TV Finales: Rethinking the Cliffhanger

Casey McCormick / McGill University

Tune in next week! To be continued. Next time on…

Anticipation is built into TV’s economic and formal structures. Keeping viewers invested in a storyworld goes hand in hand with maintaining ratings and enticing advertisers. Season finales are at the core of this ethos – they generate extra levels of hype, which usually translates into larger viewership. Furthermore, season finales produce the conditions for heightened anticipation during a show’s hiatus. With an increasingly competitive TV marketplace, gaps between episodes and seasons often involve a slow drip of paratextual information [1] from producers and fans, such as teaser images, promos, interviews, trailers, and spoilers, all designed to optimize anticipation. In short, the economic imperatives of the TV industry dictate that season finales must thrive on the ability to perpetuate narrative interest – not satisfy it. [2]

When I sat down to watch “Last Day on Earth,” The Walking Dead‘s sixth season finale, the day after its initial airing, I knew that it would end on a cliffhanger. I’d opened Facebook and Twitter and had seen no “RIP _____” posts, no crying emoji next to a character’s name, and no vague headlines with ominous photos. In this case, the lack of spoilers was the spoiler. So I was not at all surprised when Negan, the newly arrived villain, raised his barbed-wire baseball bat, and the camera switched to an unknown POV, then faded to black as the mystery victim suffered a brutal beating.

Like many other season-ending cliffhangers in TV history, this episode spawned anger, frustration, and a whole lot of anticipation. Despite the fact that viewers overwhelmingly hated “Last Day on Earth,” anger has not prevented them from engaging in diverse methods of “forensic fandom.” Dozens of recaps, shot-by-shot visual analyses, and audio dissections of the scene, as well as websites compiling production information and videos analyzing promotional materials, are dedicated to answering one question: Who did Negan kill? By the time you read this article, we will all know the answer. But I’m not so much interested in the answer as I am in how this cliffhanger seemed to fail on the level of narrative but was so successful on the level of hype. “Last Day on Earth” demonstrates the significance of TV finales, particularly in a traditional (i.e. incremental) TV distribution model. [3]

As key sites of anticipation, finales are essential to how we structure our experiences of televisual storytelling. [4] Even before the prevalence of complex serial TV, finales have stood apart from other episodes in a season; the expectation of higher ratings places pressure on shows to offer something special to their audiences. For sitcoms and procedural shows, that might mean a notable guest star, a big event like a wedding or graduation, or the departure of a main character. For serial dramas, it usually means a major confrontation between opposing forces and some kind of game-changing revelation. [5] In some cases, that revelation leads to a cliffhanger, a dire moment that distills narrative momentum into a single question: Who…? How…? Why…?

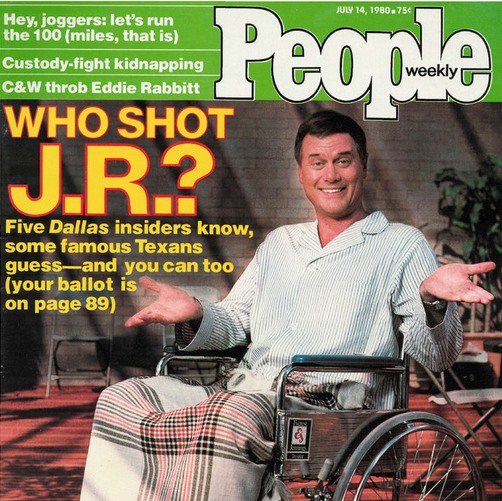

In “A House Divided,” Dallas’s famous season three cliffhanger, the question of “who shot JR?” gave audiences a mystery to solve; they could consider each character’s motivations and build a case based on narrative evidence. Meanwhile, the Negan cliffhanger does not leave us with a question that we can logically parse out – the apparent randomness of Negan’s brutality is, in fact, the point of the character, and one of the key themes of TWD. While even a literal “cliff-hanger” leaves some room for audiences to consider the strengths of a character in peril and the specificities of the situation in an attempt to calculate said character’s odds of survival, TWD gave us a cliffhanger with no narratively motivated mystery to ponder: it’s pure anticipation for the sake of anticipation.

The failure of this cliffhanger is compounded by other problems with TWD’s season six storytelling. Before the season began, viewers knew that Negan would arrive in the finale. Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s casting as the infamous villain was announced in November 2015, confirming the character’s debut as the telos of the season. Red herrings and circuitous plotting throughout the first 15 episodes resulted in frustration for many viewers, but the promise of Negan and his iconic baseball bat kept us on the hook. The fact that Negan’s arrival was common knowledge meant that, come finale time, the climactic scene contained no real “revelation” or new information to process. In addition, TWD is known for featuring significant deaths in its season (and mid-season) finales, so the cliffhanger betrayed the series’ established logic of storytelling flow. One reading of the final scene would be that when Negan turns his bat on the viewer, he is punishing audiences for their obsession with spoilery moments, perhaps suggesting that some modes of fandom miss the point. But as many viewers have noted, the effect of the scene was not the feeling of shock and excitement that Kirkman claims as the goal, but rather of anger and resentment: “fucking cliffhangers, man.”

The cliffhanger has an inconsistent reputation – on the one hand, it is considered a cheap trick and is historically tied to the economic motivations of serial storytelling, enticing consumers to buy more narrative. [6] On the other hand, the cliffhanger is a signature element of many “quality” TV series, deploying seriality in the service of narrative complexity. Cliffhangers done right are excellent vehicles for active fandom; they encourage viewers to engage with storyworlds through discussion, debate, and close reading. But “Last Day on Earth” manufactures a “water cooler” topic that necessarily removes fans from the storyworld: the best evidence to build a case for any particular victim would have to come solely from the paratextual realm, based on an actor’s recent haircut, fan favoritism, or adaptation politics. As a lover of storytelling, I see this kind of cliffhanger as a narrative failure; but there’s no denying that it generated an intense response that has resonated through popular media and will likely be converted into financial gains for AMC.

