The Scourge of Fake News

Richard Van Heertum / New York Film Academy

In the wake of a party-changing presidential election or collective traumatic event, there is a tendency for bold proclamations of a sea change in the cultural milieu. In recent history, there are two rather profound examples, the short-lived incantations of a “post-ironic” age after 9/11 [1] and the rather absurd “post-racial America” discourse that followed the victory of Obama in 2008. [2] With the election of Donald Trump last month, a new narrative has developed, proclaiming a “post-truth” world, where fact and fiction are indistinguishable and “fake news” has sullied the public sphere beyond recognition. [3]

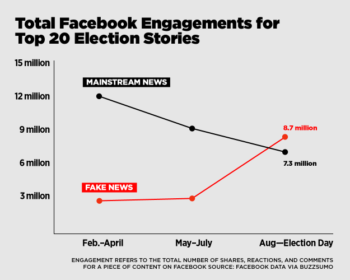

Unlike the stories of a post-ironic or post-racial age, there appears to be less hyperbole in the more recent arguments around the inception of a “post-fact” America. In fact, there is growing empirical evidence to support these claims. One such source was BuzzFeed, which showed that fake news stories on Facebook, in some cases passed along by Russian hackers, may have fooled a rather large percentage of the electorate into voting for a man who does not appear to have their best interests at heart. They found that during the final, critical months of the campaign, 20 top-performing false election stories from hoax sites and hyperpartisan blogs generated 8,711,000 shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook, compared with 7,367,000 shares, reactions, and comments for the top 19 articles from reputable sources. [4]

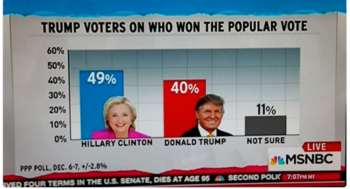

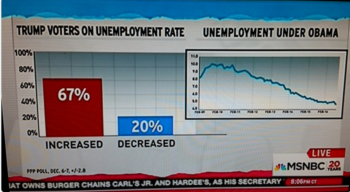

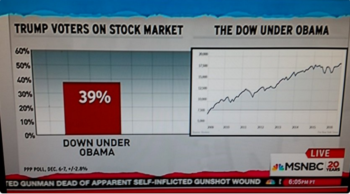

While it is difficult to quantify the effects of inaccurate or false information on individuals voting behavior, a poll released by the PPP on December 9 provides some rather startling findings that do support a voting bloc less informed than their peers. Among the results, Trump voters were far afield of the 50% who have a favorable rating of Obama (45% unfavorable) with a mere five percent holding a favorable view of the outgoing President versus a full 90 percent who see him in a negative light. More troubling were the false beliefs they held about his presidential legacy. Under Obama, the Dow has risen from 7,946 to 19,615 and unemployment has fallen from 7.8 to 4.6 percent. A majority of Americans are aware of both facts, but not Trump voters. Among them, 39 percent say the Dow has actually dropped under Obama and 67 percent believe unemployment has risen. On top of this, 40% of Trump voters believe their candidate won the popular vote, 60% believe millions voted illegally, 73% believe George Soros is paying protestors to take to the streets post-election, and an astounding 53% have inexplicably decided that California’s electorate should not count in the popular vote tally.

The reality of the contemporary crisis of democratic legitimacy is thus clear and yet the panic surrounding the “post-truth” America fails to acknowledge the long history of both manipulative political discourse and of radical ontological skepticism. The ability to spread false information has existed for as long as modern politics but has, ironically, risen precipitously in recent years, aided by the very tools that were supposed to provide the entire world with a free and readily available “fact-checking” sources. The foundation of the new skepticism also has deep roots whose seeds rose to prominence among social critics in the 1960s, building on ideas that go all the way back to Ancient Greece. One was Marshall McLuhan, an English professor in Toronto, who predicted the coming of an “electronic age” where retribalization would initiate a world dominated more by faith, mysticism, and mythology than science and reason. A few years later, the French Situationalist Guy Debord proclaimed the arrival of a Society of the Spectacle where all human ideas and emotions are commodified and sold back to the public in a representational field that was superimposed on top of reality. Below, I briefly consider their central arguments and relevance to examining our contemporary political malaise.

