merrimack College

Since the election of Donald Trump, “fake” news has turned into a widely debated topic. People are questioning whether it influenced the election, showing how some fake news articles were circulated on Facebook more than mainstream news articles, and demonstrating that the President Elect himself is prone to circulating questionable sources via twitter.

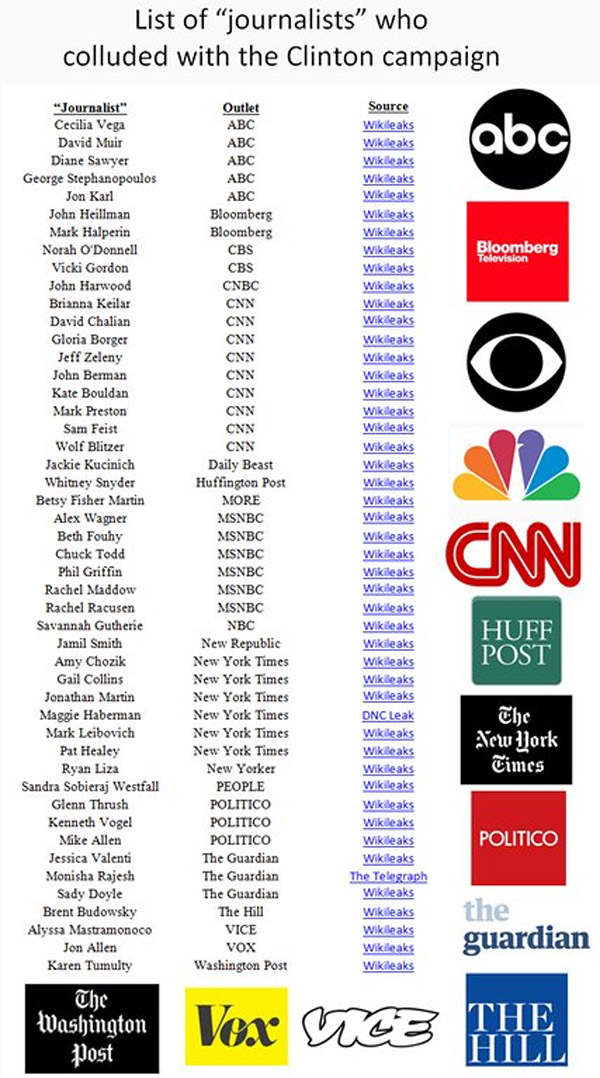

Yet after the election as numerous websites were being called out for creating outright fake news, such as 70news.wordpress.com, or criticized for circulating false, misleading, unreliable, conspiracy, or “truthy” news, such as 100percentfedup.com or Natural News, readers of those websites pushed back, arguing that mainstream news is actually the “real” “fake” news we need to be worried about (see image below). This reaction is evident in some of the push-back I received after making a resource about false, misleading, clickbait-y, and satirical ‘news’ sources, and by a man self-investigating a conspiracy theory after media outlets worked to debunk it. What can be done when media criticism and debunking just leads to accusations of either being “in cahoots” with the “lamestream media,” as was the case with my resource, or assertions that the “Pizzagate” conspiracy is a false flag staged by the mainstream media in a plot to shut down alternative media?

These accusations against mainstream news organizations as being “fake” is likely connected to studies showing a significant portion of the population distrusts “The Media.” And while claims that mainstream news organizations are the “real” “fake” news are unwarranted, the general distrust felt by many people is justifiable. During the presidential election, news organizations were criticized for giving Donald Trump too much “free air time,” for creating a false balance or false equivalence between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, and for circulating sensational headlines and stories. For example, just weeks before the election, news headlines stated that the FBI was “reopening” an investigation into Hillary Clinton’s email server following FBI Director James Comey’s statement to congress saying they were reviewing some emails potentially connected to the case in order to determine their (in)significance. Nowhere in Comey’s statement did it say Clinton’s case was being reopened, but that’s the message millions of people heard thanks to contemporary journalism. In my most cynical moments, cases like these do make me feel like “real” news is indeed “fake” news, too.

Of course “fake news” has existed as long as “real” news, with yellow journalism, tabloids, and a long history of news and magazine hoaxes inherently connected to news as an historic reality. The difference today, perhaps, is the speed of sharing all kinds of “news,” with some evidence suggesting many of us share or retweet without actually reading what we are sharing or retweeting. [1] This immediacy is mirrored in how news itself is produced, whether fake or real. Obviously, outright fake news is quick to produce because there are no interviews, investigations, or fact-checks to do. But with dwindling real news budgets and the pressures of immediacy, many news organizations also seem to be eschewing interviews, investigations, and fact checks in favor of reliance on secondary reporting. The problem with secondary reporting in the contemporary era is that news has become like a game of telephone: facts, details, and contexts change as the information quickly migrates across the web and moves further and further away from its original source.

Like fake news, secondary reporting is not a new phenomenon, with national and local news organizations long dependent on newswires like the Associated Press and Reuters to make up for shrinking staffs and smaller budgets. Now, however, instead of writing a story based on verified information (albeit information still subject to selection and framing), journalists are pressured to write stories based on virality and sensationalism, and the speed to post to social media seems to matter more than the integrity of the story itself, especially if a news organization is struggling to turn a profit.