So maybe calling “Last Day on Earth” a failure is unfair and inaccurate. TV experience has always been defined by the intermingling of textual and paratextual signifiers, and the feedback loop between producers and consumers is more transparent than ever thanks to social media. The response to this cliffhanger is indicative of how active fans transcend narrative boundaries, and how the process of production becomes part of the story. But it also reveals the continued pressure on cable and broadcast networks to sacrifice storytelling merit on the altar of ratings. [UPDATE: AMC just released a 3-minute “sneak peek” of the season seven premiere. With 2.5 million views in less than 48 hours, this crucial scene placed out of context once again prioritizes hype at the story’s expense.]

In Volume 23, Issue 3, I’ll discuss the unique circumstances of series finales and explain our love/hate relationship with narrative closure. Stay tuned!

Image Credits:

1. Lost in Space, “The Reluctant Stowaway” (1965)

2. AMC promotion for the Season 6 finale of The Walking Dead

3. The Walking Dead “Last Day on Earth” (2016)

4. Despite similarities in their patterns of hype, “Who did Negan kill?” is the inverse of “Who Shot JR?”

5. Author’s screen grab

- My work on paratexts here and elsewhere builds on Jonathan Gray’s Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and other Media Paratexts. New York: NYU Press, 2010. [↩]

- Jason Mittell writes that “the [American TV] industry equates success with an infinite middle and relegates endings to failures” (321). Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York: NYU Press, 2015. I am indebted to this book’s chapter on series finales. [↩]

- In a simultaneous distribution model (like that of Netflix original series), finales take on different characteristics. [↩]

- In Complex TV, Mittell reserves the term “finale” for what he considers a series’ “conclusion with a going-away party” (pg 322). I use “finale” in a more general sense, as I argue that season and series finales throughout history and across genres share similar narrative toolkits. [↩]

- Greg Smith, “Caught between Cliffhanger and Closure: Potential Cancellation and the TV Season Ending” (paper presented at the Society for Cinema & Media Studies conference, 2011). [↩]

- Jennifer Hayward, Consuming Pleasures: Active Audiences and Serial Fictions from Dickens to Soap Opera. Lexington: U P of Kentucky, 1997. [↩]

Thank you for sharing such an intriguing, timely column! I was especially interested in your connection between TWD’s cliffhangers and their response to forensic fandom: “One reading of the final scene would be that when Negan turns his bat on the viewer, he is punishing audiences for their obsession with spoilery moments, perhaps suggesting that some modes of fandom miss the point.” It’s becoming increasingly difficult for these tent pole shows (TWD, GoT, etc.) to maintain any kind of secrecy during and especially between seasons. Those frustrations are often born out in producer and showrunner interviews, litigious confidentiality clauses, etc.

However, it’s interesting to consider those frustrations manifesting in the text as direct address to active fans. Despite the refrain of improving relations between producers and fans, this reading reminds me somewhat of SPN’s initial derision and address of fans in “The Monster at the End of This Book” and “The Real Ghostbusters” (2009). These responses are, by many standards, a denunciation of this mode of fan engagement. That being said, ancillary content such as Talking Dead implies an industrial awareness of the importance of their dedicated fan base.

As you note, “The response to this cliffhanger is indicative of how active fans transcend narrative boundaries, and how the process of production becomes part of the story.” Fans are clearly embracing the process of production as part of the story but do you believe producers are as willing to loosen the reigns and embrace this mode of engagement?

Thanks for your comment, Lesley! I think it’s clear that producers want fans to *think* they’re embracing this collaborative mode of engagement, but likely in many or most cases it’s not totally true. But in a way, it doesn’t really matter if producers genuinely embrace this model or not–it’s the lived experiences of these stories that matter, so if fans *feel* they are impacting the story, then for all intents and purposes, they are.

Of course, there are many accounts of policing fandom, and this policing sometimes has troubling implications. It’s important to look at individual cases, and with this example from TWD, it appears that the “punishment” of the spoiler-driven fan only exacerbated spoiler-focused forensic fandom during the hiatus. So one thing was happening on a formal level, but paratextual engagement overshadowed that meaning. Would you agree? What do you think about this shifting balance of narrative impact?

This column and the previous comments have got me thinking about how fans don’t just go to the “paratextual realm” to look for spoilers, they also use paratextual events or objects to justify narrative decisions (and I’ll admit that I find this disconcerting). What I mean is how once TWD aired and people knew who was killed, they used the comic storyline as justification for the necessity of that narrative decision, in response to criticism of the racial politics of killing off another POC. I’m also thinking of the death of Lexa in The 100 since I seem to remember that it was justified by some people because the actor was cast in another show.

I don’t actually watch either of these shows, so I might be getting the specifics wrong.

Yes, thank you for writing this! The evolution of cliffhanger mystery-solving from the use of textual to paratextual clues is so much less interesting narratively speaking. For better or in this case probably worse, I wonder how much it actually decreases the viewer’s connection to the characters and narrative. In what ways do you think the shared anger and resentment and “water cooler” gossip generated by this hype and storytelling is increasing emotional connections to and engagement with the television experience?

Pingback: the electric present

Pingback: TV Finales: On-Demand Endings Casey McCormick / McGill University – Flow