Marshall McLuhan was arguably one of the most brilliant cultural critiques of the 20th century, though his popularity in academic circles has waned in the years following his death. His seminal work, Understanding Media: The Extension of Man (1962), however, rather prodigiously predicted the world we live in today. McLuhan was the first to speak of the inchoate global village, imploding time and space through modern technology that radically alters our relationship to the social, economic, and political spheres, forcing us to choose sides in the key battles of the era (like the Civil Rights Movement). McLuhan was a technological determinist who believed that major social transformation was initiated by impactful new technologies, most profoundly the book, which commenced an age of scientific, technological, and economic advancement, before the more recent “electronic age,” which was pushing back toward the Zeitgeist of the oral tradition that preceded the “literate man.”

He argued this was accompanied by a change in consciousness that made the distant near and altered the very nature of our relationship to the world around us. Among the ways media specifically affected us was his famously misunderstood “the medium is the message,” which argued that the form of new media was substantially more important in determining its social effects than the content. To McLuhan, it didn’t much matter what you watched on television as much as the fact you were watching television at all. The reason was that particular technologies altered the nature of our sense ratios, focusing attention on some while neglecting others. McLuhan believed the electronic age, with the advent of radio, television, record players and the like, was replacing book culture and what he called the “literate man” with more tribal communities where consciousness itself became simulated and the time between action and reaction shrank to the point that there was little time for contemplation and critical thinking.

In his estimation, this change was moving society from a world of detached rationality and individuality to one punctuated by retribalization and mythology, where the individual becomes subservient to the larger social whole, undermining reason in lieu of group mythology. While many at the time pointed to the cultural revolution that soon ensued, many of his ideas were still relevant and they have only become more so in the digital/internet/smart phone world of today. Among the many prognostications that have come true are clear signs of retribalization occurring in contemporary Americans society today. Facebook and social media in general allow us to codify our friendships and business associations into well-defined groups. Specialized news outlets create political insularity where many are unwilling to even consider the arguments of their ideological foes and are often openly hostile to them. New virtual communities, based more on taste and predilection, have replaced proximity or old social lines of demarcation. At the same time, aging populations hold even more steadfastly to those old identity markers seemingly dispirited and alienated by the more diverse populations that now surround them. This has not been all bad, of course, but it has drawn ideological lines in the sand that have served the rise of right wing populism in both America and across Europe. The general decline in quality of life in the West dating back to the 1970s has been redefined in this discourse by a narrative that places white as victims of affirmative action, feminism, the liberal media, the liberal elite and, more recently, Muslims, PC culture, and immigrants. Trump played on all of these narratives at once, using white resentment as the foundation to spread misinformation and lies, largely immune to truth as the very institutions that could challenge those ideas have been disparaged as biased and thus untrustworthy. The end result is that mythology replaces science and reason as the defining founts of truth and echo chambers supplant balanced, reasoned, and civil debate.

From a more Marxist/postmodern perspective, Guy Debord took these ideas even further in his 1967 work The Society of the Spectacle. In the book, Debord argued we live in a world where representations of reality had replaced reality itself and relationships between humans had been largely replaced by relationships between humans and commodities. In this new configuration, commodities have colonized social life with social relationships between people mediated through images, leading to an impoverished quality of life and a lack of authenticity that distort human perceptions, degrade knowledge, and hinder critical thought. Debord believed the new channels of knowledge production were employed to assuage reality, with the spectacle obfuscating the past, imploding it with the future into an undifferentiated, never-ending present that disarms the channels for dissent and social transformation. The vast right wing news empire perfectly fits this description, cultivating a siege mentality that dehumanizes the many others, victimizing the power elites and treating all knowledge as a battleground of perception.

