There Has Been Blood: Horror-Comic Masculinity in The Walking Dead

David Greven / University of South Carolina

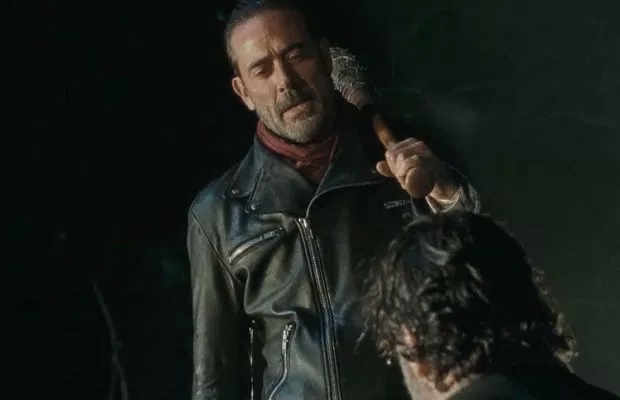

The sense of grief and bewilderment many Americans have been feeling in the wake of the 2016 Presidential election and Donald Trump’s emergence as President-Elect was oddly prefigured by reactions to the premiere episode of The Walking Dead’s (AMC, 2010-present) (TWD) current and seventh season, “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be.” The sixth season ended with a cliffhanger: the protagonists led by Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) are terrorized by Neegan (Jeffrey Dean Morgan), the leader of the nefarious Saviors, who wields a barbed-wire-covered baseball bat named “Lucille.” Prone to fanciful speech evocative of the elementary schoolyard (“pee-pee pants”), Neegan plays a game of “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe” to decide which head of his kneeling captives to bash in. Knowledge of Neegan’s victim was withheld for the premiere, much to the vocal ire of fans. Neegan’s victim turns out to be the red-headed former military man Abraham (Michael Cudlitz). Known for his colorful cussing, Abraham spits out a defiant “Suck my nuts” after Neegan’s first blow. Killing off Abraham seemed like something of a safe choice, since he was not one of the original cast members. But then, after the renegade biker-tough-guy-with-a-heart-of-gold Darryl (Norman Reedus) attempts to strike back at the enemy, Neegan kills the beloved Glenn (Steven Yeun), an expectant father and one of the original cast members, as his wife Maggie (Lauren Cohan) looks on in indescribable horror. Glenn’s horrific death in the premiere — taken directly from the comic book series that inspired the television show — shocked and enraged both longtime viewers and commentators alike.

What was it about this episode that drew such fire, given the depressing, grim, and often graphically violent nature of this series, surely one of the most downbeat ever to air on television? Many complained about the graphic violence here as evidence that the series had finally gone too far, that television itself had gone too far. Other intensely violent scenes in the series’ history did not attract ire — for example, the nearly murderous fight scene between Michonne (Danai Gurira) and the main season three villain The Governor (David Morrissey), involving head-smashings and Michonne’s blinding of the Governor; the season four finale in which Rick, Michonne, Daryl, and Rick’s son Carl (Chandler Riggs) dispatch a gang holding them hostage, one of whom attempts to rape Carl, a brawl that climaxes in Rick biting into the neck of one of the gang members; the mass-killing in the Alexandria Safe Zone, led by the former Ohio congresswoman Deanna Monroe (Tovah Feldshuh), when the psychotic Wolves descend on Rick’s group and its allies.

An excellent critic, Matt Zoller Seitz, who has always been somewhat critical of the series, condemned the premiere’s “empty violence.” Comparing it unfavorably to the HBO medieval fantasy series Game of Thrones’ “Red Wedding” episode, Seitz faulted TWD’s premiere for focusing on the preening and taunting Neegan and his sadism; he also likened the show’s methods to “a bat to the head. Whunk! Whunk! Whunk! Splat! Goooosh!” Brandon Katz, writing in Forbes, offers a similar critique couched in an analysis of the show’s declining ratings.

If the sixth season left one’s faith in the series a bit shaken, “The Day Will Come When You Won’t Be” provided ample evidence of the show’s enduring relevance. This relevance once again proves to be the series’ depiction of American masculinity as a series of performance styles, a knowing and shifting masquerade. This is not to say that strong women characters have not been a crucial part of the series’ success — I would cite Carol (the great Melissa McBride), Michonne, and the too-short-lived congresswoman Deanna Monroe as stand-out examples. But TWD has been most significant as a critique of American masculinity that eerily evokes historical images and constructions of American manhood while offering insights into masculinity’s contemporary crisis-mode — what could be more relevant? “The Day Will Come,” for all of its obvious machinery, continues this pattern of incisive critique.