Comedian Jon Stewart recently referred to this in an interview as “information laundering,” or how unverified, fake, and misleading sources enter into the mainstream via second-hand reporting. Adam Klein (2012), who developed this theory, argues that information laundering is similar to how criminals launder illegal funds into financial institutions. He looks at how hate-based information spreads throughout networks and search engines until it is “washed virtually ‘clean.’” According to Klein, as this “extremist content,” designed to appear as educational, political, scientific, and spiritual, circulates it becomes legitimized in mainstream spaces of public discourse. [2] Beyond the propaganda of hate-groups, information laundering is useful for thinking about how fake, hoax, conspiracy, misleading, and all other kinds of “truthy” news become disconnected from their sources, how they’re taken up by mainstream news and entertainment sites, and why they play an increasingly prominent role in our infosphere.

However, information laundering doesn’t capture the entirety of the contemporary fake news problem: real news is a problem, too. News reporting as a game of telephone, which I discussed earlier, can be thought of as “information infidelity,” or the process of inaccurately or imprecisely copying, reproducing, and/or relaying information that may already be based on questionable or unreliable sources. For example, on November 25th, The Independent wrote a story (now changed) that CNN accidentally aired thirty minutes of pornography in the Boston television market instead of Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown. Other news and entertainment websites picked up the story, including but not limited to Mashable, The New York Post, The Daily Mail, Esquire, Variety, Forbes, Maxim, and even Fox25 in Boston (most of these articles are also now changed). Did any of these organizations work to verify the claims of the original story before– sometimes inaccurately– reproducing and relaying the information? Or did they cross their fingers and hope The Independent did its due diligence? Furthermore, why did a Boston TV station rely on a U.K. publication for a story happening in its own backyard?

Shortly after the story spread across social media, CNN and RCN (the “hacked” cable provider in question) released statements denying the situation ever happened. So, where did the original information come from? Two tweets! (see images below). As noted above, many of the entities reporting on the situation quickly updated their stories to reflect the new Twitter-based hoax reality, but corresponding social media posts weren’t necessarily updated, too. For instance, image 3 is screenshot I took of Vulture’s social media post just before noon on November 26th. The headline reads, “Boston CNN Channel Airs Porn Instead of Anthony Bourdain,” and is accompanied by the description, “Shocking Viewers Who’d Forgotten People Watch Porn on Their TVs.” Already, we have an informational leap from a single “viewer” who tweeted to viewers plural. The social media post linked to an already updated story with a different headline, “Conflicting Reports Suggest Boston CNN Channel Probably Didn’t Air Porn Instead of Anthony Bourdain” (although the headline should probably read “CNN Didn’t Air Porn. We Were Wrong.”). Since around 40 percent of adults get their “news” from social media, and there is the potential for people to share “news” without reading it, social media headlines and descriptions carry enormous informative weight. This particular example of information infidelity, and lack of social media updates to revised stories, may not be a big deal, but it is a big deal when headlines, social media descriptions, and stories inform decisions on who should be the next president.

Another example of information infidelity can be found in news reports of my own viral teaching resource. The Los Angeles Times and New York Magazine wrote stories about my resource without contacting me for context (although both did as the story developed). They referred to it as a “fake news list” (since updated) despite the resource containing a variety of sources ranging from outright fake news to credible news sources that sometimes use clickbait-y headlines. When other news organizations picked up the story, using previous stories as their primary sources (not just the two listed above), some of them started referring to my resource as a “hit list” or a “blacklist,” which is definitely not what I created. Thus, my resource took on a life of its own as imprecise information lead to further inaccuracy as the story was copied and reproduced across numerous news and entertainment websites. On the bright side: due to information infidelity, I somehow managed in these news reports to receive a promotion to Associate Professor in my second year as an Assistant Professor.

As has become all too clear, even reputable news organizations and media entities now report on google docs, tweets, and blogs without necessarily digging into their credibility, and then other news organizations and media entities report on those stories which were based on google docs, tweets, and blogs (assuming the original stories to be accurate). This kind of information infidelity, and other practices plaguing contemporary news and “news” media, feeds not only public distrust of mainstream news organizations, and of information generally, but also gives support to accusations that the “real” news is actually “fake” news, too.

Right now, journalists are blaming fake, false, and otherwise misleading “news” sources for the political misinformation circulating during the election, while think pieces ponder whether we now live in a post-Truth world, but just as the emergence of Donald Trump can be explained by practices within the GOP, fake news can be explained, at least partially, by these practices within contemporary journalism. So, while we think about fake news, actual news organizations need to start proving to all of us that we wouldn’t be better off by replacing them with a 24-hour Taylor Swift Channel.

Image Credits:

1. Information infidelity further blurs the line between “fake” and “real” news.

2. Website readers argued mainstream news is the “real” “fake” news.

3. An example of “information infidelity” spurred by a few stray tweets.

Please feel free to comment.

- Maksym, Gabrielkov, Arthi Ramachandran, Augustin Chaintreau, Arnaud Legout. “Social Clicks: What and Who Gets Red on Twitter?” ACM SIGMETRICS/IFIP Performance Conference, June 2016, Antibes Juan-les-Pins, France. [↩]

- Klein, Adam. “Slipping Racism into the Mainstream: A Theory of Information Laundering. ” Communication Theory 22, 2012, pp. 427-448. [↩]

Pingback: Special Issue of FLOW: Media Activism in/for the Age of Trump « Erkan's Field Diary

Pingback: Információs hiteltelenség, avagy hogyan válnak a valós hírek valótlanná – máshol