Many are indirectly aware of these theories as channeled through the work of the famous French philosopher Baudrillard in The Matrix Trilogy [5] or the translation of McLuhan’s worldview in David Cronenberg bizarre 1983 film Videodrome. Both provide a compelling visual metaphor of a world that is not lived as much as it is relived, with the average American spending countless hours daily surfing through the hyperreal miasma of popular and celebrity culture, the manufacturing of desire in the worlds of advertising and televisions and the shift to news as infotainment. For almost every social phenomenon, there is an almost endless array of narratives that describe both its contours and potential solutions, with a readymade shield to protect us from inconvenient truths that might challenge our deeply held shibboleths.

With McLuhan, Debord, and Baudrillard, we see three related theories on how reality has been distorted into subjective pods where an individual can live cocooned, comfortably oblivious of news or information that could shatter their worldview. The result has been a dramatic increase in political insularity that cuts off the channels for dialogue and debate, of conspiracy theories that distort real world problems and solutions, and a resultant deep cynicism, all working to undermine democracy and redefine the relationship of the public to our social and political institutions. Believing is seeing today, as the documentarian Errol Morris put it, with the average American more likely to see the world through their ideological beliefs as to alter those beliefs based on the empirical world around them. With the election of Trump, we have seen the culmination of these trends, as the thin line between truth and fiction disintegrates into an epistemological jungle where just about anything can be considered true. With a President Elect who finds little reason to adhere to traditional notions of truth, no problem is too big to be washed away in a tidal wave of half-truths, lies, and mythologies, altering the very contours of our reality and, in the process, the path of our collective future.

Image Credits:

1. The Scourge of Fake News

2. Total Facebook Engagements for Top 20 Election Stories from BuzzFeed News

3. Trump Voters on Who Won the Popular Vote (author’s screen grab)

4. Trump Voters on Unemployment Rate (author’s screen grab)

5. Trump Voters on Stock Market (author’s screen grab)

6. Still from David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983)

Please feel free to comment.

- Randall, Eric. “The ‘Death of Irony,” and Its Many Incarnations,” The Atlantic. September 9, 2011. [↩]

- See, for example, the NPR piece “A New ‘Post Racial’ Political Era in America” (All Things Considered, January 28, 2008), or Toure and Dyson, Michael Eric, Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness: What it Means to Be Black Now. New York: Atria Books, 2011. [↩]

- See Egan, Timothy, “The Post-Truth Presidency,” New York Times, November 4, 2016; Holland, Justin, “Welcome to Donald Trump’s Post-Fact America,” RollingStone, November 30, 2015; or Glasser, Susan, “Covering Politics in a ‘Post-Trust’ America,” Brooking Institute, December 2, 2016. [↩]

- Silverman, Craig, “This Analysis Shows How Fake Election News Stories Outperformed Real News On Facebook,” BuzzFeed News, 16 November 2016. [↩]

- See Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994. [↩]

I like your post-ironic/post-racial/post-fact alignment and the

McLuhan/Debord/Baudrillard review. I’m working on a paper now that addresses some of these same ideas from the perspective of materiality; the main question being the relationship between Baudrillard’s “simulation” and a New Materiality in reaction to the linguistic-cultural turn in the Social Sciences and Humanities of the 70s-90s. Can we speak of both material conditions in the recent election in conjunction with a brutal materiality (both literal and rhetorical) welded by Trump? As you say, “with a President Elect who finds little reason to adhere to traditional notions of truth, no problem is too big to be washed away in a tidal wave of half-truths, lies, and mythologies, altering the very contours of our reality and, in the process, the path of our collective future” — however, is there nothing to be done other than describe the phenomenon and bewail our collective failure? We all seem to be grasping at describing where we are. I’m almost fatalistic at this point.

Pingback: New 2016 Election Version of Clue: It was the Russians, in the Swing States with the Fake News! | The Fake News Effect

Pingback: Ebolanoia: Risiko i postfaktasamfunnet – Forskningsformidling