Neither of Neegan’s victims in “The Day Will Come” is typed as gay; indeed, Glenn is expecting a child with his wife Maggie, Abraham has moved from an affair with Rosita (Christian Serratos) to one with Sasha (Sonequa Martin-Green). Yet there is ample queer subtext here in Neegan’s scary-funny characterization and his obsession with Rick, whom he seeks to humiliate, subjugate, and possess. Neegan, I argue, is the fulfillment of several years of over-the-top masculinity originating in the outrageous, transgressive teen gross-out comedies that peppered the late 1990s, most notably the American Pie films and their ilk, and extending to horror. Neegan recalls the anarchic, foul-mouthed, sexually provocative Stifler (Seann William Scott) in American Pie (Paul Weitz and Chris Weitz, 1999) and its sequels. Just as Stiffler torments the upstanding and reserved members of the male group that maintain an uneasy relationship with him, so, too, does Neegan harass Rick. This rivalry draws on the comic archetype of The Yankee versus the Backwoodsman, the effete intellectual versus the gleefully uncouth mountain man. The historical precedent for these male relationships is the cheerfully sadistic Brom Bones’ persecution of the solitary pedagogue Ichabod Crane in Washington Irving’s famous 1820 tale “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

The scatological aspects of the late-90s teen comedies echo in Neegan’s language and antics, often both sophomore and sadistic at once. The 90s teen comedies ceded to the Beta Male comedies of the Judd Apatow school, which skewed older; the focus shifted to hapless twenty- and thirty-somethings who seemed left out by society yet, in their own sluggish and slapdash way, remained heroic. Neegan fuses these millennial and post-millennial modes of wayward masculinity—the arrested development of the teen comedies, the amusing anomie of the Beta Male—with the emergent, aggressive image of the white working-class male associated at present with the alt-right movement. Neegan’s grandiose narcissism, desire to intimidate, and especially his explicit misogyny align him with constructions of alt-right white males whose descriptions of the kind of woman they despise is best summed up in the phrase “basic bitch.”

Another aspect of TWD this season that resonates with trends extending from the 90s teen comedy to the Beta Male comedy and the bromance is a relentless gay-baiting. Homoerotic homophobia informs Neegan’s persecution and humbling of Rick, threats to and taunts about Rick’s manhood. For example, in the seventh season episode “Service,” Neegan and his crew arrive at the Alexandria Safe Zone earlier than planned, demanding the goods owed them and perusing the compound, taking what they please and intimidating the residents at will. Neegan stands so physically close to Rick that each man must have intimate knowledge of the other’s olfactory nature, and he informs Rick that he has “slipped my dick down your throat and you thanked me for it.” Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s devilishly comic performance intensifies the threatening homoeroticism in Neegan’s persona.

In my previous Flow essay on the series, “The Walking Straight,” published at the start of the series’ second season, I critiqued the show for failing to include or imagine a gay/lesbian/queer presence on the series. TWD has certainly delivered on that front, now boasting several queer characters, including regular cast member Aaron (the wonderful Ross Marquand), part of a gay male couple in Alexandria, and Tara (Alanna Masterson), whose girlfriend Denise (Merritt Wever), a nervous physician slowly coming into her own, was controversially killed last season, joining several other prematurely killed-off TV lesbian characters. (No trans character has yet been introduced, however.) While a discrete study of the series’ queer characters, their treatment and what they bring to the narrative, is needed, I believe that TWD is to be commended for including a visible queer element. And characters such as Daryl, Morgan, Father Gabriel (Seth Gilliam) and others, including Carol (who specifically refutes one character’s assumption that she’s a lesbian), remain suggestively ambiguous in terms of their sexuality.

With the inclusion of the scary-funny Neegan, TWD continues its exploration of the styles of masculine performance, the inability to sustain a coherent performance of masculinity. The allegory of our current political situation in the seventh season premiere episode is unmistakable. The horror clown Neegan pulverizes two characters who represent the stakes of Trump-era politics, the angry white working class male (Abraham) and, among the gentlest of the group, the non-white male (Glenn). Neegan later stages a faux-Abraham and Isaac tableau by making Rick chop off his son Carl’s arm, only to stay the distraught father’s hand at the last possible moment. This is masculinity as a horror comedy, with Neegan as Lacan’s obscene father, toying with his minions and keeping the spoils for himself. TWD has not yet lost its relevance.

Image Credits:

1. Walking Dead Premier

2. Neegan

3. Stifler and Apatow Men

4. Queer Representation: Aaron and Tara

Please feel free to comment.